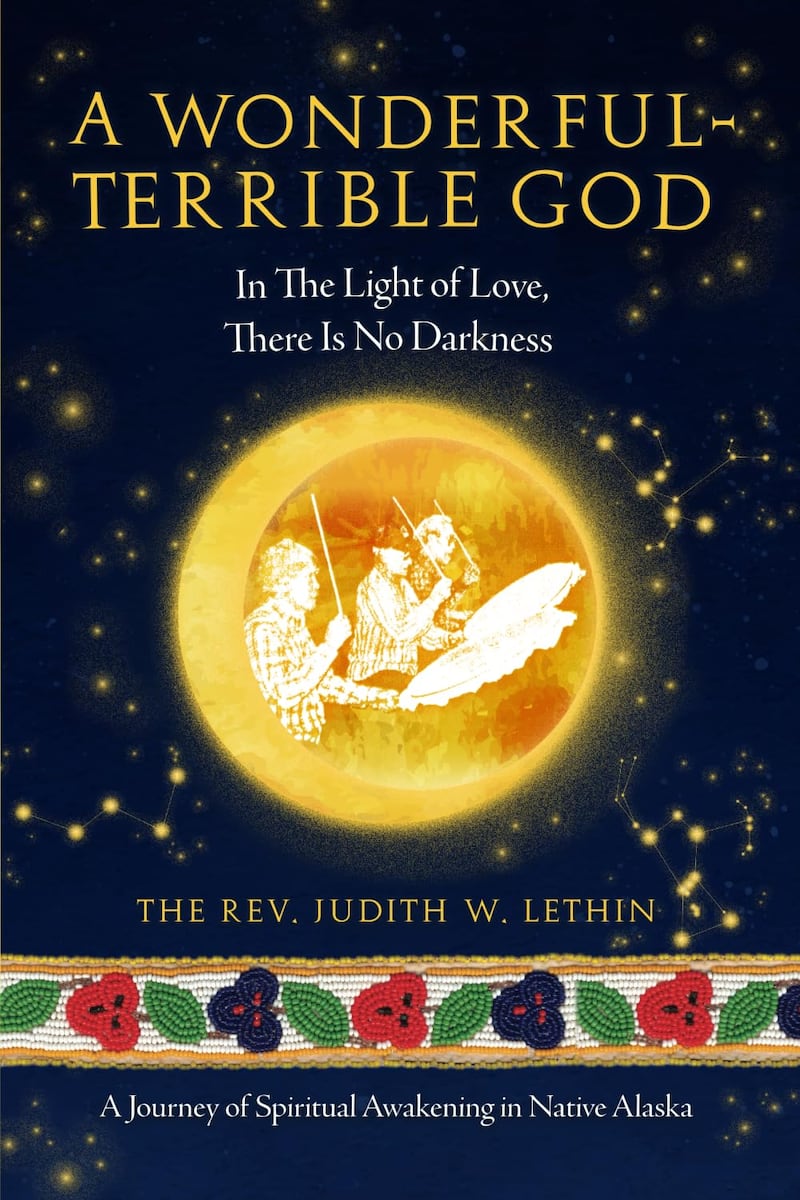

“A Wonderful-Terrible God: In the Light of Love, There Is No Darkness”

By the Rev. Judith W. Lethin; Cirque Press, 2024; 328 pages; $25.

“I’d come to San Francisco to understand and make peace with the shame-based moral issues from my own life, but really motivated me?” the Rev. Judith Lethin asks partway into her memoir. “I knew the suffering of others kept me awake at night as I recalled their stories over and over again, but what was it I was working so hard to suppress in myself?”

Lethin, who was attending a class on human sexuality, had arrived in the city from her home in Alaska carrying in her mind a list of the social ills she had encountered in her experiences working for the Episcopal Church in rural Alaska. Similar anguishes had afflicted her and members of her family during her childhood, leaving her with lasting scars. Sexual and physical abuse, alcoholism, emotional and body shame, intergenerational trauma, fear of abandonment and more; events and their consequent emotional responses that, she indicates, manifested themselves in a “volatile temper and larger-than-life personality.”

