Theodore C. Van Alst Jr. has always been a good storyteller, the kind whose friends and family say things like, “You need to write this stuff down,” but it took him many years to follow their advice. Born in Chicago’s Uptown neighborhood, Van Alst attended Sullivan High School in Rogers Park, earned his GED while serving in the U.S. Navy, continued on to higher education in his mid-30s, and now works as professor of Indigenous nations studies at Portland State University. A lifelong avid reader, he finally began writing down his own stories after editing The Faster Redder Road, a collection by popular horror writer Stephen Graham Jones, ten years ago.

Now, at age 60, “I can’t really turn it off,” Van Alst says of his writing, and that’s welcome news for readers who enjoy books set in Chicago. An enrolled member of the Mackinac Bands of Chippewa and Ottawa Indians, Van Alst wrote a trilogy of mosaic novels about growing up in Chicago (Sacred Smokes, Sacred City, and Sacred Folks); he also contributed to the recently published Red Line: Chicago Horror Stories and coedited the national bestseller Never Whistle at Night: An Indigenous Dark Fiction Anthology.

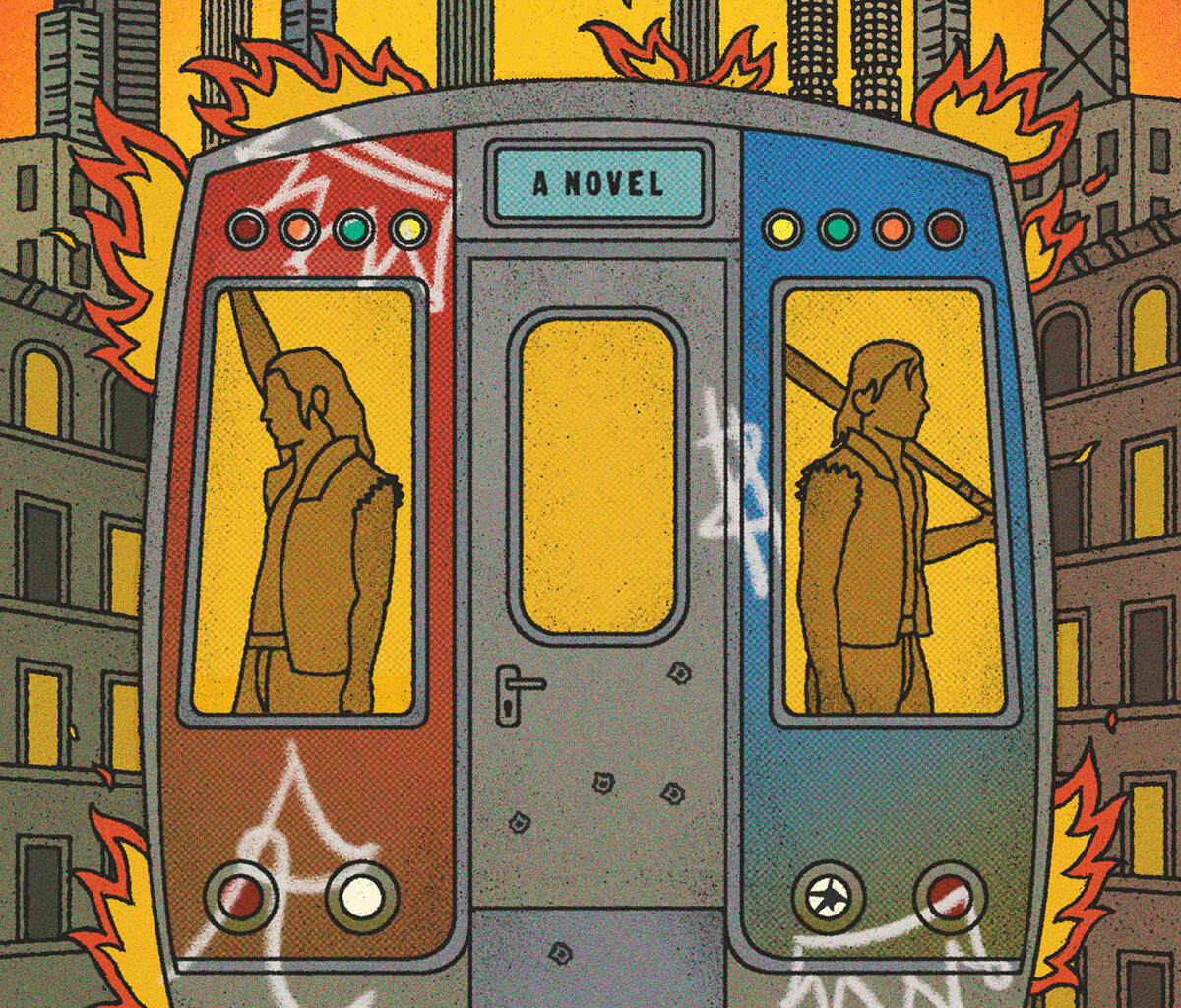

The El by Theodore C. Van Alst Jr.

Vintage, paperback, 192 pp., $17, penguinrandomhouse.com/books/738830/the-el-by-theodore-c-van-alst-jr

New Chicago Fiction: Grit and Grace panel

Sat 9/6, noon, Printers Row Lit Fest, Center Stage, S. Dearborn St. in Printers Row Parkbetween Polk and Harrison, printersrowlitfest.org, free

