A Warners reissue puts the cream of American gangster epics within easy reach, and at a better price. Robinson, Cagney and Bogart each found stardom in crime, just before the Production Code banned the genre outright. The four-disc set tells the rags-to-riches-to-gutter tales of Cesare Rico Bandello, Tom Powers, Duke Mantee and Cody Jarrett. That quartet of thieves, thugs and killers caught the imagination of the American public — glamorizing the ‘flip side’ of the American Success Story. The high-def remasters are also restorations, which for the earliest pictures are true revelations.

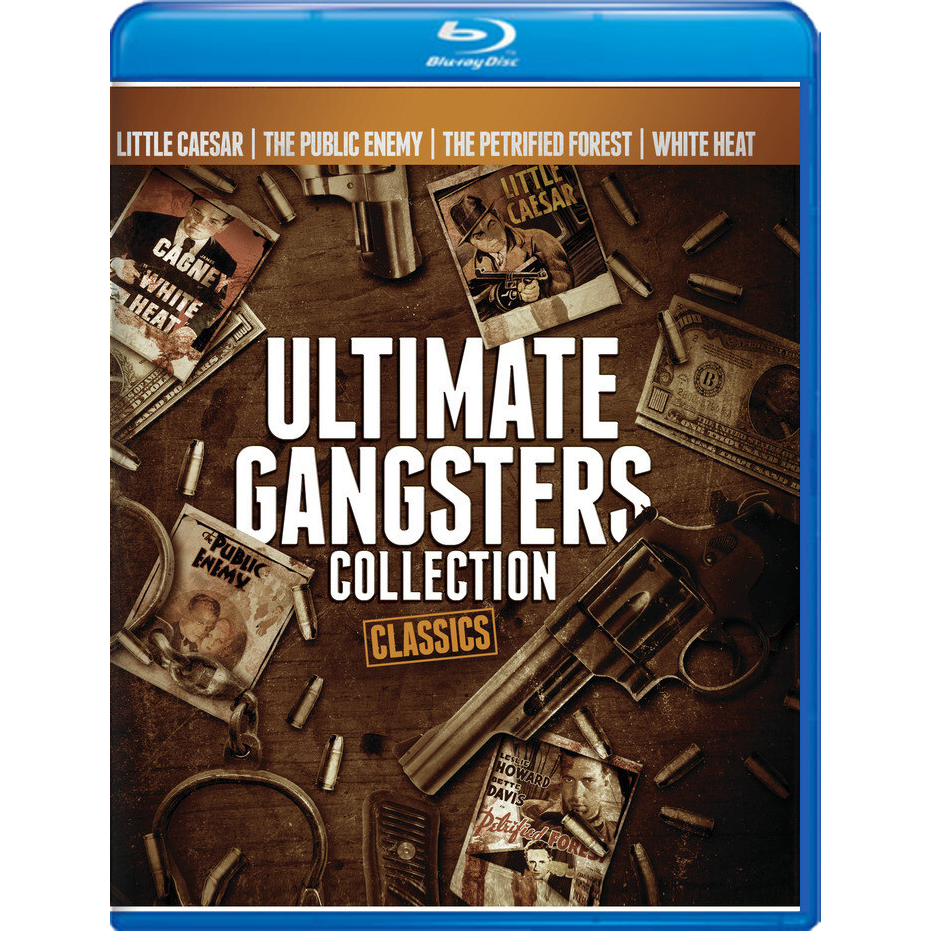

Ultimate Gangsters Collection: Classics

Little Caesar, The Public Enemy,

The Petrified Forest, White Heat

Blu-ray

Warner Bros.

1930-1949 / B&W / 1:37 Academy / 358 min. / Street Date June 24, 2025 / Available from Moviezyng / 29.98

Starring: Edward G. Robinson, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Glenda Farrell; James Cagney, Edward Woods, Jean Harlow, Joan Blondell, Beryl Mercer, Donald Cook, Mae Clarke; Leslie Howard, Bette Davis, Humphrey Bogart, Genevieve Tobin, Dick Foran, Joe Sawyer, Porter Hall, Charley Grapewin.

