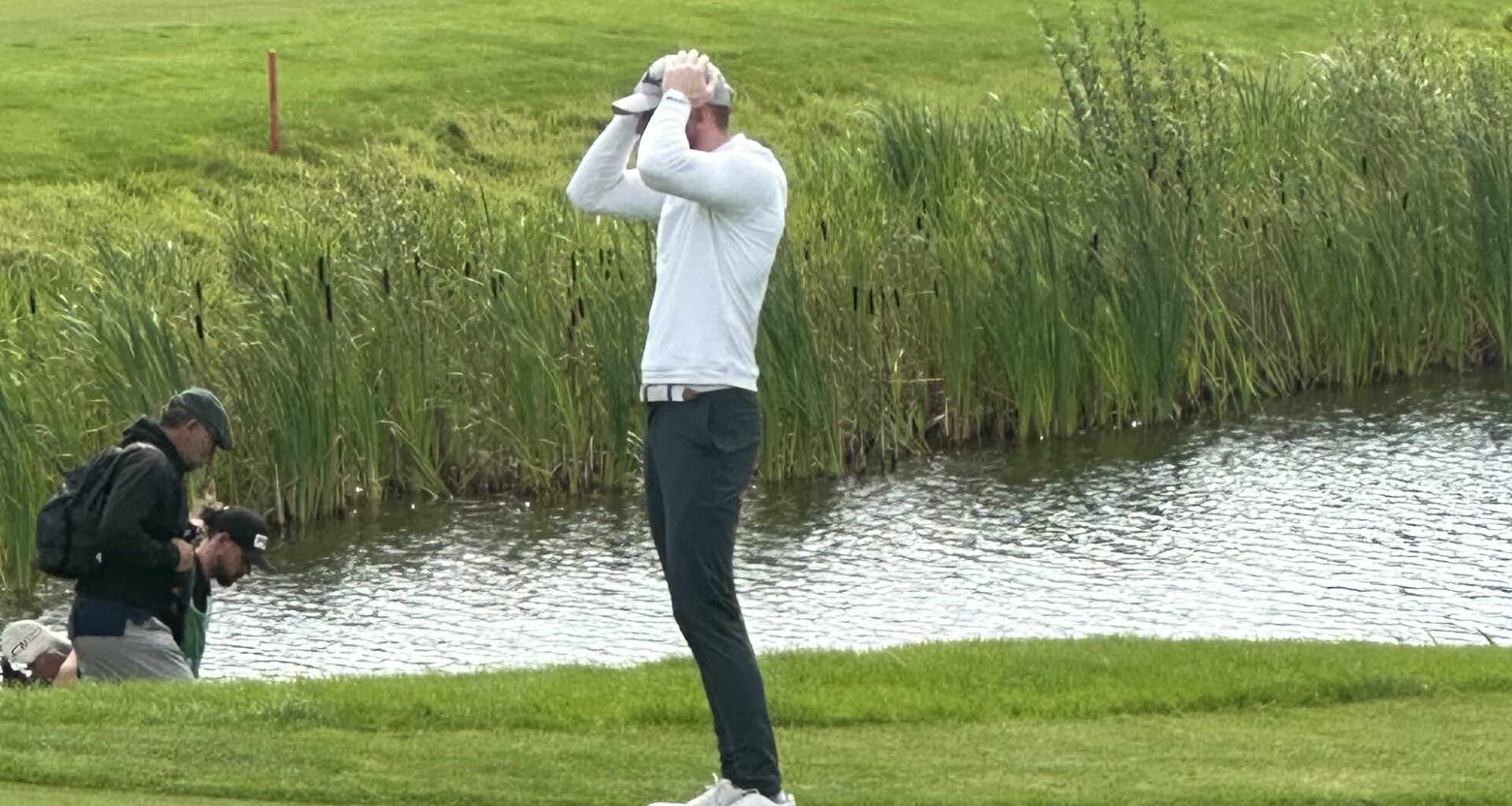

COUNTY MEATH, Ireland — John Murphy stood on the green with his hands on his head. He and his caddie had misread the wind, and the 5-iron he thought he had hit perfectly splashed in the pond guarding the green. Standing behind the green, his girlfriend’s sister uttered, “Oh, no. Oh, God, no.” Family members frantically looked up and down the bank, hoping for a miracle. But the ball was gone, and his chances of making his first cut in a year had drowned with it.

Murphy removed his gray Titleist hat and ran his hands over his face and through his bright red hair. It was as if he was trying to wake up from a nightmare he had experienced again and again over the last two years.

