Tech entrepreneur John Lauer wants to bring the speed and efficiency of Shenzhen’s electronics ecosystem to the United States—without the trip to China. His aim is to solve what he calls a fundamental time problem: what takes minutes in software development can take months in hardware engineering.

Lauer describes his latest venture, Adom Industries, as what he calls the world’s first cloud-connected electronics prototyping factory. “Think of it as a data center, but for atoms, not bits,” he said in an interview with Dallas Innovates. “It’s a fundamental shift in how electronics get built.”

The “cloud factory” is designed to give engineers remote access to an ecosystem with the advantages of Shenzhen—a global hub for electronics manufacturing—without leaving their desks.

In practical terms, that means a virtual electronics workbench in the cloud linked to a connected factory with advanced logistics. Lauer is building Adom so engineers anywhere can design, prototype, and test hardware “from the comfort of their laptops” in its programmable AI cloud lab, while connected robots produce a prototype in near real time and ship it overnight, he said.

His global vision now intersects with a local decision point.

On Aug. 12, the Fort Worth City Council will vote on a $15 million performance-based incentive package for Adom Industries’ planned headquarters-and-factory.

Code-named “Project Nimbus,” the $229 million, four-phase development would bring 267 high-wage jobs and more than $240 million in research and development over 15 years. Economic development official Kelly Baggett said it would be among Fort Worth’s most significant semiconductor-related projects to date.

Adom is currently operating from the AllianceTexas development in north Fort Worth.

While Fort Worth is a contender for the project, Lauer said other sites remain in play for strategic reasons—including Arizona’s proximity to the new Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. fab—with Tennessee and Oklahoma also competing for the factory.

“This will be one of the most high-tech factories in the world,” Lauer said.

From a $952 million exit to building Adom

“This will revolutionize the electronics prototyping and design industry,” Lauer said. His track record of firsts—and big exits—suggests he knows the territory

Foreshadowing the cloud-connected manufacturing model he’s building today, Lauer pioneered advances in CNC control—a capability central to Adom’s vision. His 2013–2014 work on the open-source platform ChiliPeppr made the technology more accessible and affordable. It was the first to let users run CNC machines from a web interface, laying the groundwork for more sophisticated solutions now emerging.

Earlier, as co-founder of Simplewire in 2002, Lauer helped develop one of the first SMS and mobile payment platforms, giving Twitter its first short code and opening the door for other early mobile communications breakthroughs.

Then, at Zipwhip, co-founded in 2007, Lauer and his team invented the toll-free texting industry—text-enabling 44 million toll-free numbers—and pioneered business landline texting, allowing companies to send and receive messages from their existing phone numbers. The innovation helped make text a core channel for customer alerts, from dentists’ offices to pizza chains.

Zipwhip’s 2021 sale to Twilio was one of the largest acquisitions in Seattle startup history at the time. While most outlets reported the deal at $850 million, the “closing calculated price” of the 50% stock deal was actually $952 million,” according to Lauer.

The $850 million figure reported in the press was based on Twilio’s share price at the time of the announcement, he says. But the deal required approvals from four major carriers—AT&T, Verizon, T-Mobile, and Sprint—as well as the SEC. The wait “was a risk,” but the 90-day window gave Twilio’s stock time to rise significantly, he says.

“It took about 90 days, and during that time, the stock price went up … the closing calculated price when the deal finally closed was $952 million,” he said. “Had it been a 100% stock deal … it would have been a $1.05 billion exit.”

Adom, he says, “should be even bigger.”

John Lauer, co-founder and CEO of Adom Industries, moved from Seattle to North Texas after selling Zipwhip for nearly $1 billion. [Photo: Michael Samples]

Moving to Texas with a model “nine years in the making”

Lauer invested $10 million of his own capital to seed Adom Industries. “It’s an expensive proposition, because we do have to build a factory along with software,” he said.

About three years ago, Lauer moved his family from Seattle to 54 acres in Argyle, north of Fort Worth—a relocation he calls strategic. “I opened up Google Maps and started looking around at states,” he said. “I was looking for a large warehouse district, and Alliance stood out.”

In Dallas-Fort Worth, Lauer saw a rare combination: proximity to logistics hubs like DFW and Alliance airports and cheap electricity.

But the move wasn’t just about infrastructure. “It’s also the pro-business community,” Lauer said. He noted that, while the West Coast has a deep startup culture, he sometimes encountered a kind of “anti-culture” that could create friction.

He also wanted to recruit “the top brains” in the country—from schools like MIT, Stanford, Georgia Tech, Carnegie Mellon, and UT Austin. “We have to be in a city they’re willing to move to. So far, that’s been a great success for us,” he said.