Cinematography: Tony Gaudio; Devereaux Jennings; Sol Polito; Sid Hickox

Composer: none; none; none; Max Steiner

Written by Francis Edward Faragoh, Robert N. Lee, Robert Lord from the novel by W.R. Burnett; Harvey Thew from the story Beer and Blood by Kubec Glasmon & John Bright; Charles Kenyon, Delmer Daves from the play by Robert E. Sherwood; Ivan Goff, Ben Roberts story by Virginia Kellogg

Produced by Hal B. Wallis; Darryl F. Zanuck; ?; Louis F. Edelman

Directed by Mervyn LeRoy; William A. Wellman; Archie L. Mayo; Raoul Walsh

Warner Bros. waited a few years before committing to the DVD format, but when they began rolling out the discs around 2005, their library of quote ‘timeless classics’ unquote seemed bottomless. In 2013 they offered their first Blu-ray collector’s set featuring four key gangster spectacles, the Ultimate Gangsters Collection: Classics. Thanks to some 21st century restorations, Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart now look far better in HD. One feature is both rejuvenated and has had some cut material reinstated.

Warner Bros. waited a few years before committing to the DVD format, but when they began rolling out the discs around 2005, their library of quote ‘timeless classics’ unquote seemed bottomless. In 2013 they offered their first Blu-ray collector’s set featuring four key gangster spectacles, the Ultimate Gangsters Collection: Classics. Thanks to some 21st century restorations, Edward G. Robinson, James Cagney and Humphrey Bogart now look far better in HD. One feature is both rejuvenated and has had some cut material reinstated.

The original Warners gangster pictures are still fascinating. They launched the genre into the talkie era and remain a dynamic reflection of social unrest during the Great Depression. The disparity between the rich and the poor reached absurd extremes, with a third of the workforce idle as the rich indulged ever-greater luxuries. The selfish screen bandits that took what they wanted enjoyed an alarming public appeal. They served as a warning of how society could crumble, yet also allowed have-nots to indulge fantasies of conspicuous success.

The majority of today’s kids have had little if any contact with these great pictures, which are still packed with dangerous ideas, alarming violence and high drama. So show one to a kid today!

Thanks to film restoration efforts 1930’s Little Caesar now looks far more modern than did the murky, hard-to-hear 16mm prints we once watched on TV. There had been popular silent gangster films, including a couple by of classics by Josef von Sternberg. But the realism of writer W.R. Burnett struck a nerve, making Edward G. Robinson into a huge star. His final dialogue line became one of the earliest ‘unforgettable’ bits of talkie history: “Mother of Mercy, is this the end of Rico?”

The story sets the formula for a hoodlum’s rise and fall. Stick-up man Cesare Enrico Bandello (Edward G. Robinson) and his best friend Joe Massara (Douglas Fairbanks Jr.) find positions in the gang of Sam Vettori (Stanley Fields). Rico eventually becomes boss, going especially hard on ‘yellow’ gang members. Teaming up with Big Boy (Sidney Blackmer), they pull off robberies and create havoc. Police Sgt. Tom Flaherty (Thomas E. Jackson) must wait for his chance to end Rico’s career. It comes when Joe falls in love with his dancing partner Olga Strassoff (Glenda Farrell). He loses his nerve and wants to turn State’s Evidence. Rico arrives to murder yet another squealer, but for the first time can’t go through with it.

Little Caesar establishes the template for every urban gangland bio to come. Rico has ambition and drive but little judgment. He fastidiously avoids drink but cannot resist the temptation of power. Whether it be taking over his little gang or hurrying to rub out a squealer, Rico’s every move shares an impatient, urgent quality. The story tempo is faster than the typical talkie of the day, when sound recording had barely cleared the ‘talk into the bush’ stage.

