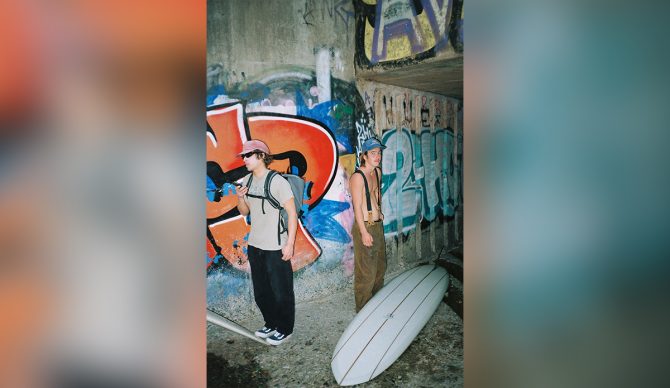

This shot of Stroud’s shaper friend roaming L.A.’s arts district ultimately became the cover of his book, Candid Observations in Transcendentalism. Photo: J.D. Stroud

![]()

It’d been pissing rain the whole week. Howling November winds whipped through the air, as 10-foot waves swelled under the dark grey skies of Saint-Jean-de-Luz. While most people had vacated the stormy French coastline, indie photographer and filmmaker J.D. Stroud was tucked into the breakwall rocks.

“You couldn’t even look to see him,” surfer and Lighthouse Skate Shop co-owner Spencer Navarro recalled. “He had his umbrella up, and the tide would just shift so much, he was just sitting in the rocks.” Navarro, Stroud, and a shaper friend were on a 10-day surf trip in the French Basque Country. Navarro, 33, was in the thick of it, surfing through the storm on a custom longboard.

By the time he and the shaper got out of the water, Stroud was walking to their rental car, with an inside-out umbrella in one hand and a camera in the other. “We get to the car… and he’s shaking, and he, like, can’t talk” Navarro recalled. “His umbrella is just completely upside down, like he’s about to fly away.” When asked what happened, Stroud shivered, completely soaked, and told Navarro: “I wanted to film you guys.”

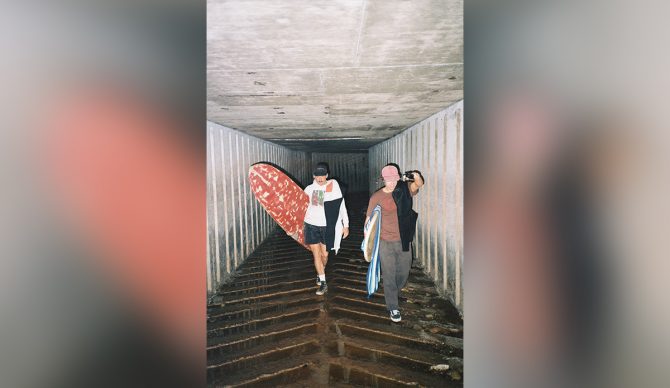

Traversing the beach in Saint-Jean-de-Luz. Photo: J.D. Stroud

The moment exemplified everything Navarro’s come to admire about Stroud and his work since the pair met at Malibu First Point some years ago. Navarro described Stroud as an old-school skate filmer turned surf photographer, and credits him for his unique eye. “J.D. would always be tucked into these corners, and so far away,” Navarro said, “I just always really liked his approach and his style… and how it made the wave look.”

Photo: J.D. Stroud

When I met up with Stroud in Venice Beach, he was calm and unassuming. We discussed everything from his earliest surf memories, to his personal photography journey, and his inevitable immersion into eccentric, non-professional surf scenes around the world.

He described how, that same stormy week of his 2022 trip with Navarro, he captured a moment that he called one of his most cherished surf memories. “Spencer paddled out on a 10-foot longboard, on a single fin,” Stroud said, stressing how ill-advised longboarding is in that kind of weather, “and God, he pulled into one wave switch-stance, and got one of the most beautiful barrels on a longboard I’ve ever seen.” The clip’s since been immortalized in Stroud’s 2022 surf film, Magenta.

As Stroud detailed the events of that trip, his passion and gratitude for all the people he’s met through surfing became increasingly evident. He was adamant about crediting French photographer and filmmaker Vincent Lauzel (who he met abroad) for serving as his unofficial Basque Country surf guide. Stroud cares deeply for people, and with work featured in Leica’s LFI magazine, a handful of surf films, and a self-published book under his belt, the California-born photographer is quietly cementing his place in the alternative surf scene.

Stroud, 34, was shaped by California. He spent his youth roaming Orange County beaches unsupervised, where strangers would hand him boards and urge him to paddle out. At 19, he lived in a cave for a summer, working odd jobs between sessions at Sunset Cliffs. His life quickly anchored around the worlds of surfing and skateboarding. “From a young age, I had a serious obsession with documenting things,” he explained. Art Brewer and Taylor Steele were his earliest influences.

Stroud’s oeuvre is full of wide landscapes. Photo: J.D. Stroud

Now based in Topanga, Stroud described his subject matter as “alternative subsects, cliques, and niches within the surfing diaspora of Los Angeles county.” It’s a wide-ranging group, he explained, encompassing people of all walks of life. “There’s so many people who congregate together to surf a specific location, who come from so many different backgrounds,” Stroud explained, “It’s a melting pot of strange characters who all come together to do one thing.”

Photo: J.D. Stroud

Stroud’s work amplifies the spirit of the alternative surf scene, taking a warts-and-all approach to capture the ethos and lifestyle of diehards who live to surf. Some might assume that includes WSL athletes, or surfers seeking sponsorships. But Stroud stressed that’s not the world he’s drawn to. “When I look at professional surfing, I think, okay, those guys are the absolute best of the best, [they] worked extremely hard to get what they have and to do what they do, and it’s inspiring,” Stroud explained. But as subject matter for his art, Stroud admitted pro surfing doesn’t hold much appeal. “I think I would find it a little boring,” he explained. “There’s a lot of beaches in California now where you do show up… and there’s 15 to 20 guys with telephoto lenses, sitting in the exact same spot, taking the same photo of the same surfer. And, to me, it seems jaded.”

