It’s an early Monday morning and I’m standing in the first-floor reading room of The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza, where the windows open onto Elm Street.

Outside the pane glass, vendors offer overpriced, half-baked tours to the out-of-towners and the suburban tourists who take turns running out to stand on the “X” that marks the spot where President John Fitzgerald Kennedy was slain on Nov. 22, 1963. Business as usual in Dealey Plaza. Business as always.

Inside this quiet brick-and-glass space, the museum’s curator, Stephen Fagin, has laid out more than a dozen black-and-white photographs, all taken by Dallas Times Herald photographer Bob Jackson, whose fame long outlived the shuttered newspaper.

Some of the photos are of Dallas in the 1960s and ’70s: cops at a fatal crash along a desolate stretch of Cockrell Hill Road, circus elephants trundling through downtown, Theater Row when it was more than just the Majestic. Famous faces, too, stare out from a few pictures: Byron Nelson with Bob Hope, cookbook author Helen Corbett serving her boss Stanley Marcus, the Beatles at Memorial Auditorium, Dallas Cowboys coach Tom Landry posing at old Ownby Stadium, John Wayne at Neiman Marcus for a Fortnight.

News Roundups

Amidst the glossies, Fagin had placed a small box delivered by the 91-year-old Jackson in recent months as he turned over his entire archives to the museum — some 15,000 images, negatives and prints, spanning his tenure at the Times Herald.

One of those moments when Bob Jackson proved he wasn’t just good but also lucky: a photo of three girls poking their heads out of a City Park Elementary window on Sept. 6, 1961

Courtesy Bob Jackson/Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza

Jackson’s donation, being reported here for the first time, is among the most significant ever made to the museum and a turning point in its 36-year history as it looks to become much more than just The Place Where Kennedy Was Killed. This space in the old Texas School Book Depository aspires to become what this city sorely lacks: a museum that tells this city’s unexpurgated, unabridged story.

Jackson’s expansive archives document the profound and detail the mundane during the years before and after Dallas wrestled with the stain of being one of the world’s most infamous crime scenes.

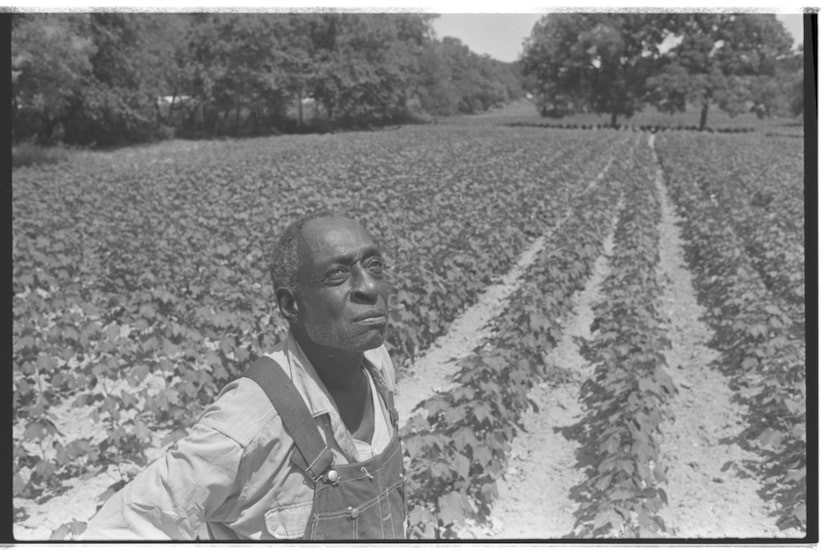

There’s a photo of two Black children taken at Elisha M. Pease Elementary School when that school was finally desegregated in September 1963, two years after Dallas became the last large Texas city to begin desegregating (some of) its schools. There’s another of a Black man in overalls standing among his crops along Hillcrest Road in 1967, of which Jackson is particularly proud.