“We’ve gotten a lot of folks to move here straight out of college… I think part of it’s just the excitement of the brand of Texas these days.”

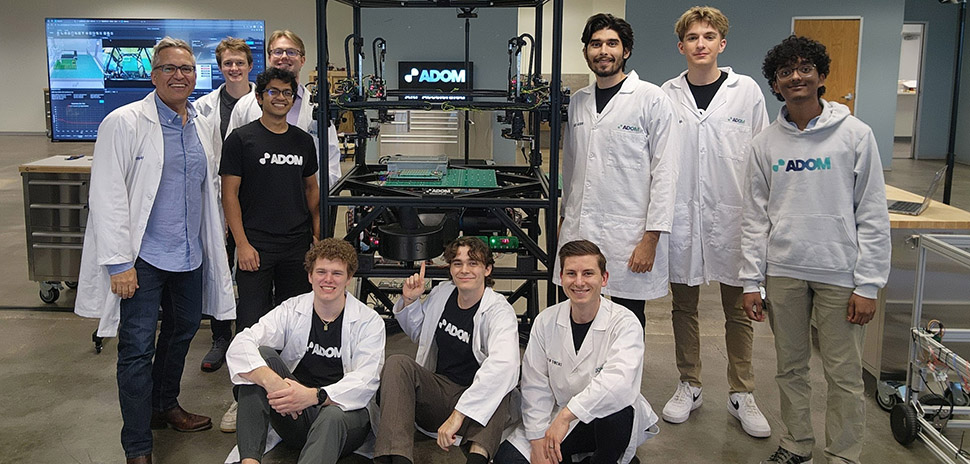

The ideas behind Adom Industries have been “nine years in the making,” Lauer says, but the company didn’t formally begin until early 2024. “We’re at 11 people now,” he said, noting that early employees hold stock positions. “I’ve been assembling essentially co-founders for the last year.”

The company’s model is split evenly between software and hardware, Lauer says—a mix many in venture capital are still figuring out how to fund. “We’re sort of a 50% software company, 50% hardware company,” he said. That full-stack complexity—combining hardware, software, AI, robotics, and physical infrastructure—is part of what excites him.

“We will become the de facto design and prototyping platform for the electronics that run your life, like your future AI self-driving lawnmowing robot, industrial equipment, healthcare devices, and even defense industry applications such as new drones,” he said.

To support growth, Adom is seeking $20 million from the Texas Semiconductor Investment Fund and $10 million from the National Science Foundation.

Lauer says a public launch is likely in 2026. While the company has made headlines recently over Fort Worth’s incentive package, Lauer makes it clear, “We’re still in stealth mode,” citing the intensive R&D required to make the factory a reality.

Building the cloud factory future: Tapping university talent and DFW’s tech network

