The first national tour of the musical Parade arrived in Chicago this week with impressive credentials. Based on a true story set in Atlanta, it involves the 1913 rape and killing of a 13-year-old girl in the basement of the pencil factory where she worked. The musical’s focus is on the main suspect: Leo Frank, the factory’s manager. He’s Jewish and a recent Brooklyn transplant. Frank is arrested and charged with the crime. Although his sentence is later reduced from the death penalty to life imprisonment, a few local townsfolks have something else in mind.

As for the musical’s credentials, Parade was written in 1998 by two-time Tony Award winner Alfred Uhry (Driving Miss Daisy), with music and lyrics by three-time Tony Award winner Jason Robert Brown (The Last Five Years). Furthermore, it was co-conceived by 21-time Tony Award winner Harold Prince and directed by two-time Tony Award winner Michael Arden (Maybe Happy Ending). A 2023 Parade revival, featuring Ben Platt (Dear Evan Hansen), won a Tony for the Best Revival of a Musical and two others for its music.

That’s pretty heady stuff. in musical theater terms. And yet, even with the absolutely brilliant production now onstage at the CIBC Theatre, one still can’t recommend this show for everyone. For those seeking escapism in theater, who want everything tied up with a bow (and a smile) at the end, this show isn’t for you. Its unflinching gaze at history tells a story that must be told, even if it isn’t easy to watch.

As Leo Frank (center), Max Chernin proclaims his innocence in Parade. Photo by Joan Marcus.

As Leo Frank (center), Max Chernin proclaims his innocence in Parade. Photo by Joan Marcus.

Compelling Historical Moments Wrapped in a Musical

Parade captures a low point in American history, where antisemitism, racism, misogyny and an inflated sense of regional pride ran rampant. No, we are not talking about life in America, circa 2024. Parade covers the years immediately following the Civil War, when those who fought for the Confederacy refused to admit defeat.

The musical begins almost 50 years before Leo Frank’s conviction. To the rat-a-tat sound of a military snare drum, a young Confederate soldier (Trevor James), begins to sing a beautiful song, “The Old Red Hills of Home.” Soon he is joined by a much older, war-hobbled version of himself (Evan Harrington), as the entire community chimes in. The chorus is accompanied by those waving Confederate flags, and it soars and swells as the townsfolk sing their ode to the antebellum South, when the land “was free” (pre-Civil War). It’s horrifying and beautifully staged, all at once.

The musical is peppered with historical facts, almost to its detriment. It picks up steam with Frank’s arrest, then moves on to his trial. Two years later, when legal appeals have been exhausted, Frank wakes up one day to discover that then-governor John M. Slaton (an excellent Chris Shyer) has commuted his sentence to life in prison. Some of the enraged townsfolk decide to “set things right” and drag Frank out of jail. They promptly lynch him, as the original verdict demanded.

Parade is rarely performed, and it’s easy to see why. Bold newspaper headlines of Frank’s lynching, viewed on a large backscreen, appear before the show even begins. That removes the element of suspense. Also, Arden’s staging is more presentational than representational. There’s a long, raised platform onstage, and this is where most of the action takes place. Often, characters are seen walking up a short staircase to the platform before delivering their lines. The effect can be slightly off-putting for audiences, as if they are watching a school pageant being performed.

