Tropical Storm Erin has begun what’s expected to be a week-plus oceanic journey across the North Atlantic. As it looks now, much of that trek will be as a potent hurricane that bears close watching.

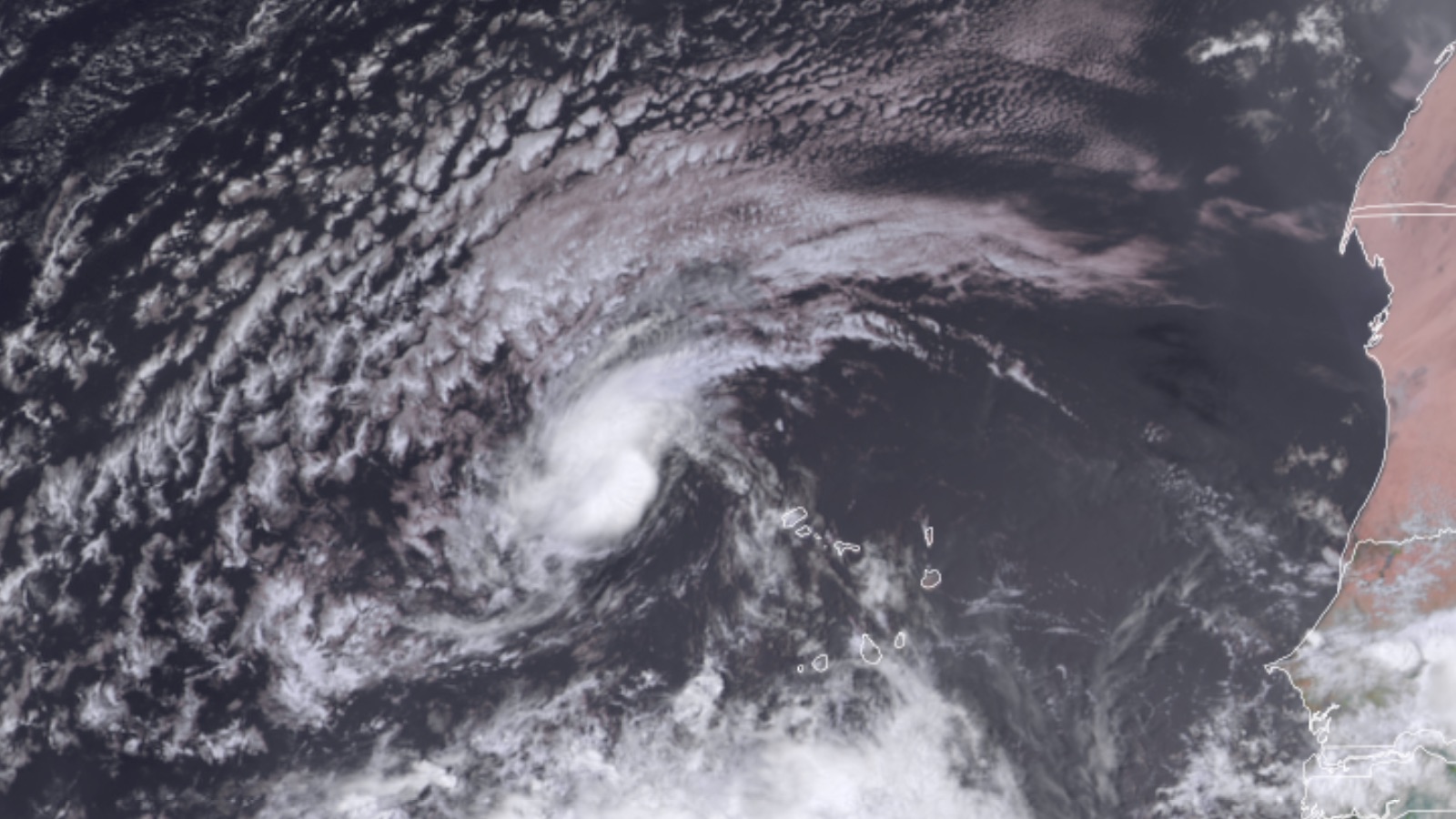

Erin was designated a tropical storm on Monday after it barrelled across the Cabo Verde Islands on Sunday as a strong disturbance. As of 11 a.m. EDT Monday, Erin was centered nearly 300 miles west-northwest of the Cabo Verde Islands, heading west at a brisk 20 mph. Erin’s sustained winds were 45 mph.

Over the period 1990-2020, the average formation date of the Atlantic’s fifth tropical storm of the year was August 22, so the Atlantic is running a bit on the high side in terms of named-storm production – but all of the named systems to date have been only weak to moderate tropical storms. The average formation date of the first Atlantic hurricane is August 11, and current forecasts bring Erin to hurricane strength on Wednesday, August 13.

On Monday, Erin had a small but well-defined circulation, as detected by wind data from a satellite-borne scatterometer. Wind shear is light to moderate (around 10 knots), and the atmosphere is on the moist side, with mid-level relative humidity of around 60 percent. Emerging tropical systems often benefit from nighttime processes that help showers and thunderstorms to blossom – the so-called nighttime convective maximum – and this boosted Erin’s development on Sunday night. Also working in Erin’s favor is general rising motion across the eastern tropical Atlantic, the result of multiple large-scale features aligning (see our August 8 post).