I met Murphy for the first time at the 2022 Pebble Beach Pro-Am. The bright red hair and thick accent left no doubt of his Irish heritage. He had turned pro the previous year after a decorated college career at Louisville and soon after was playing in the final group at the Dunhill Links on the European Tour, where he would finish ninth. Although he missed the cut in California, the 27-year-old Irishman appeared headed for stardom.

In professional golf, however, things don’t always go as planned.

In 2023, Murphy earned European Tour status through Q school, and as the season began, so did his struggles with the driver. He made just three of 23 cuts and lost his card. In 2024, he fell back to the HotelPlanner Tour (nee Challenge Tour), but the struggles continued. Murphy made just two of 19 cuts, and in the blink of an eye, he had lost all of his status.

I caught up with Murphy on Wednesday at the Irish Challenge on the HP Tour. He needed a last-minute sponsor’s invitation just to get into the field. His last made cut had come a year ago, at this very event. As always, Murphy was friendly, upbeat and candid. He opened up about his struggles, but said for the first time in a long time, he felt encouraged about his game. “I’m not sure if it was technical or mental,” he said. “Those lines get blurred when you’re struggling.” But he was buoyed by a recent coaching change and believed he was heading in the right direction, albeit slowly.

Although there have been more missed cuts this year, there were encouraging signs, including a 65 a few weeks earlier that left him just one off the cut line.

Murphy opened with a solid 2-under 70. My plan was to catch him at the turn on Friday and write a story about him making his first cut of the year. Sure enough, he played his first six holes on Friday in 2 under par and moved into third place early on the second day. Everything was going according to plan.

He then bogeyed two of the last three holes on his front nine before he walked to the 1st tee (his 10th). Hitting last, he held a wedge in one hand and his driver in the other. He has stopped using a conventional tee; instead, he builds a turf one with a wedge, à la Dame Laura Davies.

The tee shot went directly to the right, and Murphy instantly dropped his club. It was a reminder that although he had improved with the driver, the struggles weren’t gone. He salvaged par with a 15-footer, and although a par-saving putt like that might have served as an opportunity to build momentum, this one offered only a short sense of relief.

As I stood behind the tee of the next hole, Murphy approached, and as always, he was friendly and upbeat.

“Going to have a few pints?” he asked me as he headed to the tee of the par-5. “Still recovering from a couple of nights ago,” I replied as he walked past and laughed.

The 2-iron Murphy hit off the 2nd tee, a dangerous hole with water left and fairway bunkers right, was proof that the immense talent is still there. With its low penetrating trajectory, the ball took off like a rocket, a tight draw that finished perfectly, 260 yards or so down the fairway.

But then he hit driver off the deck, a smothered shot that dove quickly left into a deep fairway bunker 70 yards short of the green. It led to a bogey, and suddenly he was creeping back toward the cut line.

On the 3rd hole, I approached Murphy’s mom, Carmel, who was standing alone in the knee-high heather to the right of the fairway. Situated far ahead of the others following John, she wore sunglasses and a white cap from the Byron Nelson, a PGA Tour event John played in 2022. Her coat was filled with sponsor patches from the start of his pro career.

I introduced myself, mentioned I was writing about her son, and asked if I could ask some questions.

“John should get a medal for resilience and perseverance,” she said while telling me about the hard work he puts in daily despite the years-long slump.

When I asked if it was hard to watch her son struggle like this, she said, “As long as he believes, I believe.”

As Murphy approached his perfect drive on the 3rd, his father, Owen, was far behind, slowly making his way up the fairway. He struggles badly with his feet, and even from a distance, you could detect his significant limp. “He shouldn’t be out here,” Carmel said. “I told him to rest.” But with John hovering around the cut line, Owen wasn’t going to miss a shot.

Carmel rarely took her eyes off her son, and as we watched his approach shot finish 25 feet behind the hole, she said, “A par here will steady the ship.” She said goodbye and quickly headed for the green, staying ahead of the small gallery that was following the group.

A bogey on the following hole, a missed short birdie putt on 14, followed by a par on the tricky par-3 6th (his 15th), left Murphy at 1 under for the tournament and directly on the cut line at the time.

The 7th at Killeen Castle, a Jack Nicklaus design, is a reachable par-5, assuming you can navigate the demanding drive. It requires taking the tee shot over a large group of trees down the right side while avoiding the deep fairway bunkers guarding the left.

It was the type of drive Murphy had struggled with over the last few years, and now the cutline was looming. I stood in the right trees near his mother, girlfriend, and his girlfriend’s sister. Understandably, no one was talking.