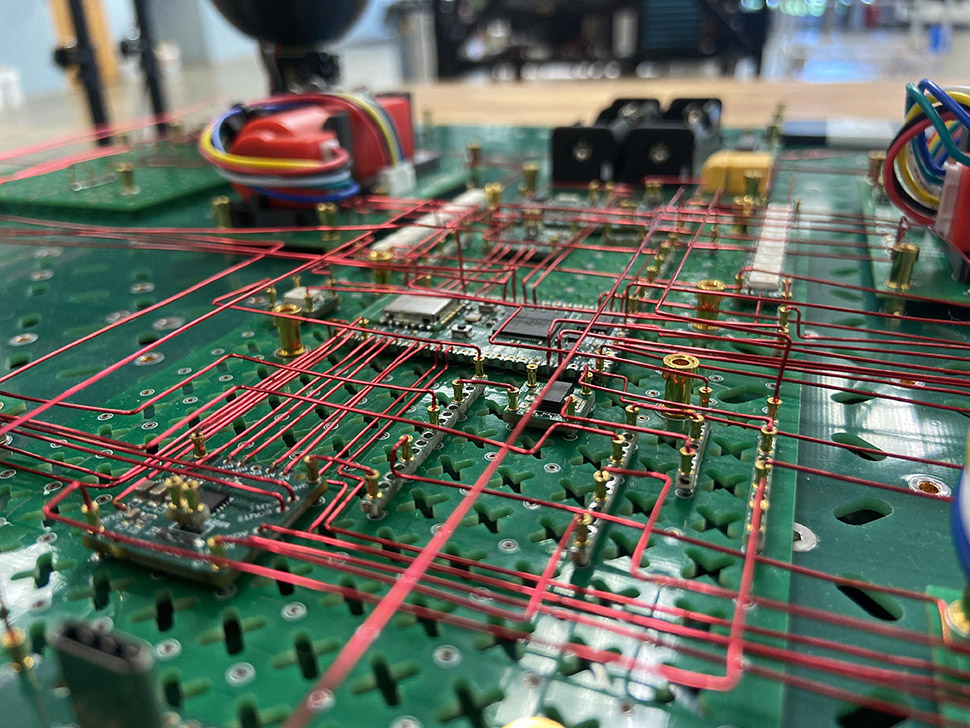

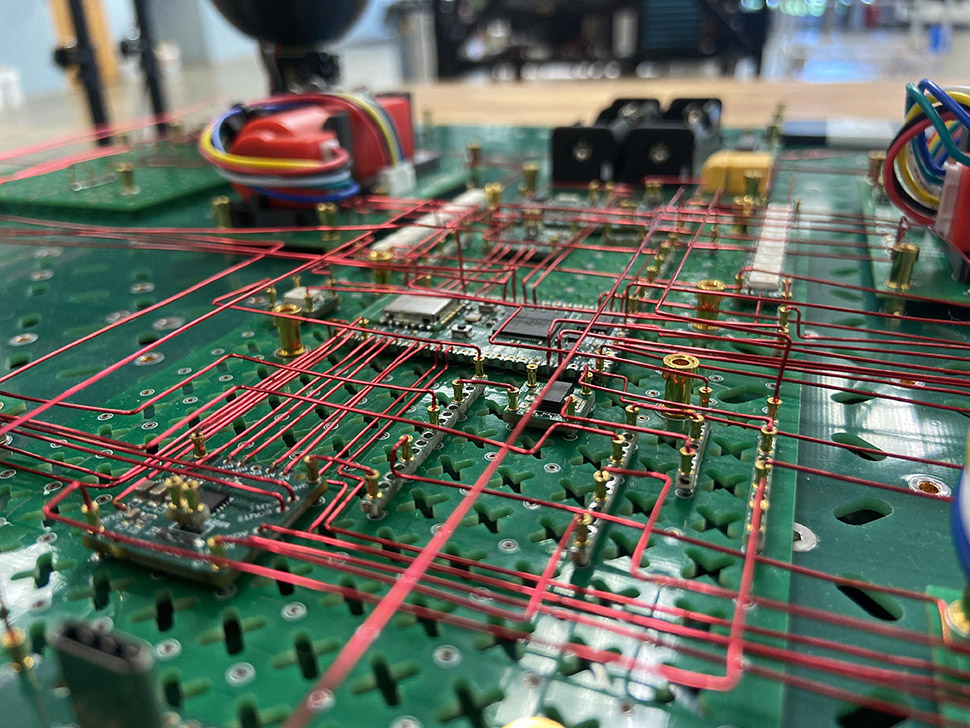

A set of molecules—Adom’s term for PCBs designed to work with its factory workcells—connected with wires by the company’s robot pincers for prototype testing. [Photo: Adom Industries]

Lauer is also tapping into the state’s growing semiconductor and tech network. He points to SMU’s tech hub and its connections through CHIPS Act and National Semiconductor Technology Center initiatives as “extraordinarily helpful” in linking Adom with industry groups and resources.

Adom has also partnered with three of Texas’ top engineering schools on early reference projects for its still-developing, cloud-native factory.

At UT Austin, students developed a robotic arm that could have AI algorithms played back through it for training. At Texas A&M, an engineering team delivered what Lauer described as “a core piece of our robotic factory”—a wire-bending solution to automate electrical connections inside Adom’s workcells.

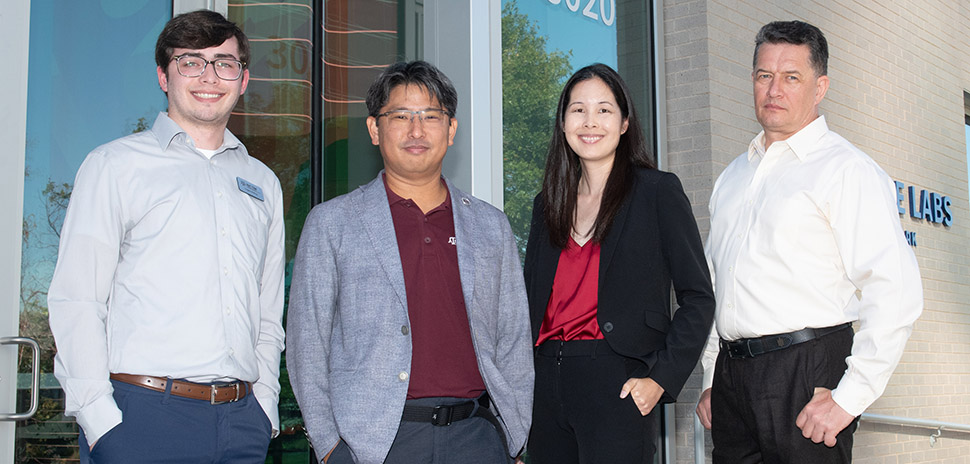

Locally, at UT Dallas, Marco Tacca, a senior lecturer in electrical engineering who collaborated with Lauer and his team on student capstone projects, says Adom is unlike anything else in the market. “As far as I know, it’s something that doesn’t exist anywhere else,” he told us.