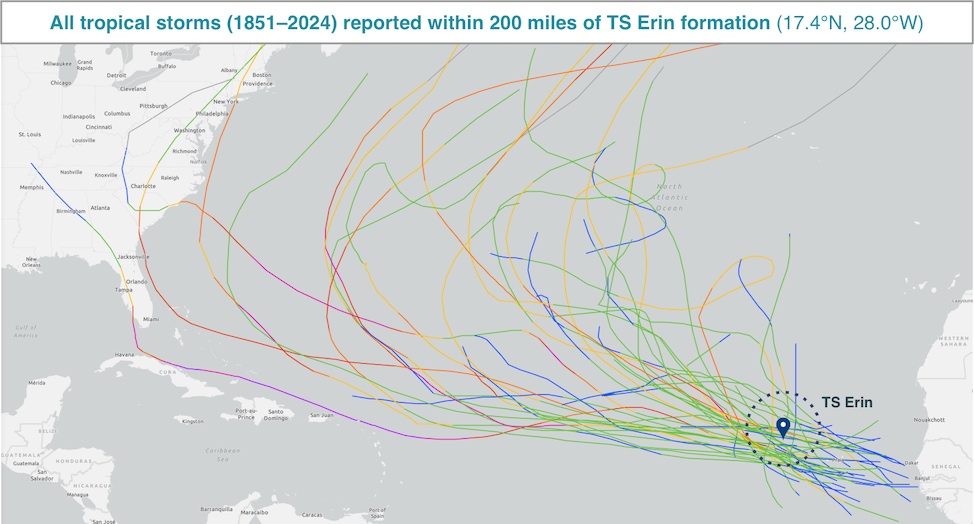

Figure 1. Over the past 174 years, a total of 41 Atlantic systems (tracks shown) developed or passed within 200 miles of Erin’s formation spot while at tropical-storm or hurricane strength. (Image credit: NOAA Hurricane History)

Figure 1. Over the past 174 years, a total of 41 Atlantic systems (tracks shown) developed or passed within 200 miles of Erin’s formation spot while at tropical-storm or hurricane strength. (Image credit: NOAA Hurricane History)

Erin gets a head start

Geographically speaking, Erin is off to an early start. Tropical waves moving off West Africa are among the most common seeds for Atlantic development, but it can take days for these to organize, as sea surface temperatures (SSTs) in the far eastern Atlantic are often on the cool side for development. SSTs beneath Erin on Monday were close to average for this time of year at about 26 degrees Celsius (79 degrees Fahrenheit), which is considered the minimum for supporting tropical storm formation.

As shown in Fig. 1 above, in the 174 years of NOAA’s Atlantic hurricane database, only 41 tropical storms have developed or moved within 200 miles of Erin’s initial location (latitude 17.4 north, longitude 28.0 west). The most recent of these was Hurricane Margot in 2023, which moved harmlessly across the central North Atlantic. Most of these systems – but not all of them – ended up recurving northward through the Atlantic without affecting any of the Caribbean islands or North America (and none of them actually entered the Caribbean).

The two most powerful storms in recent decades that formed close to Erin’s birthplace each inflicted tens of billions in U.S. damage and took at least 50 lives.

- Florence (2018) weakened from cat 4 to cat 1 strength before landfall, but still caused catastrophic flooding in North Carolina.

- Irma (2017) was the first hurricane on record to hit the northern Leeward Islands at cat 5 strength, and it became Cuba’s costliest storm on record. Irma reached the Florida Keys at cat 4 strength and weakened as it churned north along the western Florida peninsula, causing widespread devastation.

The other two significant hurricanes affecting the U.S. in Fig. 1 are Gloria (1985), which weakened from Cat 4 strength before striking Long Island, New York, at Cat 1 strength, and the Sea Islands Hurricane (1893), which took at least 1000 lives with its unusual landfall as a Cat 3 storm near Savannah, Georgia, bringing massive surge into Georgia and South Carolina.

Forecast for Erin: A powerhouse storm on a classic North Atlantic track

There’s unusually strong agreement among forecast models that Erin will likely intensify this week into a major hurricane by the weekend and will continue to rage well into next week. Erin will encounter progressively warmer sea surface temperatures (SSTs) as it moves mainly west over the next several days into the central tropical Atlantic. SSTs along Erin’s path will be around 28°C (82°F) by Thursday and possibly as high as 29°C (84°F) by Saturday.

Erin will encounter deeper oceanic heat content as it approaches the western North Atlantic early next week, as well as SSTs running about 1°C (2°F) warmer than average for mid-August.

Invest #97L has developed into Tropical Storm #Erin. As noted by @pppapin.bsky.social in the Advisory 1 forecast discussion from NHC, the ocean near Erin isn’t all that warm (26-27°C) but warmer waters lie ahead of the newly-minted tropical cyclone (TC).

