The harsh reality is that this order will criminalize already-vulnerable people who are in need of care, putting our communities in danger.

by Regan Huston,

August 5, 2025

Last month, President Trump signed an executive order aimed at forcibly locking unhoused people experiencing mental health crises or substance use disorder in involuntary commitment in state psychiatric hospitals.1 Here’s the issue with that measure: it is nothing more than an attempt to disguise criminalization as care.

As the number of people experiencing homelessness in the U.S. soars and social supports are stripped away, this move will undoubtedly expand the criminal legal system.

The truth about involuntary commitment

The order directs the federal government to find ways to encourage and empower states to force unhoused people experiencing mental health or substance use issues into involuntary commitment facilities.

These state psychiatric hospitals aren’t typically run by departments of correction, but they are in reality much like prisons. At least 38 states also allow involuntary commitment for substance use disorder treatment, and evidence suggests that these supposed “treatment facilities” are not effective. Notably, it can be extremely difficult for these “forensic patients” to be released as they may remain hospitalized for decades or for life.

Involuntary commitment is not only legally and ethically dubious, but it also fails to deliver on the very objectives that justified its creation.

Contradicting cuts

Notably, in the first five months of his second term, Trump has gutted social programs that have been proven to reduce crime and keep people off the street.

First, the administration slashed $11 billion from addiction and mental health programs, a move that will lead to increasing prison and jail populations. Then, it targeted Housing First programs, a method that has been proven effective at getting and keeping people off the street, by giving them access to housing without conditions. And, last month, Trump’s “big, beautiful bill” came with an ugly reality: Steep cuts to Medicaid that will leave 10 million people uninsured, making it nearly impossible for them to access mental health care or substance abuse treatment.

At the same time, it has tried to end harm-reduction strategies that aim to reduce overdoses and the negative health effects of drug use. The administration’s actions are contrary to public health research that shows that harm-reduction work.

With the safety net shredded, what will happen to the people who desperately need care? In many cases, they’ll be put straight into actual prisons and jails, which are never appropriate places for treatment.

Shuffled into the system

The administration has made it clear that it would rather shift money away from care and turn toward expanded criminalization.

Prisons and jails are often viewed as de facto mental health and substance abuse treatment providers, but the reality couldn’t be further from the truth. Rates of mental illness are exceptionally high among incarcerated people, and these facilities fail to meet the demand for help. More than half of the people in state prison reported having a mental health problem, yet only 26% received professional help since entering prison.

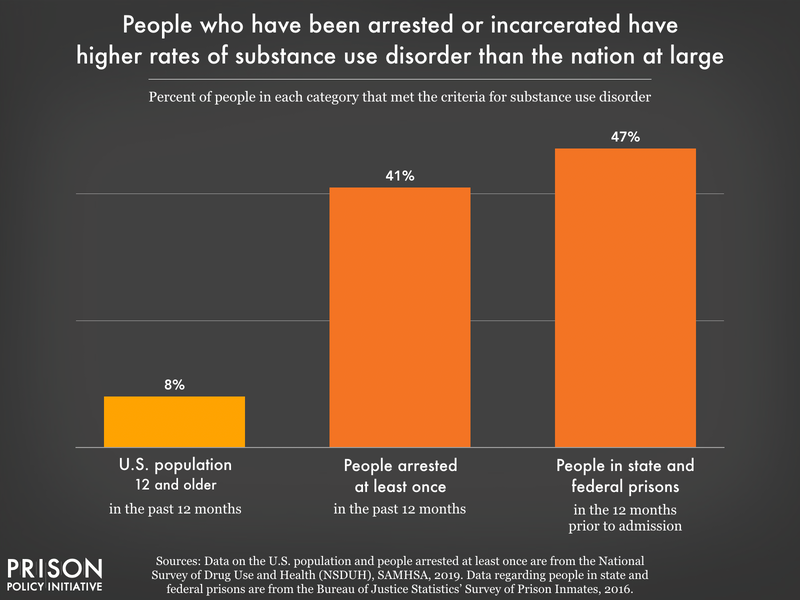

Based on 2019 data from the National Survey of Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) from SAMHSA, approximately 8% of people over the age of 12 met the criteria for a substance use disorder, and 41% of people who had been arrested in the last year met the criteria for a substance use disorder. In 2016 (the most recent year for which the Bureau of Justice Statistics published national prison data), 47% of people in state and federal prisons met the criteria for a substance use disorder in the 12 months prior to their most recent prison admission.

Not only are prisons and jails unable to treat mental health problems, but they can also create them. Incarceration itself is traumatizing and can inflict serious mental damage on people. Violence behind bars is inescapable and can result in post-traumatic stress symptoms, like anxiety, depression, avoidance, hypersensitivity, hypervigilance, suicidality, flashbacks, and difficulty with emotional regulation.

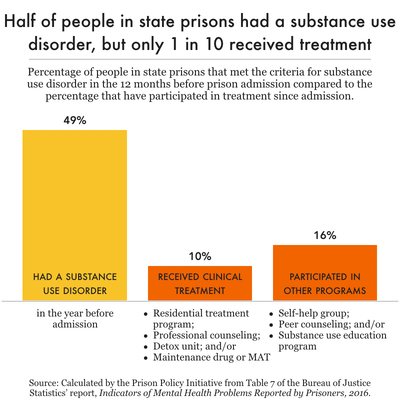

Prisons and jails are not treatment centers for substance use disorders, either. In fact, these facilities punish drug use far more than they treat it. People who have been arrested or incarcerated have higher rates of substance use disorder than the general population. And, disturbingly, only 1 in 10 people in state prisons with substance use disorders received treatment.

Jails, which tend to have even fewer resources, are also not suited to offer care. The most effective treatment options are the least accessible for people with opioid use disorder: Just 19% of jails initiate medication-assisted treatment for people with opioid use disorder.

Behind bars, people don’t have access to the care they need – and upon release, they’re often left worse off than before incarceration. Formerly incarcerated people are almost 10 times more likely to be homeless than the general public. And, being homeless makes formerly incarcerated people more likely to be arrested and incarcerated again, creating a revolving door.

Attacks on people experiencing homelessness

The reality is that there is an inextricable link between housing, mental illness, drug use, and criminalization. Yes, people experiencing these vulnerable situations often need care — but forcibly hospitalizing them is not the solution.

Instead, the U.S. must embrace Housing First. This method offers housing with no strings attached. It recognizes housing as the first step in responding to homelessness, rather than something to work toward. It also does more than simply put a roof over people’s heads; it gives people the space and stability necessary to receive care, escape crises, and improve their quality of life. Research shows that this approach keeps people housed and improves attitudes and outlook on life.

Conclusion

In the last year, there have been rampant attacks on people experiencing homelessness – and this executive order is the latest example. It’s a bad move that will result in far more people locked up simply because they’re experiencing homelessness, mental health crises, or substance use issues. Gutting proven solutions that make communities safer — like community-based care, Housing First, and harm-reduction efforts — seems to be a pattern with the administration.

The good news is that state and local governments don’t have to help this misguided effort. The federal government will certainly dangle funding to entice them to implement these policies, but they have the ability to say no. If the money comes with these types of strings attached, it isn’t worth the cost.