Rico succumbs to a classic gangster flaw — a streak of human feeling that betrays his credo of absolute ruthlessness. When survival depends on killing his old pal Joe Massara, he can’t do it. Little Caesar shows its pre-Code willingness to be adult by hinting that Rico may have an unacknowledged attraction to Joe, the stick-up criminal who (rather unlikely) is also a cultured, refined exhibition dancer. When Rico objects to Joe’s romance, we suspect that the reason is jealousy.

Some silent gangster protagonists were depicted as chivalrous heroes, that redeemed themselves through a noble sacrifice — going to prison or confessing so that some more deserving buddy can get the girl. Rico Bandello is as nasty on the way down as he was going up, and so cocky that the crafty Sgt. Flaherty can easily goad him into showing himself. His dishonorable demise introduces the concept of ‘death in the gutter,’ overseen by a poster of the lovers who are now free (at least we hope so, as they didn’t make any immunity deal). Rico wails ‘Mother of Mercy’ and goes out like the rat he is. Note: We’ve read that the famous dialogue line is actually a censored redub of “Mother of God,” but in the film we can see, Rico’s lips seem to say “Mercy.”

Mervyn Leroy’s direction is somewhat static yet tells the story well, pointing out important details like the fancy jewelry that so impresses Rico. Edward G. Robinson must carry much of the show as few of the other actors seem particularly comfortable, especially the miscast Douglas Fairbanks, Jr.. Glenda Farrell hasn’t yet hit her wisecracking pace and doesn’t draw much attention. Still playing to the Vitaphone microphones, actors Thomas E. Jackson and Stanley Fields seem concerned with enunciating their lines clearly.

This iteration of Little Caesar looks great — especially if one has only seen older copies in marginal condition. We were always told not to expect anything better, that good film elements no longer existed.

Each of the titles in this collection carries a Leonard Maltin- hosted introduction that precedes a “night at the movies” slate of short subjects. A feature trailer is included for each title as well. Little Caesar’s “night at the movies” extras include a trailer ( Five Star Final), the brain-altering Merrie Melodie cartoon Lady Play Your Mandolin and a lame but amusing dramatic short with Spencer Tracy, The Hard Guy. On the academic side of things is a commentary by the knowledgeable Richard B. Jewell, and the featurette End of Rico, Beginning of the Antihero, which gathers a number of authors of genre criticism. There’s also a censor-mandated text crawl that preceded the film’s 1954 reissue. Twenty years later, the Production Code was still worried about gangsters corrupting the youth of America.

Released not long after Little Caesar, The Public Enemy shows advances in direction, storytelling technique and acting. The emerging Warner house style is more evident. This time the ‘rise and fall’ story arc begins in childhood, showing how its hoodlum hero was partly formed by societal conditions, namely, the corrupting influence of the saloon trade.

In pre-Prohibition days Chicago is one huge booze town. Boyhood delinquents Tom Powers and Matt Doyle (James Cagney and Edward Woods) soon become hired thugs for a string of bosses and bootleggers. As they move up in the crime world they acquire fancy clothes and cars, and fast women like Mamie (Joan Blondell), Kitty (Mae Clark) and Gwen Allen (Jean Harlow). Tom stays in touch with his uncomprehending mother and his disapproving brother. He always figures he’s tough enough to buck whatever comes along, even a gang war that doesn’t go favorably for his side.

Environmental factors are stressed as the source of crime, a socially conscious theme that became the cornerstone of Warners’ ’30s outlook. Tom Powers and Matt Doyle spend over a reel as slum kids in the employ of the local fence, Putty Nose (Murray Kinnell). Tom’s stern father, a policeman, beats him regularly. All we see on the boy’s face is the desire to strike back at the world.