— Kim Wood (@drkimwood.bsky.social) 2025-08-11T15:23:50.939Z

Wind shear will remain light to moderate over Erin for the next several days, and the surrounding atmosphere should remain fairly moist. Wind shear may increase late in the week before relaxing by the weekend, so it’s possible Erin’s intensification will briefly pause. On the flip side, Erin is a fairly small system for now, so it could both strengthen or weaken quickly. The National Hurricane Center’s initial forecast for Erin was for gradual strengthening, reaching hurricane strength by Wednesday and Category 3 strength (major hurricane) by Saturday.

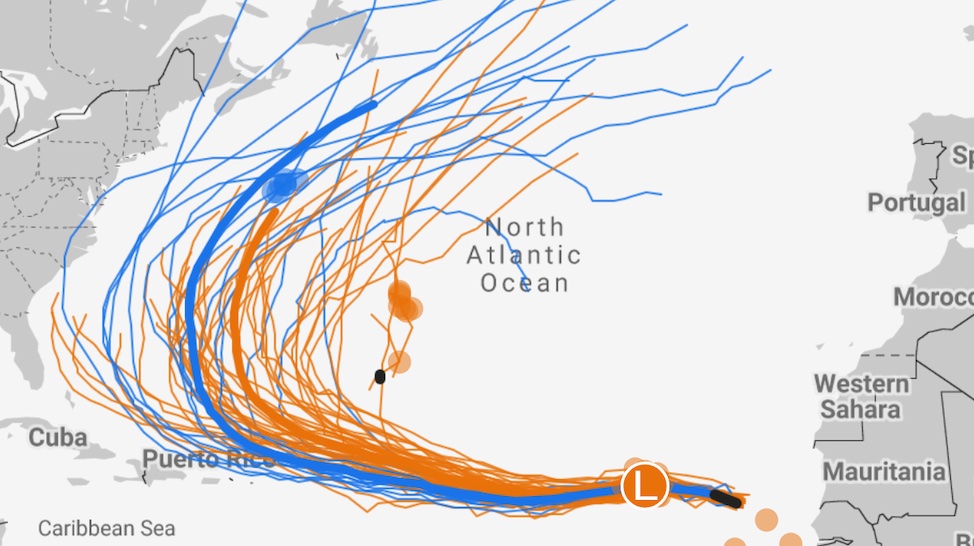

As of Monday, multiple ensemble models were in close agreement that Erin is much more likely to recurve east of North America than to move onto the U.S. East Coast (see Fig. 2). This is because an upper-level trough that could “pick up” Erin is predicted to be moving across the northeast United States and eastern Canada into the North Atlantic.

Figure 2. Ensemble model tracks for Erin generated from a starting point (east end of tracks) at 0Z Monday, August 11, 2025 (8 p.m. EDT Sunday). The European model ensemble is in orange; the experimental Google AI tropical model ensemble is in blue. The dark blue and dark orange denote the mean solutions from averaging each of the ensembles. (Image credit: Google Weather Lab)

Figure 2. Ensemble model tracks for Erin generated from a starting point (east end of tracks) at 0Z Monday, August 11, 2025 (8 p.m. EDT Sunday). The European model ensemble is in orange; the experimental Google AI tropical model ensemble is in blue. The dark blue and dark orange denote the mean solutions from averaging each of the ensembles. (Image credit: Google Weather Lab)

Nearly all members of the Sunday-evening and Monday-morning European and GFS model ensembles, as well as the experimental Google AI tropical model ensemble, recurve Erin sharply to the north and northeast, potentially affecting Bermuda, after the storm makes a sharp right turn somewhere just north of the Leeward Islands.

An important caveat: any such recurvature wouldn’t even begin until a week from now — far enough out that the predicted steering currents could change in subtle but important ways. For the time being, the strong agreement both within and among ensembles is a positive sign, but it’ll be critical to watch for any wholesale shifts among the ensembles over the next several days.

Assuming that Erin intensifies into a prolonged hurricane as predicted, we can expect it to produce days of large swells leading to high surf, coastal erosion, and dangerous rip currents along a large swath of the Atlantic coast of North America, as well as north-facing coasts of the Greater Antilles islands.

Putting aside the current atmospheric steering… What are the chances a storm like #erin hits the US starting from its current position (red TS symbol on bottom right) on the north side of the Cape Verde Islands? Answer: Low (purple) less than 10%, based on historical probabilities. So it’s rare 1/

— Jeff Berardelli (@weatherprof.bsky.social) 2025-08-11T16:54:13.640Z

Erin is expected to be the only system of major concern in the Atlantic for at least the next week. In the 2 p.m. Monday Tropical Weather Outlook from NHC, two weak systems in the central North Atlantic were each given only 10 percent odds of modest development over the next two days. A disturbance off the central Gulf Coast was assigned near-zero odds, although it could produce pockets of 2 to 4 inches of rain in the western Florida panhandle early this week.

Jeff Masters contributed to this post.

Republish This Story

Republish our articles for free, online or in print, under a Creative Commons license.