For the first time in 111 years, items once belonging to the late Albert Mullins were back in the hands of his family members thanks to the detective work of one Montreal historian.

Wearing white cotton gloves, Caroline Mullins from Bournemouth, England held a dollhouse furniture set, travel mementos and flipped through an album containing scraps of paper from her great uncle — who, for much of her life, had remained a mystery.

She was never told about his successful instrument business, travels abroad with his wife and daughter or even that he was one of the 1,012 people killed on board the Empress of Ireland when it sank off the coast of Rimouski, Que., in 1914.

“I didn’t know them,” said Caroline, her eyes welling with tears. “But well, it’s still very personal, isn’t it?”

David Saint-Pierre and Mullins looked at artifacts from the shipwreck. She connected with Saint-Pierre after he published an article about the items. (Société d’histoire du Bas-Canada)Tracing back items to owners ‘extremely rare’

David Saint-Pierre and Mullins looked at artifacts from the shipwreck. She connected with Saint-Pierre after he published an article about the items. (Société d’histoire du Bas-Canada)Tracing back items to owners ‘extremely rare’

Unravelling her relative’s story started when she stumbled upon a 2023 article by Montreal historian David Saint-Pierre.

He had written about recently obtained items from the wreck connected to a man named Albert Mullins. Six months later, Saint-Pierre received a Facebook message from Caroline.

“She decided right away that she wanted to cross the ocean and come see the artifacts,” he said, which were being transferred to Quebec’s Société d’histoire du Bas-Canada.

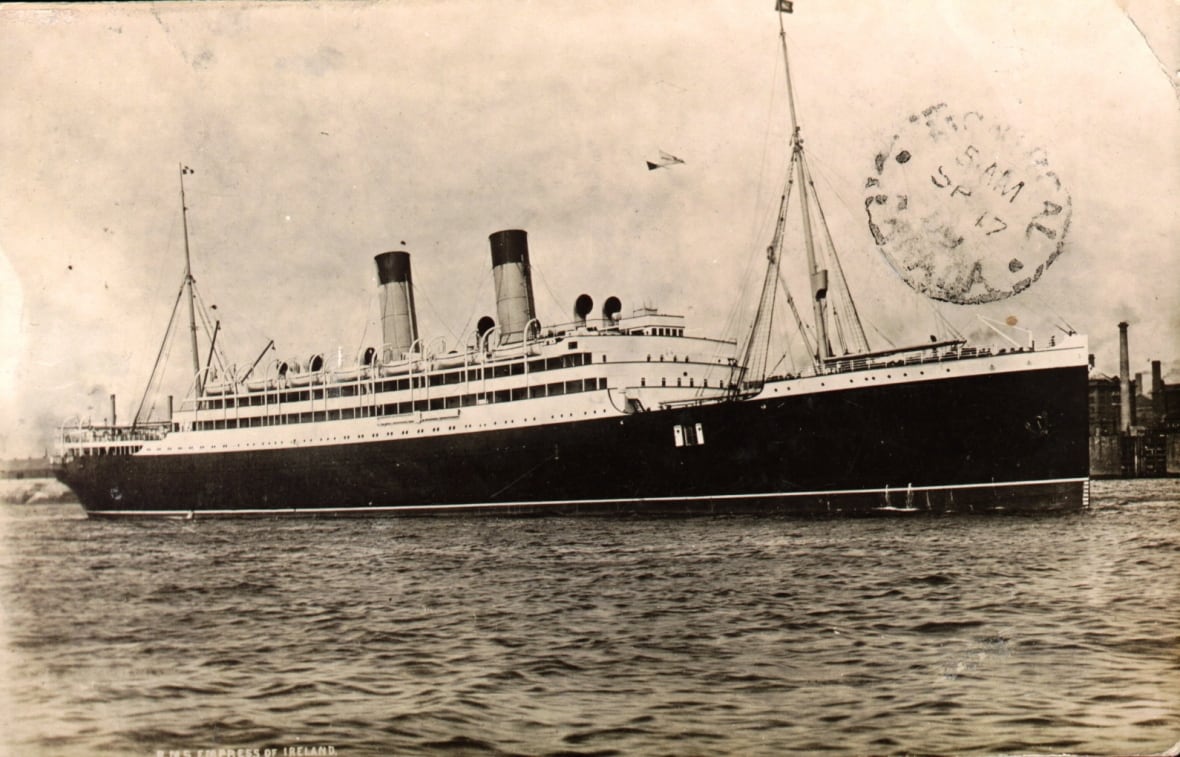

The Empress of Ireland is shown in an undated photo. The Canadian Pacific steamship collided with a Norwegian freighter near Quebec on May 29, 1914, sinking in 14 minutes and killing 1,012 people. (Site historique maritime de la Pointe-au-Père)

The Empress of Ireland is shown in an undated photo. The Canadian Pacific steamship collided with a Norwegian freighter near Quebec on May 29, 1914, sinking in 14 minutes and killing 1,012 people. (Site historique maritime de la Pointe-au-Père)

“It’s extremely rare that we get the occasion, the opportunity to trace back items directly to their owners. So I don’t think it will happen often again.”