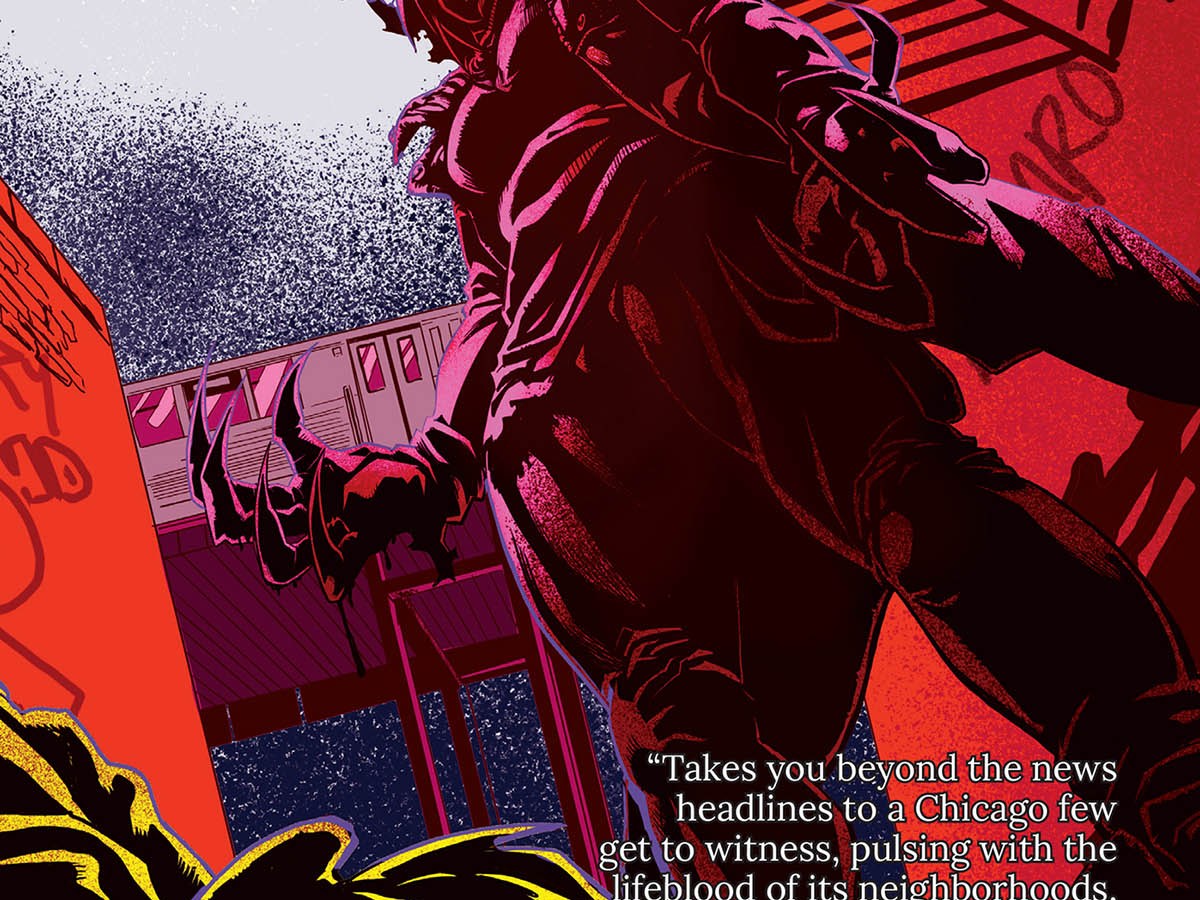

His latest work, The El, began as a semi-autobiographical short story but grew into a full-length novel as memories of his hometown and old friends poured onto its pages. Set over the course of one scorching day in August 1979, the book follows Teddy, an Indigenous teen and member of the Simon City Royals, as he leads a group of his fellow gang members on a dangerous journey through hostile territory, traveling on what are now the Red and Brown lines from Rogers Park to Roosevelt High School.

Author Theodore C. Van Alst Jr.

Author Theodore C. Van Alst Jr.

Credit: Amie Van Alst

“I’m missing Chicago every day, and I miss taking the el,” Van Alst said in an interview with the Reader. He grew up riding the train to school, downtown to watch kung fu movies on the weekends, and wherever else he needed to go. “I just wanted to write a story about taking the el and what it felt like, what it smelled like, what it sounded and looked like.” The novel is full of such sensory details, from the screech of rusty wheels to the crackle of the intercom. It also includes a map of Chicago’s train system as it looked at the time, with the addition of hand-drawn gang symbols marking the territories of Teddy’s peers and rivals.

One of Van Alst’s aims as a writer is to tell authentic stories about working-class people who care about literature, music, and art as much as anyone else. These qualities are readily apparent in The El’s Teddy, who carries a copy of Mike Royko’s Boss in his pocket, never turns off the radio in the middle of a song (out of respect, of course), and mentions in a Lincoln Park–set scene that he would love to visit the DePaul Art Museum someday, but “I didn’t think I could get in.”

“Our stories just don’t get told, and they live in a whole world that a lot of people just don’t notice,” Van Alst said. “There’s a whole group of folks in this city who are not filler, who are not just background, who are not just the people who fix your lighting or take your orders or do whatever. It’s really important to understand that our lives are equally as important to making Chicago what it is.”

