Thirty-two year-old Ashley Gutierrez was taken to the Harris County Jail in the early hours of a February morning after being involved in a car accident.

Intake personnel, which includes professionals from Harris Health and the Harris Center for Mental Health and Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, refused to admit her, saying, according to Gutierrez, that she looked like she needed medical treatment.

“I was covered in blood,” said Gutierrez, who asked that her real name not be used because her charges are pending. “I had a broken nose, a gash on my throat from the airbag deploying, and I didn’t know it at the time but I had a broken neck.”

She was taken to LBJ Hospital, where she says she was denied admittance because her condition appeared to be severe. She ended up at Ben Taub Hospital and was released after two days, allegedly in good enough shape to go back to the Harris County Jail.

According to Gutierrez’s account, she was unable to walk so an officer lifted her from a wheelchair into the back of his patrol car. On the way to jail, she passed out. An ambulance was called and she was once again taken to Ben Taub, where an MRI was done and the broken neck was discovered. She says doctors told her that valuable time was wasted when she should have been lying flat and in a neck brace. She could have been permanently paralyzed, she says the medical professionals told her.

Gutierrez said she spent nine more days in the hospital and was taken again to jail, where she remained for three weeks confined to a neck brace and a wheelchair until she posted bond.

She was asked questions about her mental health and medical history while in the hospital but not during intake at the jail, she said. Once incarcerated, she was given Tylenol and a Benzydamine patch for pain. She was housed in a six-bed cell with two other women and says jail personnel would not help her shower or go to the bathroom.

Sheriff’s Office Senior Policy and Communications Advisor Jason Spencer said the screening process involves taking blood pressure and vital signs and determining the inmate’s medical history and whether they have any prescriptions.

“That happens,” he said when asked about whether inmates are sometimes refused admittance to the jail and sent instead to a hospital. As for how it’s determined that a person is fit to be handed over to the jail after a hospitalization, “that’s done in consultation with the medical provider,” Spencer said.

Michael Henninger, who asked that his real name not be used because he is currently incarcerated in the Harris County Jail, was arrested in April and transported to jail following a brief hospitalization during which he detoxed from crack cocaine and was treated for injuries. The intake process was simple and streamlined, he said. He answered some questions about his state of mind and previous medical history. He was not given any medication.

There doesn’t seem to be any protocol in place as to how or to whom medication is prescribed, Henninger said. The Harris County Sheriff’s Office contracts with Harris Health and The Harris Center for Mental Health and IDD to screen inmates prior to admission. Harris Health provides primary care and hospital and clinic services. The Harris Center focuses on behavioral and mental health.

The Harris County Sheriff’s Office reports that about 26 percent of its population of 8,716 inmates are on psychotropic medication.

“Lots of mental illness in here and lots of drug use and misuse of medications,” Henninger wrote from jail last month. “It seems the people that use drugs are the ones collecting the most pills each day and many of them sell them and trade for them. And I have seen several people who appear to have serious mental health issues that are not on any medications. Lots of physical violence, crazy fights in here!”

Violence and mental health struggles are to be expected at the largest jail in Texas. It’s understaffed and has been found out of compliance by the regulating authority Texas Commission on Jail Standards numerous times since 2022, primarily because of a low officer-to-inmate ratio.

“Like any jail, we have incidents where inmates assault each other,” Spencer said. “The overwhelming majority of the people who are in our jail are charged with a violent crime and they’re in tight quarters. Fights happen.”

Gonzalez reported to the Texas Jail Commission last week that there are 121 detention officer vacancies with 40 new hires starting this week and a class of new recruits that starts training on August 18. “We’re on the verge of being fully staffed,” Spencer said. Starting pay for a newly hired detention officer is about $46,550 a year before overtime, he added, and recruiting events are held frequently.

In 2024, the jail reported 10 in-custody deaths. So far this year, there have been 12. One of the most recent Harris County Jail deaths, that of 32-year-old Alexis Jovany Cardenas, has sparked a public discussion about whether detention staff are equipped to identify a person experiencing a mental health crisis and whether Cardenas would be alive today if he were taken to a hospital instead of the county lockup.

Cardenas’ family says that when he approached a Houston police officer in a parking lot on July 6 and asked for help, he was suffering a mental health breakdown. Because he had an outstanding warrant for a traffic ticket that was several years old, the officer took him to jail, where he stayed for about 30 hours.

Alexis Cardenas, pictured with his four children, died July 8 in the Harris County Jail.