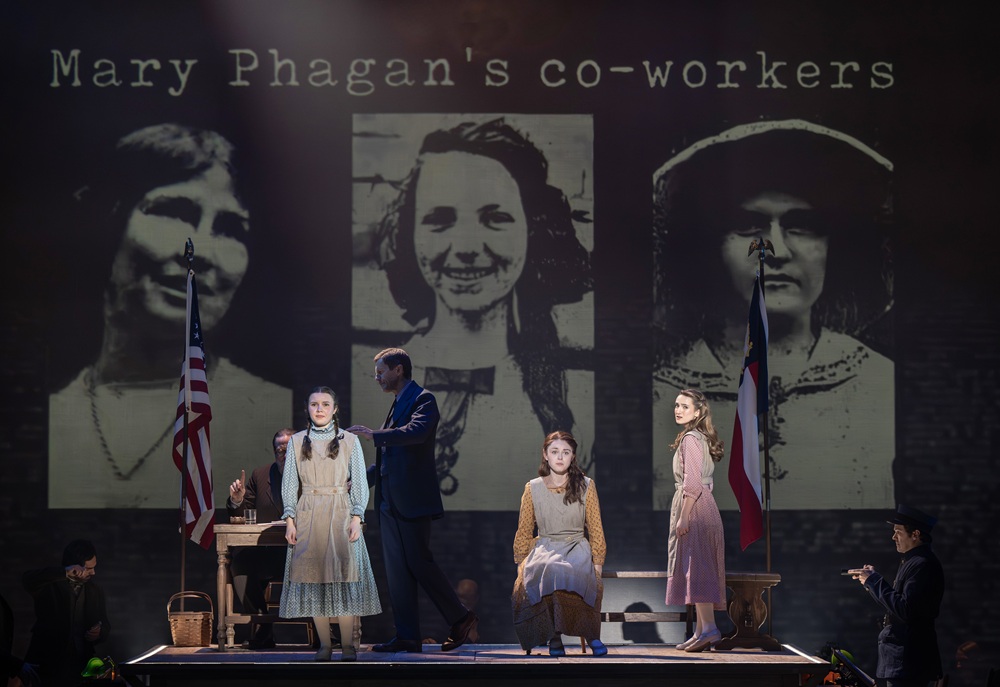

Several factory workers who befriended co-worker Mary Pfagan take the stand in the trial of Leo Frank. Photo by Joan Marcus.

Several factory workers who befriended co-worker Mary Pfagan take the stand in the trial of Leo Frank. Photo by Joan Marcus.

A Large Cast Delivers a Full and Satisfying Story

The show’s emphasis on its many characters prevents audiences from diving more deeply into the lives of Leo (Max Chernin) and his wife, Lucille (Talia Suskauer, both excellent). Lucille was raised in Georgia, and her family owns the factory that employs Leo. Over the years, Lucille has come to accept the town for what it is. She doesn’t chafe at local customs the way her husband does. His own blindness—in terms of constantly defining himself as “an outsider”—will cost him more than he ever suspects. It’s evident in his attire (costumes by Susan Hilferty and Mark Koss), his behavior (a businesslike approach to basically everything), his advanced education and his sense of superiority.

Frank is surprised and astonished at the speed of his arrest, which is based on the flimsiest evidence imaginable. The arrest itself is orchestrated in a secret meetiing between two politicians. One surmises that, this time, “hanging another Nigra ain’t enough. We gotta do better.” One of the men, prosecutor Hugh Dorsey (Andrew Samonsky) is ordered to make Frank the number one suspect in the girl’s killing.

In addition to Dorsey, other corrupt officials seek to improve their career prospects from the trial. The same goes for the local media, represented by a sleazy. day-drinking reporter (Brian Vaughn). His right-wing publisher, Tom Watson (Griffin Binnicker), also seeks publicity through his crusade against Frank. While this sequence may not rivet audiences, it was very important in establishing motives. It should be noted that the story has a personal connection to co-creator Alfred Uhry, who was raised in Atlanta. Uhry’s great-uncle owned the pencil factory in which Frank worked.

Arden, as the show’s director, uses a large background screen to depict photos of the actual people who are represented in the musical. Perhaps the most effective use of this technique is when three young pencil factory employees, all friends of the ill-fated Mary Phagan, chime in with identical stories to incriminate Frank. It culminates in a powerful song, “The Factory Girls.”

Lucille (Talia Suskauer) and Leo Frank (Max Chernin) express their love for each other. Photo by Joan Marcus.

Lucille (Talia Suskauer) and Leo Frank (Max Chernin) express their love for each other. Photo by Joan Marcus.

Beautiful Score Sets the Tone for An Unequaled Theatrical Experience

Another scene stealer is the Act II opener, “A Rumblin’ and a Rollin,” in which two of the governor’s Black employees, Riley (Prentiss E. Mouton) and Angela (Oluchi Nwaokorie), use dark humor to describe their feelings about all the national attention this trial attracts. As one notes: “there’s a Black man hanging in every tree,” and “what if (the victim) was a little Black girl?”

If Parade is based on historical fact, it rises to another level on a gorgeous score by Jason Robert Brown. In a way that’s reminiscent of another musical, Ragtime, the songs add meaning and depth to the characters. The singing talent here is amazing. It goes far beyond the main characters to include the factory’s night watchman (Robert Knight) and factory janitor Jim Conley (Ramone Nelson). It helps that the first national tour cast includes seven of the Broadway revival cast members.

One of Parade’s most lasting stories is that of Lucille Frank, who is awakened to her town’s bigotry by her husband’s arrest. She pushes herself beyond the boundaries of wifely household duties to take action on her husband’s behalf. Her persistence stuns Leo, and it even surprises her (told deliciously in the song, “This Is Not Over Yet”). That the two fall in love (perhaps for the first time) in the final moments of their marriage gives Parade its heartbeat.

Parade plays through August 17 at the CIBC Theatre, 18 W. Monroe St. Tickets are available at www.broadwayinchicago.com. The show runs 2 hours and 45 minutes, with one intermission.

For more information on this and other productions, see theatreinchicago.com.

Did you enjoy this post? Please consider supporting Third Coast Review’s arts and culture coverage by making a donation. Choose the amount that works best for you, and know how much we appreciate your support!