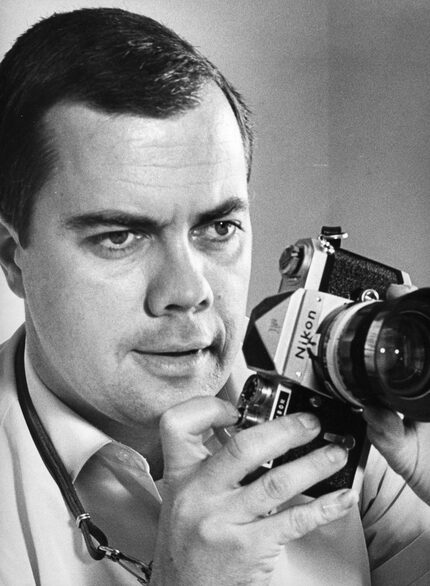

Bob Jackson on the job for the ‘Dallas Times Herald’ in the 1960s

Courtesy Bob Jackson/Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza

Jackson’s vast collection, filled with the famous and the forgotten, is but the latest and largest building block toward the museum’s goal of becoming Dallas’ Museum, even in the midst of its ongoing negotiations with the county over the building.

“We were the suitable repository for looking after his collection, which is far beyond just covering the assassination weekend,” Nicola Longford, the museum’s CEO, said as we pored over the photos and negatives now being scanned and stored. “We are really honored that he decided that we were the appropriate home — including his camera, which will be part of this gift.”

That gift includes the negative of one of the most famous and unforgettable images of the 20th century. Which brings us back to the box.

Fagin opened the small container, noting that it holds Jackson’s original negatives from November 1963. One dates from Nov. 24, 1963. In that photograph, a nightclub owner fires his .38-caliber Colt Cobra into the gut of an accused presidential assassin handcuffed to a besuited Dallas homicide detective wearing a Stetson.

That photograph consumed most of the front page of the Nov. 25, 1963, edition of the Dallas Times Herald, above a brief explanation of how Jackson had captured “the historic photo … at the precise moment the bullet from Jack Ruby’s pistol entered the body of Lee Harvey Oswald.”

“Photographer Jackson,” said the note, “has recorded for history one of the most bizarre and dramatic moments.”

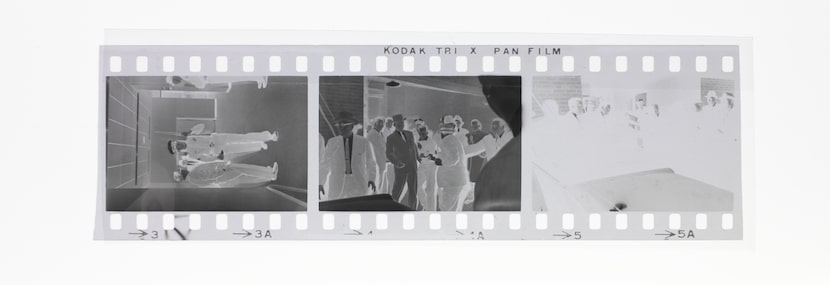

Before he captured the Pulitzer Prize-winning photo of Jack Ruby shooting Lee Harvey Oswald, Bob Jackson took a photo of a Dallas police officer carrying a rifle he’d found in an East Texas lawman’s car parked in the Dallas PD basement. At right is the next photo he took, of police tackling Ruby, but his strobe hadn’t yet reset.

Courtesy Bob Jackson/Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza

Fagin, hands gloved, asked if I want to see “the negative,” emphasis on the. Of course, I told him.

“It’s … it’s … history,” Fagin said as he removed it from the box, then from its sleeve. “It’s extraordinary. A picture you have seen a million times.”

I turned to Longford, standing near the table’s edge, and asked when she first saw the original negative.

“I actually have not seen this,” she said. She seemed to back away from the table, maybe a step or two. I asked how it felt to have the original now in the museum’s possession.

She took a long pause.

“I don’t really have words,” Longford said. She took a deep breath. “I would like time alone with it.”

“I didn’t want to auction everything off”

Bob Jackson, calling from his home near Colorado Springs, Colo., is quick to answer when asked why he donated his archives to the Sixth Floor Museum.

“Because that’s where I think they ought to be,” he said. And because he didn’t want his six children and 12 grandchildren to have to deal with it — or going through it, piece by piece, taking what they wanted and abandoning the scraps to the dustbin of history.