Photo by Melissa Cardenas

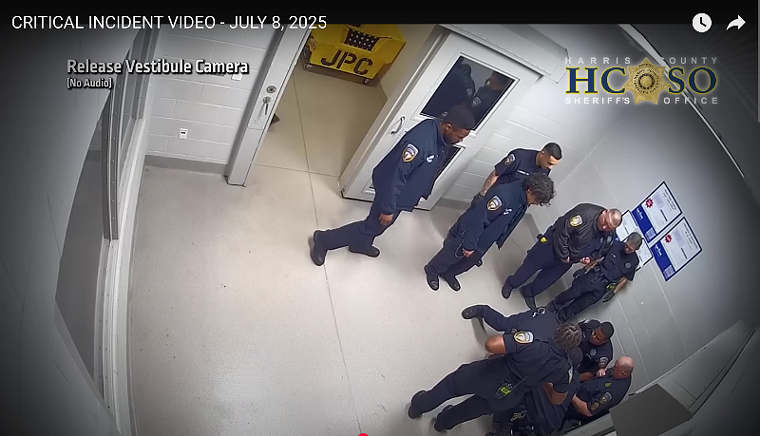

As he was being released around midnight on July 8, he resisted, apparently still fearing for his life, and after a struggle with detention officers in which a Taser was deployed, Cardenas died. The scenario was captured in a 17-minute video released earlier this month by the sheriff’s office.

The cause of death is pending autopsy and numerous investigations are underway to determine what happened during Cardenas’ final moments. A report filed by emergency medical technicians following the incident shows that Cardenas experienced cardiac arrest and was assaulted. No alcohol or drugs were in his system, according to reports.

“Of course, we are concerned any time that a person in our custody passes away and we strive to do everything in our power to ensure that people leave our jail at least as healthy as they were the day we received them,” Spencer said in an email. “This is why Harris County spends nearly $100 million annually on a jail healthcare operation run by Harris Health that is designed to far exceed the minimal levels of jail healthcare mandated by state standards. It’s why we invest significantly in training for our detention officers that also surpasses minimum standards.”

Sheriff Ed Gonzalez said at a press conference following Cardenas’ death that one sergeant and six detention officers were temporarily reassigned to “duties that do not entail contact with inmates until we have a more complete picture of what happened.”

Krish Gundu, cofounder and executive director of the Texas Jail Project, said the video of Cardenas’ death clearly depicts a man in crisis who was afraid for his life and concerned about being released late at night without a working cell phone. It also appears that several officers used force to subdue a man who needed mental health assistance, Gundu said.

“You all keep talking about being understaffed but you had plenty of people to kill one man,” she said. “There are two hands on his neck and back for such a prolonged time. There was no effort [by the officers] to de-escalate. It was all escalation.”

Alexis Cardenas’ death at the Harris County Jail was captured on a 17-minute video released August 1 by the sheriff’s office.

Screenshot

Gonzalez said at a recent press conference that when Cardenas was booked into the jail, he underwent a standard medical screening. “This 38-question process revealed no major physical or mental health issues,” Gonzalez said.

Based on conversations with current and former Harris County inmates, the intake process appears to vary. Some have said the mental health screening is done on a kiosk, and if the detainee is intoxicated or unable to answer questions, an officer does it for them.

“You do the best you can,” Spencer said in response to a question about how an intoxicated person can fill out a questionnaire. “There’s an opportunity on the forms for the arresting officer to give their observations of the person.”

Harris County houses up to 9,000 inmates at any given time. Almost 80 percent of the inmates currently in custody have “mental health indicators,” signifying a history of mental health problems or experiences of serious psychological distress in the 30 days prior to intake.

A mental health indicator does not necessarily equate to a psychotic break; it could mean that the person suffers from alcoholism or drug addiction, said a Dallas-based licensed chemical dependency counselor who does not work directly with the Harris County Jail. Officials with The Harris Center for Mental Health and IDD agreed to answer questions by email about the intake process but had not responded by deadline.

Advocates with the Texas Jail Project say they don’t know where the data on mental health indicators comes from or how mental illness is being treated in the county jail. The Texas Commission on Jail Standards requires mental health data to be submitted through the Continuity of Care Query, Gundu said.

“The data we got from Harris Center and the sheriff’s office was complete garbage; it didn’t match at all,” Gundu said. “If the jail is saying 79 percent [of the inmates have mental health indicators], we don’t know where that’s coming from. Maybe it’s coming from 16.22 mental health screenings, maybe it’s coming from the number of people they’re issuing medications to, maybe it’s the number of magistrate evaluations that have to be ordered but it’s not clear where it’s coming from.”