Tacca advised a capstone team over two semesters to prototype what Lauer calls “one of our first prototype projects.” For a drone assignment, his students designed all the “molecule” building blocks needed to assemble and fly it.

Adom’s molecule approach, Tacca says, could give students and researchers access to tools most universities can’t afford or keep up to date. “Instead of buying an Arduino or Raspberry Pi, you’d choose from a library of these modules and connect them like Legos,” he said. “Then you’d do what you need to do—measurements, firmware development, testing—all remotely.”

Adom’s shared, cloud-based approach can also give students and researchers access to high-end tools that stay current without requiring universities to purchase or maintain them, Tacca adds—an expensive proposition that some schools can’t justify, and even when they can, the equipment can become outdated.

All the tools, none of the overhead

A set of Molecules—Adom’s term for PCBs designed to work with its factory workcells—connected with wires by the company’s robot pincers for prototype testing. [Photo: Adom Industries]

The kind of equipment needed for modern electronics design can easily run into the millions, Lauer said. “Who can afford that?” he said.

Adom’s platform changes that equation by turning specialized tools into an on-demand service.

“If they’re coming into our facility through their laptop, and they’re renting that equipment for one hour, they’re paying a few dollars. You’ve got 23 other people using it that day, all sharing the cost. That’s never actually been possible before, ever in the history of electronics design.”

That cost shift, from a capital expense to a shared operating expense, removes the need for every company, university, or startup to own and maintain their own high-end test lab. And it changes the hardware playbook that, for decades, has sent engineers halfway around the world to build at speed.

“Today, you’re told to go live in Shenzhen, China for the next two years while you work on your circuit boards,” he said. He’s bringing that stateside.

The Chinese manufacturing hub has dense supply chains, massive prototyping capacity, and ready access to production. “Shenzhen has a shopping mall that is eight stories tall, with every electronic component in the world available to you. We’re moving Shenzhen into the United States through a cloud factory that everybody can access.”

“Once you put it under one roof, you get the benefit of the critical mass of everybody being able to access that expensive equipment,” Lauer said.

Semiconductor-adjacent, aimed at every corner of electronics design and prototyping

In April, Adom Industries presented to U.S. Secretary of Education Linda McMahon and Dean Kamen, founder of FIRST, at the FIRST Robotics Conference—showcasing the company’s role in the future of electronics prototyping in America. [Photo: Adom Industries]

While Adom Industries isn’t building chips, per se, it could influence how fast and affordably those chips get developed, tested, and brought to market.

That positions Adom as what many in the industry would call “semiconductor-adjacent.” Not a chipmaker, as some early reports cast the company, but an enabler of innovation across the electronics industry.

And it comes at a time when manufacturers are looking to flexibility, adaptability, and investment in technology to navigate rising costs and geopolitical challenges.

“The defense department should be one of our biggest customers in the future,” he said. But, he adds, the base is broad.

“It will be the full gamut of anybody doing electrical engineering,” he said, from defense contractors and large semiconductor firms like Texas Instruments, NXP Semiconductors, and STMicroelectronics, to mid-sized companies and healthcare labs developing electronics for medical devices.

The mix could also include startups “building the next robot lawnmower that self-drives,” as well as universities running cloud-based electronics courses for students who don’t have access to a physical lab or the right equipment.

“Everyone from that whole base of customers is constantly trying to keep up with the Joneses with the latest equipment,” he said.

Advanced manufacturing and AI-powered design converge in Adom’s model. The platform links physical robotics with AI tools such as Claude, ChatGPT, Gemini, and even Elon Musk’s graph models—layered over a vast library of components—through a network of custom-built software agents tied to Adom’s knowledge base.

“Nobody’s really ever connected the AI to physical robots that are controlling a factory,” Lauer said. The result is what’s generally known as a “dark factory”—a facility where robots handle the core production, with humans on hand mainly for maintenance.