By the time Tom Powers is portrayed by the magnetic actor James Cagney, he’s a budding sociopath who doesn’t give a damn what happens to the victims of his crimes. When prohibition hits Tom uses thug tactics to peddle one gang’s brand of beer. The classic scene where Cagney roughs up a speakeasy owner, spits in his face and lets the competitor’s beer run on the floor is the perfect distillation of cutthroat business practices in action. Thirty-six years later, George Segal and Roger Corman copied the scene for The St. Valentine’s Day Massacre. They couldn’t improve on director William Wellman’s original.

James Cagney is surrouned by good performers but would be sensational all on his own. Every scene billboards Tom’s street-smart style. He makes sly faces at people, does little punching motions (even at his own clueless mother) and the occasional dance-like pirouette, when entering cars or jumping out of trucks. We can’t take our eyes off Cagney, as he’s just so much more ‘real’ than anyone else. The bluenoses must have turned purple to see how Cagney made snide arrogance look so attractive. We’re invited to cheer Tom when he mocks a gay tailor. Basic rules of civilized behavior go out the window when he socks Mae Clarke in the face with a grapefruit.

Tough guy Tom Powers doesn’t know his own limitations. He’s constantly being cheated by his bosses but never thinks to ‘take over’ as did Rico Bandello. The classier grade of moll represented by Jean Harlow makes him feel sexually insecure. An accident with a horse leads to a bizarre rubout, a revenge echoed much later with a horse’s head in The Godfather. The script avoids direct gunplay. But Tom takes the murder of his best buddy — an slaying carried out with Army-issue machine guns — as a cue to single-handedly charge into a den of enemies. His act of bravado doesn’t work out quite as he hopes.

Director William Wellman’s restrained staging makes the most of the ending, which plays like something out of Edgar Allan Poe. Wellman cannily sets us up by showing Tom’s mother happily changing the bed sheets in preparation for her boy coming home. Tom has already admitted to himself that he ‘ain’t so tough’ and is perhaps genuinely ready to reform. It’s a shocking, uncompromised finale for one of the best movies of the ‘thirties.

Jean Harlow’s performance is almost entirely her zowie looks, as she barely gets through her coached dialogue. Edward Woods is good as Tom’s buddy and Joan Blondell makes a winning impression as a gangster’s wife. Mae Clark’s bimbo moll has been the butt of grapefruit jokes ever since. We believe that Cagney socked her for real, as she seems truly surprised. Some books claim that a real marksman with a loaded Thompson submachine gun was used for rub-out a scene with Cagney and Woods. But the famous photo of that setup is probably just that – a setup.

The picture quality of The Public Enemy is a true revelation. Around the turn of century Warners lucked on to a forgotten, surviving good element for the film. The title had been reissued and printed so many times that the standard elements must have been bad dupes of dupes. Television copies and even archival prints were simply terrible – blurry and mis-framed, with scratchy audio. A few moments revert to poorer quality but at least 95% of the presentation looks pristine, like it was filmed yesterday. We can even see that James Cagney appears to wear lipstick and eye shadow makeup.

Leonard Maltin is back to introduce more vault goodies. The Eyes Have It is an early Edgar Bergen-Charlie comedy short and Smile, Darn Ya is another surreal cartoon set to a quirky pop tune of the day. The commentary this time is by Robert Sklar, who also appears in the featurette Beer and Blood: Enemies of the Public along with a particularly entertaining Martin Scorsese and Alain Silver. We see a vintage newsreel and a trailer for another Cagney film, Blonde Crazy. And whatever you do, don’t pass up the 1954 censor text scroll.

Not every thrill-seeking gangster fan appreciates The Petrified Forest, a talkfest that spends more time on philosophical poetics than gritty action. But it introduced Humphrey Bogart as potential star material and is a masterful example of a stage play adapted to the screen. It’s at least as effective as Key Largo, which in retrospect plays like a postwar remake. And it features Bette Davis in a major role, upping the interest for film fans in general.