These are among the regions in herself and others that Lethin explores and finds redemption from in her memoir, “A Wonderful-Terrible God.”

Lethin is an Episcopal priest whose adult work both before and after her ordination has mostly taken place in Native communities, and primarily in the Lower Yukon Athabascan villages of Anvik, Shageluk and Grayling.

The book is a wandering collection of essays that offer snapshots of her life, which began in rural Idaho in a family that offered her both the freedom to roam and the chance to acquire a sense of independence and self-sufficiency, even as inescapable ancestral demons led her into overeating and early alcohol consumption.

By adulthood she was living in Alaska and heavily involved with church activities. During the 1970s and into the ’80s, her husband ran a large and successful business, allowing her to raise their four children and engage in volunteer work. It all came to a shattering halt during the steep economic downturn that swept over the state late in the ’80s, forcing an asset sale for the suddenly faltering business and a move from their comfortable home in Anchorage to a basic family cabin in Seldovia.

There Lethin, despite no real qualifications, was hired to oversee an alcohol recovery program, which directly exposed her to the ravages of alcoholism on both white and Native victims, as well as to confront her own addiction, which, like so many others do, she had kept hidden.

This episode, along with her childhood tribulations, lent her insight and compassion into the troubles she would encounter as her church work took her ever more frequently into Native villages. But it also left her unsure what to say or do to assist others.

The first half of the book weaves back and forth between her early years in Alaska and her vivid childhood memories. Her father earned his living through self-employed hard labor while her mother, widowed from her first marriage, owned and operated a movie theater. Both were remote, and Lethin never really knew parental love and acceptance.

This absence has echoed throughout her life, and as she began her work in the villages, she witnessed similar inter-familial relationships, compounded by far too many early deaths.

But she found something else as well. A culture that, unlike much of mainstream America, values its elders, who pass down to the children and grandchildren the lessons learned from their own elders, as well as those garnered from their lives.

Lethin is honest about the starkly divided legacy of Christianity on Alaska Natives. For the most part, it was not so much introduced to them as imposed, causing tremendous cultural upheaval. It also led to the sickening abuse that transpired in church-run boarding schools that Native children were forced to attend for decades, abuse that continues to reverberate through Native communities.

However, Alaska Natives by and large embraced the religion, and over the course of a century or so, revived their own traditions and blended them with their Christianity rather than reject the latter and fully return to the former.

Lethin learned not just to recognize the value in this, but to apply its lessons to her own faith. Somewhere along the way — it almost seems ingrained in her — she found listening more productive than talking. The teacher, there to guide others in their spiritual lives, became the student, there to learn how to live spiritually.

The second half of the book recounts a series of visits she made to villages during times of death. Unable to find what to say amid tragedies that villagers had to confront both through their adopted faith and ancient practices, she realized by the example of others that words are not and never can be enough to ease the suffering of those left behind. What matters is simple presence. To never abandon the grieving. Neither in the immediate aftermath of the death, nor many years later when the unceasing pain remains. The words of Christ, “I was sick and you looked after me,” apply not just to physical ailments, but even more so to internal distress.

There are some curious omissions in this book. Lethin largely bypasses or minimizes key moments in her life, including much of her education, her many substantial accomplishments listed in the brief biography in the back, the nuts and bolts of becoming a priest, and perhaps most perplexing of all, how her faith initially developed, and what held her there.

But perhaps these are of minimal importance. This is a soul’s journey, not a life story. And the destination this brought her to is found in the final chapter. Lethin attends the passing of her close friend Katherine Hamilton, an elder from Shageluk who lost her son to suicide and young grandson to drowning. As Hamilton lies in bed, succumbing to cancer, Lethin fully absorbs the lesson she has learned from her, that one must be “loving people like she loved people, unconditionally, even though she knew all about them.”

[Book review: Anchorage man tells his story of redemption in memoir]

[Book review: Indigenous voices reflect on knowledge and value systems]

[For a different outlook on ‘prepping,’ Bill Fulton and Jeanne Devon collaborate again on new book]