He says it might be the only example of items recovered from the shipwreck that could be traced back directly to one single passenger. They’re being preserved and kept in a bunker, near Montreal.

The items were originally found and recovered in 1986 in a canvas bag by a diver who dove the site 206 times, but rarely entered the ship’s baggage room during his dives, says Saint-Pierre.

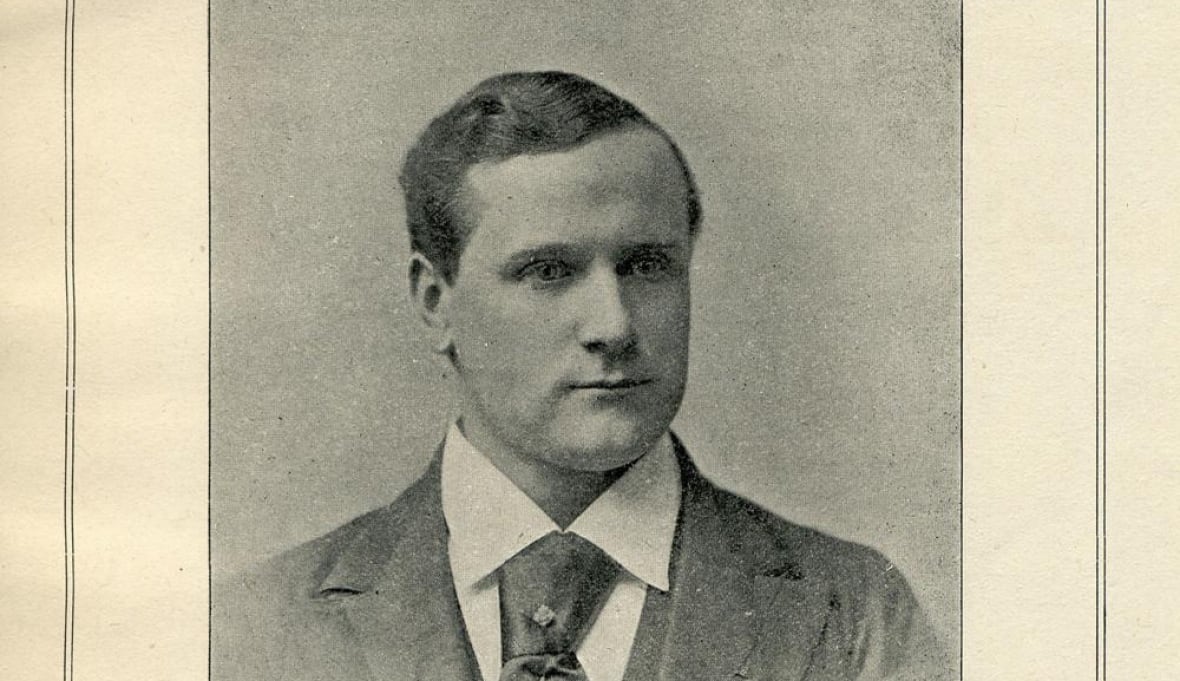

Albert Mullins died on board the Empress in 1914. A historian in Montreal helped trace items recovered from the shipwreck back to him. (Barnes and Mullins Ltd./Submitted by David Saint-Pierre)

Albert Mullins died on board the Empress in 1914. A historian in Montreal helped trace items recovered from the shipwreck back to him. (Barnes and Mullins Ltd./Submitted by David Saint-Pierre)

On one trip, he picked up what would later be identified as Mullins’s items — drying and storing the materials for decades before they changed hands to Guy D’Astous, who owns a private collection and is the collection director at the Société d’histoire du Bas-Canada.