As might be expected of a stage adaptation, the action of The Petrified Forest is limited to one location. The Black Mesa Café in the Arizona desert greets a series of unusual guests one hot afternoon. Owner Jason Maple (Porter Hall) goes off to a meeting. His daughter Gabby (Bette Davis) dreams of escaping to France, but must instead fend off the advances of the gas pump boy, football player Boze (Dick Foran). Then a vagabond walks in off the desert. He’s the writer & poet Alan Squier (Leslie Howard). Having thumbed his way across America, Alan now gives Gabby a hint of more exciting things in life. They say their farewells when he leaves, but Alan soon returns along with some other ‘guests’ … all held at the gunpoint of a gang of rural stickup men. Their leader is the notorious escaped killer Duke Mantee (Humphrey Bogart).

Self-styled intellectual Alan claims not to be English. We’re told that Humphrey Bogart’s Mantee affected the same dress and some of the mannerisms of the famous bank robber John Dillinger, and playwright Robert E. Sherwood highlights a meeting of minds between hoodlum and poet. Sherwood also scores some unflattering points about American attitudes. The wife of a banker turns virtuous under the siege; the pushy football player makes a dumb try at heroism, and the old codger (Charley Grapewin at his best) takes a liking to Duke Mantee because he has fond memories of Billy the Kid! In a disturbing detail, Bette Davis’ father belongs to a uniformed paramilitary group called The Black Horse Troopers. In a rare choice for movies of the day, Sherwood reserves good dialogue exchanges for two black characters, an outlaw and a chauffeur.

Leslie Howard rattles on poetically about fate and courage. It’s easy to see why both Bette Davis’ Gabby and the female public at large adored this fantasy Englishman, a type not likely to be found in real life. Liquor helps both Squier and Mantee bring their feelings out in the open. Mantee is a lost soul working his way toward an inevitable violent death. Squier considers himself a kindred spirit, with a similar grave in his own future. Because he wants to nurture his Death Wish and save the other hostages, Alan asks Mantee to shoot him on his way out the door … pumping some poetic irony into the proceedings. It’s the kind of stylized drama in which average-looking people make stylized speeches about abstract concepts. Howard’s poet blabs a lot, while Bogart’s Mantee communicates his feelings in a few terse statements.

Many viewers think gangsters belong in the city, but anybody with a gang qualifies, even The Wild Bunch, a western that borrows potent gangster themes. Charley Grapewin’s old coot makes a cogent remark about Mantee being ‘American,’ a homegrown menace instead of one of those despised foreign immigrants in the cities. The urban gangsters come from ghettos and are ambitious practitioners of the American way of business, skipping all the rules. Rural bandits like Pretty Boy Floyd are the disillusioned product of the Depression, born of the dustbowl. In the imagination of some artists, they strike back against society to protest economic oppression.

This is a good Bette Davis performance; she seems enlivened playing opposite a worthwhile leading man. In his own way Bogart is another step toward modern screen acting. His imposing presence and craggy face do much of the work; instead of actively emoting he inhabits the character and lets his eyes carry his intent. The opening shots of Bogart walking with his arms in an apelike posture are a bit thick, but beyond that, we have no complaints.

For 1936, this is an extremely fluid and imaginative staging of what is basically a one-room play. Archie Mayo’s name doesn’t come up in any lists of great directors but he hit the nail on the head this time.

The Petrified Forest is again a nicely scrubbed restoration. The studio look of the time didn’t go in for deep blacks, which in this case gives the stagey sets a dusty quality. The sound has been particularly improved from old 16mm TV prints — the movie no longer plays like a fossil.

We soon because accustomed to DVD extras that convene selected experts to talk on camera — and then edit what they have to say into short bites. This featurette is called Menace in the Desert. The commentary is by Bogart biographer Eric Lax. Another extra is an entire 1940 radio adaptation with Bogart, Tyrone Power and Joan Bennett.

Leonard Maltin’s string of short subjects includes a newsreel, a grating musical short Rhythmitis, the cartoon Coo Coo Nut Grove and a trailer for Bullets or Ballots.