In addition to his focus on working-class characters, Van Alst is passionate about telling stories of Native Chicago, especially from the north-side neighborhoods that have changed so much since his youth. “We have to tell our stories, because if we don’t, we disappear. Chicago was a huge relocation city; there was a massive Native neighborhood in Uptown. That’s gone,” he said, also noting that the American Indian Center, the oldest of its kind in the country, has since moved from Uptown to the northwest side. “If you’re not telling the stories of what it was like, then you’ll never know what you lost. And I think, to not just document loss, but to celebrate what was, is really important. . . . It’s a big responsibility to get it right.”

As Teddy puts it in the final pages of The El: “Elders always said we’re only our stories, it’s important to keep them alive.” Elaborating on what it takes to be a keeper of stories, Teddy continues, “Timing and timeliness, rhythm, volume, inflection, delivery. Those skills took years to learn, let alone master. Was there a harder job? Probably not. Was there a better one? No. Definitely not.”

Reader Recommends: ARTS & CULTURE

What’s now and what’s next in visual arts, architecture, literature, and more.

Red Line: Chicago Horror Stories creates a thrilling mosaic of the city, in all its complex, terrifying beauty.

August 7, 2025August 7, 2025

At Corbett vs. Dempsey, Rosa Barba disavows analog nostalgia.

July 30, 2025July 30, 2025

Brian Leber and Joanne Aono have found a saner, more sustainable way of living on Bray Grove Farm.

July 30, 2025July 31, 2025

A new Griffin MSI exhibit spotlights steelworkers in the Calumet region.

July 16, 2025July 29, 2025

“Far Down the Phantom Air” joins the prehistoric and the postindustrial.

July 15, 2025July 15, 2025

An after-dark exhibition at Bodock requires flashlights to see—or find—the art.

July 14, 2025August 3, 2025