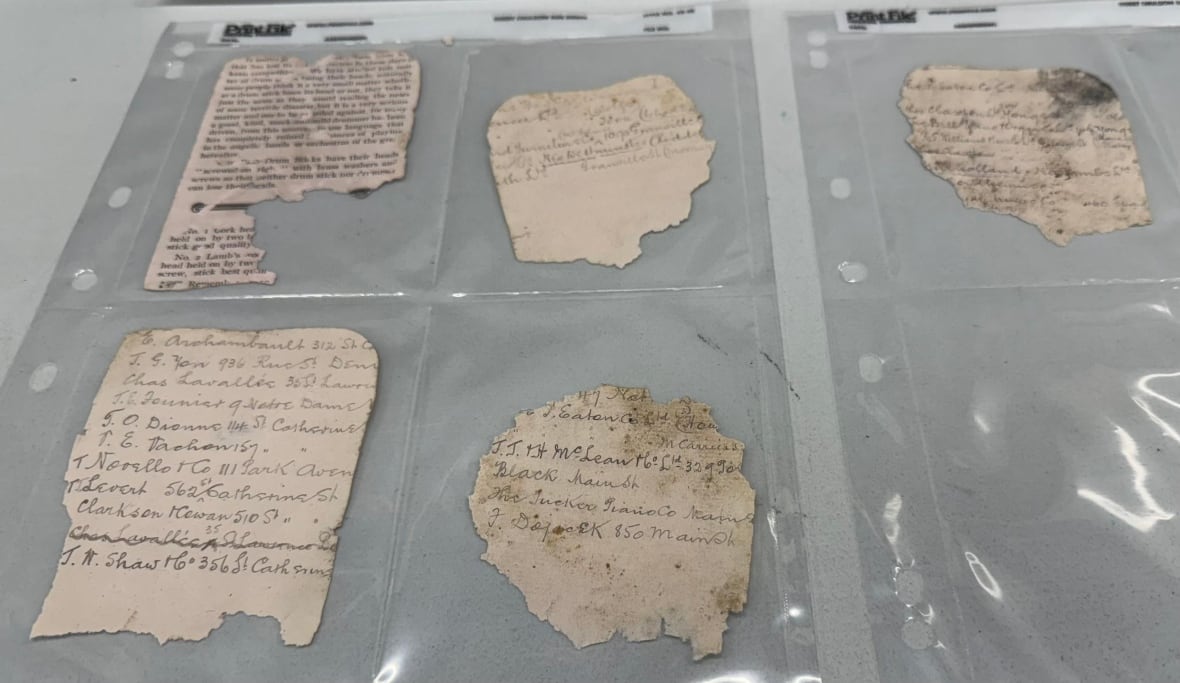

In 2023, Saint-Pierre laid eyes on the scraps of paper organized in a photo album and started to connect the dots. It included the name of instrument stores — and Saint-Pierre knew why.

David Saint-Pierre compared a writing sample from Albert Mullins to the scraps of paper found in the collection from the shipwreck. He said it confirmed the notes belonged to the late father of two. (Société d’histoire du Bas-Canada)

David Saint-Pierre compared a writing sample from Albert Mullins to the scraps of paper found in the collection from the shipwreck. He said it confirmed the notes belonged to the late father of two. (Société d’histoire du Bas-Canada)

“Doing research on the Empress for so many years, there are a few passengers that we begin to know, and I knew of Albert Mullins,” said Saint-Pierre.

“I started having thoughts that it could be related to Albert.”

“It gives special significance to what I do,’ says historian

At the time of his death, the man in his 40s, had been had been travelling 18 months and was heading back home to England on the Empress in first class when the Canadian Pacific steamship collided with a Norwegian freighter — sinking in 14 minutes.

In 1986, a diver picked up what would later be identified as Mullins’s items — drying and storing the materials for decades before it changed hands. (Société d’histoire du Bas-Canada)

In 1986, a diver picked up what would later be identified as Mullins’s items — drying and storing the materials for decades before it changed hands. (Société d’histoire du Bas-Canada)

Both Mullins and his young daughter died, while his wife sustained two broken legs and returned to England months after her recovery to rejoin their son back home.

Mullins had been a successful businessman before his death, founding and operating Barnes and Mullins instrument wholesaler — still in business today. When Saint-Pierre got a glimpse of the handwritten notes detailing music and book shops, he reached out to the British company to supply a writing sample from Mullins.

Caroline Mullins held doll furniture that was discovered in Albert’s possessions, likely belonging to his daughter, who also died on board. (Société d’histoire du Bas-Canada)

Caroline Mullins held doll furniture that was discovered in Albert’s possessions, likely belonging to his daughter, who also died on board. (Société d’histoire du Bas-Canada)

“And it confirmed 100 per cent of the scraps of papers were his, because he had a quite particular and peculiar handwriting, especially the Fs and the Es were unmistakable,” said Saint-Pierre.

“I really like that feeling of seeing the research fall into place and be useful and touch people and it makes it personal. It gives special significance to what I do because otherwise, it would be just objects.”

The bodies of Mullins and his daughter were never recovered, and Caroline says she brought her daughter on the trip to Quebec as a way to pay their respects for the accident sometimes referred to as the “forgotten tragedy.”

“The purpose of us coming here is that we wanted to connect to it,” she said. “We didn’t want it to be forgotten within the family.”