Thirteen years later, the entire world has been transformed by the experience of World War II. A major gangster epic re-introduced James Cagney to the genre, with a combination of speed and fury that was positively dizzying. Raoul Walsh’s amazing thriller White Heat expands the genre in all directions. Although technically a rural bandit, James Cagney’s Cody Jarrett is a bigger-than-life criminal mastermind who would give Batman pause. The complex film noir character seems to embody all of the out-of-control elements of the postwar years. And he’s a raving psycho to boot.

The movie begins in furious action. Psychopath Cody Jarrett (James Cagney) and his gang rob a train, coldly executing four railroad employees. They hole up in a mountain cabin with Cody’s Ma (Margaret Wycherly), who is also the gang’s main strategist. Ma also ministers to her son’s frequent mental seizures. Cody decides sidesteps a likely murder rap by confessing to a robbery in another state that he arranged to happen at the same time. Aware of Jarrett’s tricks, T-Man Phil Evans (John Archer) connives to put a spy in his prison cell, agent Hank Fallon (Edmond O’Brien).

Cody’s gang stays together, but the disloyal lieutenant Big Ed (Steve Cochran) moves in on Cody’s wife Verna (Virginia Mayo). Even the watchful Ma can’t stop this betrayal. Meanwhile, Evans and Fallon’s confidence game in the prison block seems to be working — until Cody breaks down under a severe psychotic episode. Neither T-Man is prepared when Cody uses a fake seizure to effect a prison escape — and takes Fallon along with him on a new spree of violence. How can Fallon get word back to his fellow Treasury cops?

White Heat took screen violence to a new level. It had a big impact when new, and audiences still rally behind its out-of-control mayhem. The tightly constructed production became a model for the studio’s heightened cutting style. Raoul Walsh doesn’t hold shots for emotional effect. Day turns to night during a chase scene in four fast cuts. The explosive ending rushes past a ‘The End’ card so quickly, we don’t know what’s hit us.

James Cagney had avoided gangster roles for a decade, but when deciding to re-join Warners realized that a gangster update was the surest way to revive his career. White Heat has no use for moody romance or melancholy, and instead suggests that crime and societal chaos are rushing toward some kind of apocalypse. Evidence that the country is fresh from a war are everywhere. The improved communications and coordinated planning of modern warfare have been applied to the pursuit of criminals. As if proposing that the country’s war machinery needs to be turned loose on domestic problems, an entire army converges on Cody Jarrett. He’s not caught in a ‘lonely warehouse’ but in a gigantic oil refinery. The setting is a technological labyrinth, as strange as the circuit board of a computer.

Cody knows how to game the system to outfox the law, but he never understands that new technology is tripping him up, along with the classic gangster pitfall, personal betrayal. Despite being a vicious renegade Cody maintains strong personal ties (“What’s mine is mine”). His mother is a Ma Barker-type psychopath in her own right. He suffers from scorching migraines that only Ma can calm, violent seizures that echo the ‘white heat’ of the title. Cody sits on his mother’s lap. Call it Oedipal or whatever, the relationship is outrageous.

White Heat replays classic gangster riffs with a new level of violence and sadism. Victims not casually executed with pistols are threatened with gruesome industrial ‘accidents.’ The luckless henchman ‘Zuckie’ is scalded by a literal white heat, a blast of steam. Elsewhere we witness brutal beatings and a cold-blooded murder in the trunk of an automobile that still chills: “Okay Parker, I’ll give ya a little air!” An extended prison section outdoes all the earlier Big House epics; the finish is an elaborate caper that looks forward to the multi-climaxed action cinema of today.

Next stop 007, courtesy of the light-fingered Ian Fleming.