Spencer said the Sheriff’s Office does not maintain the dashboard data on its website and wasn’t sure how it was compiled, suggesting that the Harris Center may have more information. “Our agency does not run that dashboard,” he said.

Health Screenings at the Harris County Jail

“Safe, secure, and efficient intake” operations are supposed to occur at Harris County’s Joint Processing Center, across San Jacinto Street from the headquarters jail.

The processing center includes a medical clinic, mental health screening, and a 24/7 diversion desk to provide alternatives to incarceration for those suffering from a behavioral health crisis, according to the sheriff’s office.

Intake occurs at Harris County’s Joint Processing Center.

Photo by April Towery

Individuals are screened at intake for medical and mental health needs and are referred to appropriate services accordingly,” said Nicole Benningfield, a senior manager with Harris Health, in an email. “Persons in custody may self-report health information and/or providers may have access to their medical history in the Electronic Medical Record.”

“Medical assessments of persons in custody are conducted in accordance with the standards set by the National Commission on Correctional Health Care and the Texas Commission on Jail Standards,” she added. “Individuals with a history of mental illness, whether by documented medical history in the chart, self-reporting, or via medical and/or custodial observation, are referred to the Harris Center for Mental Health and IDD for treatment.”

The sheriff’s department’s Justice Management Bureau is tasked with accepting and advancing incarcerated people from intake to the completion of charges by the Harris County District Attorney’s Office and pre-trial services.

“The Bureau ensures people in our custody advance through the multi-step process in a timely manner through regular status checks,” according to the sheriff’s office website. The average length of stay at the Harris County Jail is about 170 days, more than triple the state average, Spencer said.

“This is because of the backlog of cases pending trial in Harris County criminal courts,” he said.

Gundu said illness is often missed or misdiagnosed during medical and mental health screenings.

“They’re two different systems. They do two different things,” she said of the functions of Harris Center and Harris Health. “They’re both supposed to be doing different kinds of screenings at intake. This is typical in most jails that this is where people fall through the cracks and everybody can say confidently, we did our jobs.”

Harris County Jail Deaths

Three in-custody deaths were reported at the Harris County Jail in January.

The “manner of death” for Denaly Matute, 70, is listed as “illness/natural.” Erik Carlson, 23, died in a Louisiana hospital after being taken there for an unknown medical condition. He was one of thousands of Harris County inmates who are outsourced annually to out-of-state facilities. Sheriff Gonzalez said last week at a Texas Jail Commission meeting that ending outsourcing is a top priority.

Kristopher McGregor, 39, also died of an apparent illness. Autopsies are pending and investigations are underway.

Two in-custody deaths were reported in February: Eric Jackson, 23, and Devin Williams, 55. Jackson “suffered an apparent medical emergency in his cellblock and was taken to the clinic,” according to sheriff’s office documents. “While the circumstances surrounding Jackson’s death will be the subject of multiple standard investigations, preliminary information indicates that he had no apparent significant injuries.”

Williams was being booked on a drunk driving charge and was sitting in the Joint Processing Center when jail staff noticed he was unresponsive, and medical personnel determined he was deceased, according to sheriff’s office records.

Jose Cisneros, 52, died in May after spending almost two years in jail awaiting trial on a murder charge. Jail records show he was transported to LBJ Hospital with a pre-existing medical condition and died May 27.

Four in-custody deaths were reported in June and three of those occurred within a 48-hour period.

The first June death, that of 26-year-old Valen Long, is pending autopsy.

“Preliminary evidence indicates that Long was among multiple inmates who were smoking an unknown substance around 12:30 a.m.,” according to sheriff’s office documents. “Inmates alerted detention officers when Long suffered an apparent medical emergency and lost consciousness shortly after smoking the unknown substance. He was taken to LBJ Hospital by ambulance, where he was declared deceased.”

Spencer said that, like most jails and prisons across the nation, Harris County has seen an uptick of inmate deaths caused by overdoses, usually from substances smuggled into the facility.

“Also, like most jails, our population includes high rates of mental illness, alcoholism, drug addiction, and chronic illness, all of which contribute to a facility’s mortality rate,” he said. “People smuggling drugs into jails is not a new thing. What has changed in these last few years is that frequently what’s getting smuggled in is deadly.”

“In the past, they would soak paper in a substance and would mail it in to an inmate and the inmate would smoke it,” he added. “That’s why we’ve eliminated paper mail in the jail. We’ve had cases where attorneys have been charged with crimes for smuggling or passing drugs to their clients at the courthouse or during visitation.”