That integration could eventually allow engineers, and even the AI itself, to design and prototype new electronics with minimal human input. “In the future, you’ll ask the AI to design your electronics for you,” Lauer said. “And we will be that company.”

The Fort Worth calculus

As Adom Industries works through different incentive options, the company has temporary space in the AllianceTexas development, where early workcells and robotics systems are in progress. But Lauer says the permanent factory site isn’t guaranteed to land in Fort Worth.

“The Fort Worth tax abatement offer helps tilt the scales,” he said.

![Michael Hennig, Fort Worth’s economic development manager, presents the Adom Industries proposal to the City Council in early August. The four-phase, $229 million project—code-named “Project Nimbus”—is up for a vote on Aug. 12, 2025. [Screenshot: City of Fort Worth video]](https://www.europesays.com/us/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/Screenshot-2025-08-10-at-2.15.46-PM.jpg)

Michael Hennig, Fort Worth’s economic development manager, presents the Adom Industries proposal to the City Council in early August. The four-phase, $229 million project—code-named “Project Nimbus”—is up for a vote on Aug. 12, 2025. [Screenshot: City of Fort Worth video]

When Michael Hennig, Fort Worth’s economic development manager, presented the Adom project proposal to the council last week, it was described as a “four-phase project leading to the development (and expansion) of an electronics prototyping lab, electronics workbench, and semiconductor fab for cloud-based users.”

Hennig framed it as part of the city’s strategy to expand R&D activity. “R&D-intensive projects tend to involve jobs that pay higher salaries,” he said, adding that such investments help boost per capita GDP and drive growth in the city’s target industry clusters.

Innovation coordinator Kelly Baggett positioned the deal as a way to expand Fort Worth’s role in the semiconductor ecosystem, moving beyond its historic aerospace and defense strengths. “This area is increasingly known as a semiconductor corridor,” she said, citing recent investments from Taiwanese electronics manufacturer Wistron ($687 million), MP Materials, and Siemens.

Baggett told council the $15 million incentive package was intentionally structured to support Adom’s early-stage R&D needs, calling the Economic Development Investment Fund (EDIF) grants in the first two years “a big reason why this company is choosing Fort Worth in the first place.”

“The EDIF grants deliver value where it matters most, during the heavy R&D phase and the factory ramp-up,” Baggett said. “Early-stage semiconductor R&D prototyping is extremely capital intensive, and these early incentives enable the company to de-risk that early period.”

The performance-based structure includes phases tied to specific deliverables, and if salary or job commitments aren’t met, annual grants can be reduced or forfeited. The city projects a 21-to-1 private-to-public investment ratio, with its $15 million in incentives representing $12.4 million in lifetime value, or $7.6 million in present dollars, and expects to break even within seven years.

Adom’s proposed headquarters and factory would be built in four phases, anchoring at 4400 Alliance Gateway Freeway in the initial phase. Future phases must be located in Fort Worth. The $229 million development, targeted for completion by 2033, would include $182.5 million in equipment and $46.75 million in real estate improvements, according to city documents.

The Fort Worth City Council is scheduled to vote on the program agreement on Aug. 12, during its 6 p.m. meeting.

Don’t miss what’s next. Subscribe to Dallas Innovates.

Track Dallas-Fort Worth’s business and innovation landscape with our curated news in your inbox Tuesday-Thursday.

R E A D N E X T

-

The Tech Transfer Showcase spotlights life science innovation at universities and strengthens the development of future leaders and entrepreneurs, BioNTX said. Here are the six university finalists who’ll be pitching at the summit.

-

The new center at Bridge Labs will train the workforce powering North Texas’ biotech boom—helping startups speed therapies, vaccines, and breakthrough biologics from lab bench to patients. Funded in part by Lyda Hill Philanthropies, the National Center for Therapeutics Manufacturing Satellite Campus is set to open this summer.

-

The study of data from past storms includes researchers from multiple universities as well as international partners from hurricane-prone regions including the Bahamas, Jamaica, and Costa Rica.

-

![A NASA illustration depicts the idea of a future air taxi hovering over a municipal vertiport. [Rendering: NASA/Lillian Gipson and Kyle Jenkins]](https://www.europesays.com/us/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/DRC-NTCOG-NASA-970-970x464.jpg)

The federal research laboratory slated for Texas A&M-Fort Worth will be focused on innovative aviation technologies—including drones, air taxis, and supersonic and hypersonic aircraft.

-

Dallas Innovates, in partnership with the Dallas Regional Chamber, once again is recognizing the most innovative leaders in AI in Dallas-Fort Worth. From visionaries and mavericks to transformers and academics, AI 75’s class of 2025 are the AI pacesetters you need to know now.