After Murphy’s drive landed perfectly, Carmel took a deep breath and headed for the green.

The green is guarded by water short and left, and Murphy would have to carry the entire length of hazard. The wind had kicked up, and from where I was standing, it felt like it was helping.

Near the green, the Murphy clan was scattered in the heather.

After the round, Murphy told me he made one of his best swings of the day with the 5-iron, but that the wind had switched as he hit or he and his caddie had misjudged the wind direction. The ball splashed in the water close to the bank.

The other two players in the group then hit their approach shots, and although both avoided the water, they both came up significantly short, an indication the wind had deceived all three players.

Murphy stayed back near the edge of the pond, just ahead of where he had taken his second shot, while his family rushed to the bank. The search began in hopes of somehow finding the submerged Titleist.

After a few minutes, Jiri Zurska, Murphy’s friend and former Louisville teammate, one of two other players in the group, formed an X with his arms. It was a sign to Murphy that the ball could not be found.

After a drop, Murphy barely made the green with his fourth shot, leaving a 70-foot putt to save par. He stood with his hands on his head, the first time all day his body language indicated anything other than confidence. He crouched and rubbed his face with both hands. It was a scene that has played out far too often. The bogey dropped him below the cut line for the first time all week, a mere eight holes after his name was in third place on the leaderboard.

On the par-3 8th, he found the right bunker, and his shot didn’t check up and ran into the fringe. Another bogey. Carmel leaned against a tree behind the green as her son lined up his par-saving putt. When it slid by, she sighed, lowered her head, turned, and headed for the next hole.

The wind picked up as Murphy approached his 18th hole, a relatively benign par-4. There was hope the cut would move later that afternoon (it did near the end of the day), meaning he still had a chance to play the weekend if he could just make birdie.

But a wayward tee shot into the tall, thick heather ended any chance of that. Murphy hacked it out from there, and in one last desperate attempt to earn a tee time on Saturday, his pitch from 70 yards came to rest just two feet short.

As he waited for his playing partners to finish, Murphy crouched again, staring over at the 10th tee. There, the featured group, including some young rising stars, was starting its second round. The largest gallery of the week was gathered around the tee box and cheered enthusiastically as each player was announced. It was a harsh reminder that in just two years Murphy had gone from the feature group to a forgotten man.

After knocking in his par putt, he headed off the green. To add insult to injury, the shuttles, normally there to usher the players finishing on the 9th hole, which was a long distance from the clubhouse, were nowhere to be found. Murphy started the long walk alone, but then he saw a friend with his two young boys.

He forced a smile. The friend was unsure what to say, not that there was anything that could be said. So the two embraced. Murphy then turned his attention to the kids, taking off his hat and placing it on one of the young boys’ heads. Then he handed his glove to the other.

He then resumed the long walk to the clubhouse, his entourage and caddie giving him the space he needed. He finished the walk with his head down, his hands jammed in his front pockets.

As I stood outside the scoring area waiting, I felt uneasy, unsure of what I would say when he emerged from the small blue building.

“John, I totally understand if you don’t want to talk,” I said. “I hate to even ask, but if you are up for a quick chat…”

Murphy cut me off. “No problem, Ryan,” he said. “Unfortunately, I’m used to this.”

For 20 minutes, Murphy spoke with me as I asked questions I wish I didn’t have to ask. It may be because Murphy has always been so kind to me and so respected by his peers, but it was the most challenging conversation I’ve ever had with a professional golfer. His frustration was evident.

He spoke about how he still felt good about the direction of his game, but admitted that at this moment, it was hard to take any positives from the day. He said a couple of drives coming in were proof that his game was headed in the right direction. “I didn’t have much hope when I was finishing last in every event last year,” he said.

As we were talking, a man approached and asked if he could interrupt. He turned to Murphy, gave an explanation of their connection, and asked me to take a picture of the two of them, pushing his phone toward me. Murphy forced a smile as I snapped a couple of pics.

“Going to be around for the weekend?” the man said, oblivious to the torturous last hour and a half Murphy had spent watching the weekend slowly slip from his grasp.

“Nope, fell a couple short,” he replied. As the man walked away, Murphy turned to me and said, “Ouch, that hurts.”

I shook Murphy’s hand and thanked him for his time. Then I watched him join his family.

In the short time I’ve been writing stories, there are a few players I check on weekly to see how they are playing. John Murphy is one of those players. He is kind, considerate and talented. One day down the road, I hope to see him again putting his hands on his head in disbelief, but it’s because he is hoisting a trophy.