The manner of death for Ronald Erwin Pate, 35; Alexander Winstel, 43; and Phillip Brummett, 68, is unknown pending autopsy but all three “suffered medical emergencies in jail” prior to death. The men died within a two-day period on June 22 and June 23. Winstel and Brummett had been in custody for less than a week.

“The fact that two of them died within four days of being booked tells me that they were probably unfit for confinement when they came in,” Gundu said. “They probably should have been sent to the hospital.”

Harold Alexander Jr., 62, died July 10. Officers found him unresponsive on a mattress. An autopsy is pending.

Cardenas’ death on July 8 has been the subject of much scrutiny but isn’t listed as an in-custody death on the sheriff’s office website, presumably because there’s a question of whether he was actually in custody at the time of his death. He was in the process of being released but appeared to want to stay in jail because, according to his family, he feared harm awaited him outside.

The incident with Cardenas is, however, reported on the statewide custodial deaths database maintained by the Texas Attorney General’s Office. A brief summary states that Cardenas exhibited medical problems but mental health problems were “unknown.”

“On July 6, 2025, the decedent was arrested on Class C Municipal Warrants by the Houston Police Department, transported to the Joint Processing Center, and booked into the Harris County Jail,” the summary states. “On July 8, 2025, two officers escorted the decedent to an exit door and opened it, after he was released from custody. The decedent refused to exit the building, and a struggle ensued, including the discharge of a Taser on the decedent.

“The struggle continued, restraints were applied, and the decedent became unresponsive. CPR was started, and medical staff arrived, continuing life-saving measures. Houston Fire Department personnel arrived, assumed care, and transported the decedent to an outside hospital. At 1:57 a.m., a medical doctor pronounced death.”

Benningfield, the Harris Health manager, said she could not address specific cases and would not speculate on causes of death. “All deaths in the Harris County Jail are reviewed and autopsy reports are pending in these cases to determine the cause of death,” she said.

Gundu claims that three of the five men who died most recently in Harris County custody had a long history of cycling through state psychiatric hospitals and correctional facilities.

“Public health issues become public safety issues when they’re not connecting people to the appropriate level of care when they need it,” she said. “They keep cycling in and this is what happens. This is the outcome.”

Gundu said that when reviewing Cardenas’ death, it’s important to remember the context of how he was brought into the jail and how he exited.

He flagged down an officer and asked for help because he thought someone was going to harm him, she said. He should have been taken to a hospital, and if that had happened, he would surely be alive today, his family believes. The video of his release shows him pointing to a phone, although no audio is available.

Gundu said it appears he was concerned that, because he was being released at midnight, he wasn’t going to be able to reach anyone to pick him up. He would essentially be loose on the streets of downtown Houston without a working cell phone and no way to contact his wife or other family members.

“How was he going to get home? Who was he going to call?” Gundu said. “Why would you want to release somebody that you arrested in a mental health crisis, did not connect with mental health services, and who was continuing in crisis, at midnight with a phone that was dead and broken?”

Texas law requires that inmates be released between 6 a.m. and 5 p.m. on the date their sentence is discharged unless they consent or special circumstances apply, such as being transferred to prison or a state mental health facility.

“We don’t want to hold anyone in jail longer than they are required to be in jail,” Spencer said. “Once a judge has ordered the release of a person or a person has met all the conditions required to be released, then we feel an obligation to let that person out of jail as soon as possible.”

“If a person doesn’t want to leave because of the time of day, then we give them the option of staying until the next morning. I’m not going to get into it about a specific case.”

Once an inmate is no longer in Harris County’s custody, it’s not the jail’s responsibility to find them a ride home. “They’re adults,” Spencer said. “The overwhelming majority of people who are in jail want to leave as soon as they can possibly get out.”

Gutierrez said she was released at about 2 a.m. on a Saturday and had a family member pick her up. When she and another female inmate went to retrieve their belongings, she claims she was told that the jail was out of “emergency clothes.” The outfit she’d been wearing at the time of her accident was covered in blood and had been cut off at the hospital so her original clothes weren’t available, she said.

“They went through other people’s stuff and gave me someone else’s clothes,” she said.

Spencer said the jail provides “disposable clothing” to inmates who are being released when the clothes they arrived in aren’t available.

“It’s almost like a jumpsuit-type outfit that we give them,” he said. “No, we don’t give them another inmate’s clothes. We have clothing. It’s temporary. It’s just enough to cover you up. It’s flimsy. It’s not something you would take home and put in the washer and use again.”

The jail experience isn’t supposed to be a day at the beach, Gutierrez conceded, but it’s not unreasonable to expect one’s mental and physical safety to be prioritized.

“I’m lucky to be alive,” she said.