The grainy textures and blurred motion found throughout Stroud’s work oppose the crisp, clean aesthetic of commercial surf photography. Photo: J.D. Stroud

Professional or not, Stroud asserted surfing’s core ideals are universal. “You go out there, you prove yourself… you progress, you respect the people that came before you, and you experiment,” he said. But in the water, the pro and non-pro world deviate in terms of style and equipment, and Stroud finds the non-pro world more colorful. “A lot of the more creative, alternative surf world rides things that a professional surfer on the circuit would never ride,” he explained, “if you go to Malibu, you’ll see guys on mid-lengths, with single fins, twin fins, and weird, funky boards they made themselves.” It also comes down to the way these surfers ride. Stroud’s drawn to their style, and enthusiastically described “the way they lay into turns” on a longboard, or how they “stay in the pocket on the nose.” Beyond that, Stroud claimed what most telephoto photographers fail to grasp is that the culture outside of the water holds equal weight in defining surfing’s identity.

Stroud is drawn to the unique style exhibited by alternative surfers. Photo: J.D. Stroud

Stroud cherishes the rich tapestry of surf culture, and has become somewhat of a torchbearer for the alternative scene’s raw soul. Stroud’s world consists of surf-obsessed individuals who often have no interest in capitalizing on their passion. Most know the type: local mainstays living in vans perpetually parked by the shoreline. But when he described these surfers, Stroud was quick to point out that just because these people have built their lives around surfing, they’re not necessarily all surf bums.

Parking lot hecklers coexist among painters, creative executives, construction workers, and drifters who live lifestyles that allow them to stay at the beach for days. Anybody whose job or home life comes second to surfing fits the mold. What Stroud finds beautiful about surf culture is how it blurs socioeconomic lines. He put it like this: “No classism exists in that community. There’s no polarization that exists in that community. And to me, from an outside perspective, the thing that becomes unfathomable is that that doesn’t exist in a whole lot of other communities.” Stroud’s work captures the chaotic menagerie of the surf culture melting pot, and documents a raw, un-sanitized portrayal of surfing not as sport, but as a lifestyle, practice, and artform.

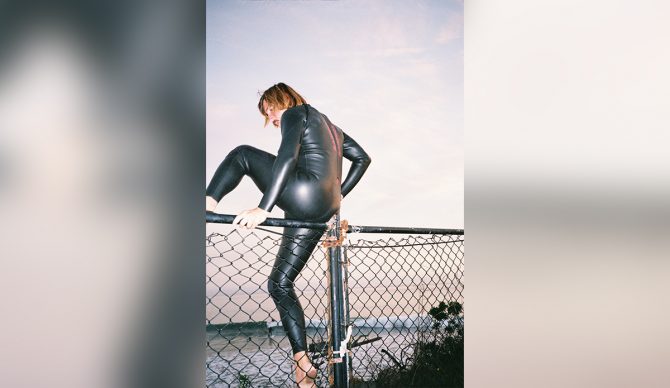

Testing the fences. Photo: J.D. Stroud

When it comes to still photography, Stroud does his best to serve as a documentarian. He described his style as “candid and unabated.” He doesn’t do much in the way of post-processing and he picks his moments carefully. “I kind of only choose to use a camera when people are unaware of me using it,” he explained. “I have never really had to edit a photo. I don’t know if that’s bragging, or if that’s naive. It’s just honest photography,” he said.

But because California is painted as a surf Mecca by pop culture, alt surfers are often exploited for their aesthetic, and that exploitation pains Stroud. “I’ve seen a lot of photographers try and handpick surfers and do staged things,” he explained, “[The photo] ends up on a billboard for some huge brand, and that guy never saw a dime.” Stroud clarified that this mostly happens with non-surf brands, but it still creates tension. Sponsored surfers are taken care of, they’re outfitted, or paid to compete. There’s a clear understanding of the exchange: wear the logo, get paid. But when non-pros are used to sell products and aren’t compensated, it speaks to a larger imbalance in surf culture, where authenticity is mined from the fringes.

Trace Marshall surfing the south side of the Malibu Pier, winter 2018. Photo: J.D. Stroud

His understanding of that tension is perhaps why Stroud takes his role as a photographer so seriously. Though he credits people like photo essayist Trace Marshall for creating meaningful work that accurately and ethically portrays the L.A. surf scene, Stroud asserts that it’s difficult to find others who respect the alt scene and attribute that same level of value to their surroundings. “It’s hard to find people who are actually viewing whatever beach they hang out at the most, or whatever scene they’re in, as something worthy of documenting,” he explained.

Photo: J.D. Stroud

That search for like-minded surfers and artists is what brought Stroud to Europe in 2022. “Europe, I don’t think it strikes people as the first place they want to go on a surf trip,” which he explained, “makes a lot of the surf culture there really core and interesting.” French visitors Stroud met at Malibu First Point ultimately pointed him to the Basque region. He’s grateful to have discovered a parallel surf culture that’s populated by photographers like Vincent Lauzel, who place equal weight on surfing as an art form.

Suffice to say: Stroud, and artists like him, are on a perpetual search for authenticity. They use their art to protect and elevate their lived experience as surfers. For Stroud, photography is preservation. Most recently, Stroud was featured in the fifth volume of Estevan Oriol’s Contagious Culture book series. His career is one to watch, and his point of view is essential.

J.D. Stroud’s Book, Candid Observations in Transcendentalism, can be found here.