A man leaps across a puddle of water during a Dallas downpour on September 27, 1966.

Courtesy Bob Jackson/Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza

Jackson and the Times Herald have always had close ties to the Sixth Floor Museum. In 1989, the paper, which was bought and closed by The News two years later, provided the museum’s original project director, Conover Hunt, with some 1,500 negatives that became “the foundation of our collections here,” Fagin said. In 2014, former Times Herald photographer Eamon Kennedy donated another 1,200 photographs, most from Kennedy’s arrival at Dallas Love Field and Jack Ruby’s trial.

Jackson provided an oral history in 1993, assisted with countless education programs over the years and was featured in an exhibition, “A Photographer’s Story,” that ran from February 2009 through October 2010. Longford frequently refers to him as a “longtime friend of the museum.”

Jackson could have easily sold his archives to the highest bidder. “But I didn’t want to auction everything off and have it go to a collector and have nobody see it again,” he said.

He held on to everything, too, including every negative of every image he captured while on the Times Herald’s payroll from 1960 until, give or take, 1974. (He spent a year at The Denver Post in the late 1960s.) Longford said the donation was a long time in the making but came together only in the last year.

Longford said Jackson’s is the largest donation of images the museum has ever received, surpassing The Dallas Morning News’ collection handed over in 2014.

The Beatles and, at top right, manager Brian Epstein spoke to Dallas media before their concert at Memorial Auditorium on Sept. 18, 1964.

Courtesy Bob Jackson/Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza

For years, Jackson stored the negatives in a safe deposit box, until he grew weary of traveling to the bank every time he needed to make a print. Before the photos returned to Dallas, they were stashed away in his Colorado basement.

Jackson is a born-and-bred local, a son of Highland Park and graduate of its high school, where he took pictures for the school newspaper and the yearbook. That was the extent of his formal training before he landed at the Times Herald in 1960, when former Dallas Morning News managing editor Felix McKnight added Jackson to a burgeoning staff of shooters.

His early stuff consisted of cute kids on big bikes and elephants marching from the railyards to Memorial Auditorium — front-page filler. But even early on, Jackson captured some of the most significant, unforgettable images ever taken by a Dallas photojournalist, among them a picture of three little girls — one Black, one Hispanic, one white — poking their heads out of a City Park Elementary window on Sept. 6, 1961, when 8 Black children stepped foot in a handful of white Dallas elementary schools for the first time.

“I was there to get the kids on the first day of integration, and when the three girls looked out, I thought, ‘Here’s the picture,’” Jackson said. “I was certainly excited to get that. That was pure luck, being in the right place. Eddie Hughes, who worked for the Dallas News, was standing next to me. He was a reporter and he quite often carried a camera, but he didn’t have a telephoto lens. I did.”

Jackson was good. And he was lucky. And two years later, he became one of the most famous photographers in the world.

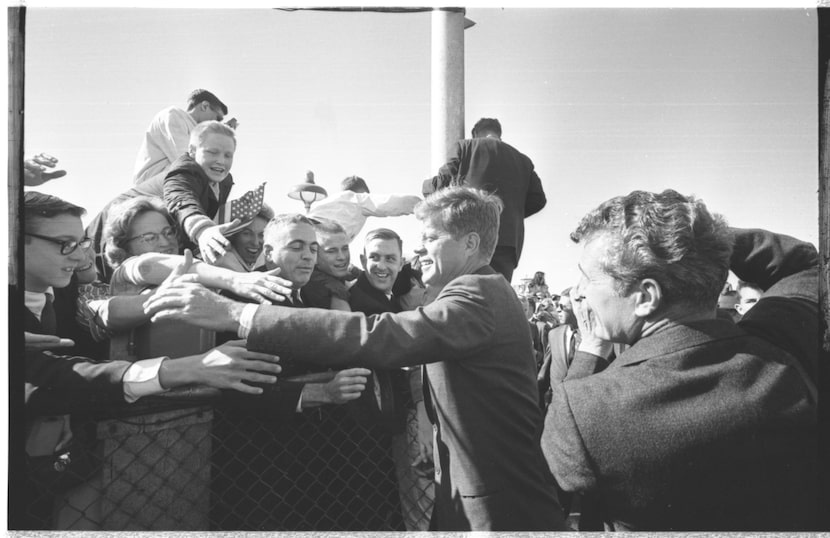

This is one of Bob Jackson’s favorite photos of President John Kennedy’s arrival at Dallas Love Field. He stayed beside the president as he worked the fence line, shaking the hands of well-wishers who’d come to the airport to welcome him to Dallas.