White Heat was a major influence on thriller culture, at multiple levels. Cody Jarrett takes on a Fantomas-like aura: his own confederates fear him and behave as if he has supernatural powers. When he’s caught dead to rights with a shotgun, Jarrett’s maniacal laugh makes Hank Fallon unsure if he indeed has the upper hand. Ian Fleming must have been a huge fan of the movie, for he appropriated much of it for his 007 super-spy franchise, including the idea of a man waiting beside a decoy bed to ambush an assassin (Big Ed and Cody / James Bond and Professor Dent in Dr. No). The last act of White Heat provided a template for Fleming’s Goldfinger. Undercover operative Fallon must accompany Cody on his biggest heist, a caper verbally compared to a raid on Fort Knox!

The film version of Goldfinger copies even more details. At the eleventh hour, both robberies are thwarted when the heroes make desperate attempts to reach the authorities through elaborate radio homing devices. Both Fallon and Bond leave notes behind them, hoping that the messages will get to the right people. In both cases the big caper is interrupted by a military assault. White Heat gives Fallon a legitimate reason to tag along with Cody’s gang … James Bond’s screenwriters must confect an unlikely reason for Auric Goldfinger to keep 007 alive.

White Heat is forward-looking in other ways too. With the war five years gone hundreds of thousands of experienced ex-soldiers swell the ranks of law enforcement. With its new anxieties and neuroses, the unstable world is rushing toward a nervous breakdown right along with Cody Jarrett. There’s something grandiosely appropriate about Cody’s self-willed immolation atop a million gallons of gasoline. The cascade of conflagrations bring the gangster film up to date with the atomic age.

Along the way we have plenty of terrific performances to enjoy. Steve Cochran is swarthy and uncouth, Virginia Mayo is delightfully cheap (snoring, spitting out chewing gum) and Margaret Wycherly’s daffy old nut is so convincing she’s not even funny. It’s also fun seeing actor Mickey Knox in an early role as one of Cody’s gang. In his Italian exile, Knox became more famous as the translator and English version producer for a pair of Sergio Leone classics.

Although it’s much newer than the other pictures White Heat was much improved over it’s older DVD. We immediately see how much Eastman’s film stock had improved since 1936. The HD transfer is as sharp as a tack. We can now clearly identify which Jarrett Gang members are getting blasted down in the final battle in the refinery, even in long shots.

The novelty extras are the Joe Doakes comedy short So You Think You’re Not Guilty, the Bugs Bunny cartoon Homeless Hare (not HD), a newsreel and a trailer for The Fountainhead. The featurette docu Top of the World is one of the better in the set, with a contribution from critic Andrew Sarris among the gathered experts. The feature commentary is by Dr. Drew Casper.

Warner Bros’s Blu-ray set Ultimate Gangsters Collection: Classics is a winner. Each of these titles could have found its audience on its own. The package include a fifth DVD disc containing Warners’ long-form docu Public Enemies: The Golden Age of the Gangster Film. It has plenty of clips, which access a few glimpses of the one iconographic ’30s gangster saga not produced by Warners, Howard Hughes’ Scarface. The docu is a bit on the superficial side but a good intro just the same. The disc also contains six Looney Tunes and Merrie Melodies cartoons, each with a gangster theme or two. One of the cartoons has a full-on lampoon of Bette Davis and Leslie Howard in The Petrified Forest.

Not repeated from the 2013 release is a 32-page mini-book, that recapped some info and quotes from the four pix in question, accompanied by some illustrations. It’s not missed.

We don’t talk too much about prices at CineSavant but are quick to explain when discs become more economical. Twelve years later, after all the inflation we’ve seen, this collection costs $20 less than did the first release.

Reviewed by Glenn Erickson

Ultimate Gangsters Collection: Classics

Blu-ray rates:

Movies:

Video: Excellent

Sound: Excellent

Supplements: detailed above after each title.

Deaf and Hearing-impaired Friendly? YES; Subtitles: English (feature only)

Packaging: Four Blu-rays and one DVD in Keep case

Reviewed: July 27, 2025

(7363gang)

Visit CineSavant’s Main Column Page

Glenn Erickson answers most reader mail: cinesavant@gmail.com

Text © Copyright 2025 Glenn Erickson