UCSD students board a Blue Line trolley at the UC San Diego station. (Photo by Chris Jennewein/Times of San Diego)

UCSD students board a Blue Line trolley at the UC San Diego station. (Photo by Chris Jennewein/Times of San Diego)

San Diego’s largest public-transit investment, the trolley’s Blue Line extension up to University City, was set to open in 2021 – a year after the state’s biggest transit project, high-speed rail, was supposed to start zipping riders from Los Angeles to San Francisco in under three hours.

But the two projects ended up taking very different paths. Billions of dollars later, only San Diego’s extended trolley has opened its doors, while years of delays and ballooning costs continue to plague the California High-Speed Rail project – with no completion date in sight.

Now, experts believe San Diego’s ambitious Blue Line extension may hold the key to solving the state’s high-speed rail crisis, according to a new report by local transportation nonprofit Circulate San Diego.

While both projects garnered billions in funding, voter backing and environmental approval, the report, which was released Monday, states that these factors alone aren’t enough to push public transit projects to completion under California’s construction policies.

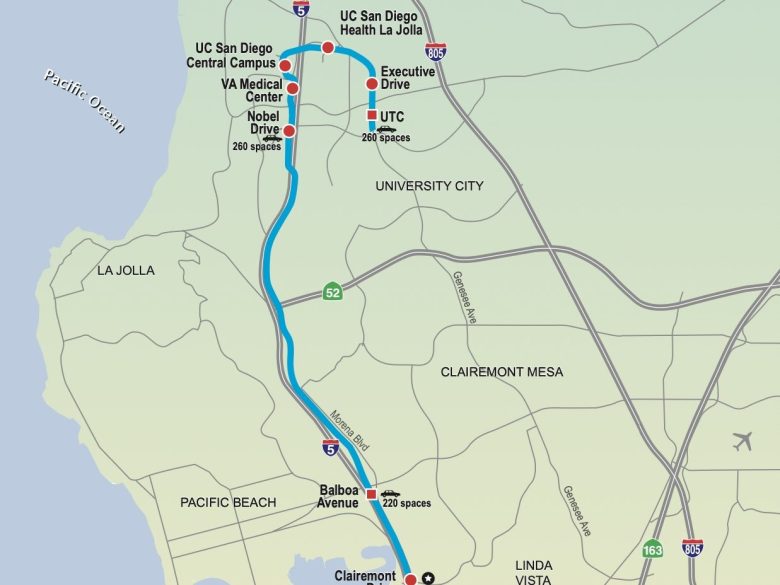

Through San Diego’s ambitious Blue Line trolley extension, riders are now able to take the trolley from University City all the way down to the U.S.-Mexico border. (Photo courtesy of San Diego Association of Governments)

Through San Diego’s ambitious Blue Line trolley extension, riders are now able to take the trolley from University City all the way down to the U.S.-Mexico border. (Photo courtesy of San Diego Association of Governments)

Instead, the report points to “arbitrary, excessive and avoidable” bureaucratic red tape as the key factor determining whether public transit projects will succeed — or stall.

These bureaucratic hurdles come in the form of permits, which public transit builders must obtain from communities their projects affect — including city governments and state agencies — before they can start construction.

Because permitting power rests in these officials’ hands, the report says that they can delay projects for years, demand unrelated changes and hike up costs — all as builders are “powerless” to intervene.

“We need to take a hard look at our policies in blue states to make sure that we are not standing in our own way to get the good public goods and services that we need,” said Colin Parent, the report’s author and Circulate’s chief executive officer.

“We can’t have an abundance of public transit with the systems that we have today.”

The power of coordination

One of the few powers builders have in the face of these obstacles is coordination with other public-transit agencies in the region.

While this is difficult in places where public-transit authority is fractured into many different agencies and jurisdictions, San Diego stands out to experts.

A North County Transit District bus. (Photo courtesy of NCTD)

A North County Transit District bus. (Photo courtesy of NCTD)

The Los Angeles and Bay Area regions each have 27 different transit agencies, while San Diego has a streamlined public-transit system operated by just two: the San Diego Metropolitan Transit System and North County Transit District.

Furthermore, San Diego’s public-transit planner, the San Diego Association of Governments, has to coordinate its projects with only one county. To contrast, the Bay Area’s public-transit planner must navigate nine.

This streamlined system makes a difference. Circulate’s report highlighted easy coordination as a key factor behind the success of San Diego’s Blue Line extension.

The report stated that it enabled public-transit authorities to gain approval from areas where the extension would pass through — including the city and University of California San Diego — in an “early and consistent” manner.

San Diego trolley among ‘rays of hope’ for high-speed rail

While the Blue Line extension is a case study in coordination, California’s high-speed rail project is the poster child for how the permitting process can derail public transit. But experts believe high-speed rail can take lessons away from San Diego.

The rail project is decades off schedule and about $100 billion over budget — even though no segments have been completed. Permits are a key culprit, the high-speed rail system’s oversight agency found.

Bridge construction for the bullet train in the Central Valley. (Photo courtesy of California High-Speed Rail Authority)

Bridge construction for the bullet train in the Central Valley. (Photo courtesy of California High-Speed Rail Authority)

Officials from numerous local jurisdictions where the rail system will pass through, including Wasco and Madera County, have saddled the project with delays and millions in unforeseen costs throughout the permitting process.

For example, in a 2018 settlement over the project, the city of Shafter required the California High-Speed Rail Authority to build “very expensive infrastructure for the city, earlier than when we would’ve been able to accomplish it by ourselves,” City Manager Scott Hurlbert said.

There’s a clear difference in scale between San Diego’s trolley extension and the sprawling, statewide rail project — a key factor that weighs heavily on the permitting process. The larger and more ambitious a public-transit project is, the more permits and coordination it requires — opening up more room for delays, cost hikes and uncertainty.

“For high-speed rail, we’ve seen time and again that local government and special districts hold the project hostage to extract extra money or extra infrastructure,” Parent said.

But San Diego’s centralized public-transit system helps builders through the permitting process by simplifying coordination and giving SANDAG special powers to override local permit refusals.

“That shows that granting these transit authorities more responsibility can lead to better outcomes,” Parent said.

Lessons from San Diego

While these powers haven’t always shielded SANDAG from the high costs and delays that can stem from the permitting process, Circulate’s report highlighted the Blue Line extension as a standout success that arose from this system.

In many jurisdictions outside of San Diego, transit authority is more decentralized — a result of laws championed by community advocates in the 1970s who sought to give the public a greater voice in public infrastructure projects.

These reforms followed decades of unchecked development, when these projects destroyed communities and displaced primarily disadvantaged residents.

San Diego Trolley downtown. (Photo by Chris Stone/Times of San Diego)

San Diego Trolley downtown. (Photo by Chris Stone/Times of San Diego)

Circulate isn’t calling for a return to those days. But Parent cautioned that today’s permitting requirements have created a new set of burdens — even as California pours billions of dollars into public transit to meet its climate goals.

Instead, Circulate’s report calls for a more balanced system: allowing transit builders to grant themselves permits if communities don’t make decisions within a set deadline.

A similar approach may make its way into state law. This year, Democratic state Sen. Scott Wiener introduced a bill that sets deadlines for community officials to communicate with public-transit builders throughout the permit process, specifically to quicken the high-speed rail project.