Courtesy Bob Jackson/Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza

Ruby, Oswald and six-tenths of a second

Jackson’s donation includes dozens of photos taken on Nov. 22, 1963, most from Dallas Love Field, where he was among the numerous photographers assigned to capture John and Jackie Kennedy’s arrival. His favorite photo from that morning is of the president reaching across the fence to shake hands with the throng of well-wishers who’d descended on the airport.

The photographer left Love Field in the back of the motorcade, with the intention of handing off his film rolls to reporter Jim Featherstone at the intersection of Main and Houston streets as they trekked to the Dallas Trade Mart for the president’s scheduled speech. Along the way, Jackson took a few photos of the crowds along the motorcade tour, but not as many as he now wishes he had: “It was repetitious,” he said with a small laugh.

He famously emptied his camera just before turning the corner for the Texas School Book Depository, which meant he couldn’t capture what he’d seen after hearing three shots ring out in Dealey Plaza — a rifle peeking out the sixth-floor window. Bad timing. Bad luck.

Two days later, Jackson was in the basement at Dallas Police Department headquarters awaiting Oswald’s transfer when he took a photo of a patrolman carrying a rifle – which, as it turned out, belonged to a visiting East Texas lawman who’d left it in his car parked in the basement. The next photo on that roll was the shot of The Shot, taken six-tenths of a second after The News’ Jack Beers Jr. snapped his photo of Ruby aiming his pistol at the accused assassin, still staring straight ahead, his lips pursed. Jackson immediately took another photo, of a mass of men swarming Ruby, but his strobe hadn’t reset.

Bob Jackson was toward the end of the motorcade at it headed toward the Triple Underpass on Nov. 22, 1963. He took some photos of the crowds wanting to see President John Kennedy. But he wishes he’d taken more.

Courtesy Bob Jackson/Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza

Beers’ photo for the morning paper hit the wires first. Jackson’s editors asked if he had a better picture than The News’. He wasn’t sure. The Herald’s Vivian Castleberry would later recall that when the staff saw Jackson’s developed photo, “All of Dallas could have heard the screaming from that room.”

McKnight and Times Herald publisher Jim Chambers did the unthinkable, giving Jackson full ownership of the negative. In 1995, McKnight told the Sixth Floor Museum. “I’ve always been very proud of that decision … because it lifted a heck of a lot of spirits around there.”

Jackson told me snapping that photo “made up for not being able to get anything” from Dealey Plaza on Nov. 22. “I felt a little better about that.”

Jackson would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize. Beers died in 1975, at 51 years old, of a heart attack. His family would later tell this newspaper that he was felled by depression, caused, at least in part, by a photo taken a fraction of a second too soon.

One of the photos of which Bob Jackson is most proud is this image of an unnamed farmer on his Hillcrest Road land, taken in August 1967

Courtesy Bob Jackson/Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza

The Sixth Floor Museum will host Jackson for a formal handover on — when else? — November 22, during a discussion called “Dallas: Through the Lens of Bob Jackson.” He’s been promised only a little of the presentation will focus on The Shot. He would prefer instead to focus on the overlooked, the misremembered, the images overshadowed by myth.

We spoke for two hours a few days ago. And before we hung up, I asked him how he felt about his photographs being the cornerstone of Longford’s intentions of turning the Sixth Floor into a museum for and about all of Dallas. He thought for a moment, then spoke of all the colleagues and friends who died long ago, of a childhood home in Highland Park torn down for “the ugliest house you’ve ever seen,” of moments not captured.

“I’ve thought back over the years about the time when I could have taken pictures of Dallas for something like that, a history of Dallas, and I didn’t do it,” Jackson said. “I missed a lot of things. But,” he said, chuckling, “at least I can contribute some stuff.”