Catherine Nicoll

BBC News, Isle of Man

MNH

MNH

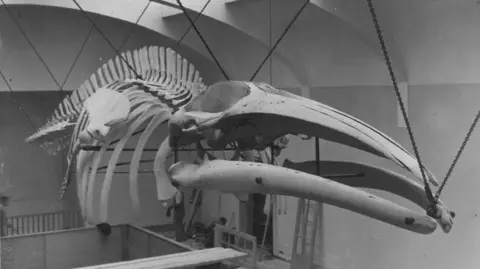

The skeleton of the sei whale has been on display to the public for several decades

A century ago, the appearance of a stranded sei whale on the shore at Langness caused shock and fascination among people on the Isle of Man.

Mammoth efforts were needed to move the 48ft (14.6m) carcass in a mission that involved ropes, chains, trailers, steam traction engines and even a tugboat.

Its skeleton remains the largest single artefact held in the Manx Museum’s National Collections, and events were held this week to mark the milestone since its acquisition.

But the whale’s arrival on Manx shores marked only the start of a final journey that would last a decade, and capture the imagination of children and adults alike.

When did the whale appear?

The female Sei Whale became stranded in a gully at Langness on the southern coast of the island in the summer of 1925.

Such was the spectacle that crowds of people, including families with children, streamed down to the shore to see the creature and even pose with it.

As the largest mammal ever to be stranded on the Manx coast, it also drew the attention of the custodians of the island’s history at the time.

MNH

MNH

The marine mammal drew crowds from across the island

As curator of natural history for Manx National Heritage Laura McCoy explained, it was at a time when natural history and antiquarian societies were very prominent.

“Things like whale skeletons were seen as a very a prestigious thing to have,” she said.

“And so when this opportunity came about, the museum was like ‘we want that skeleton’.”

But taking it into the collections of the newly opened Manx Museum was not as simple as just staking a claim on it, as all cetaceans are the property of the British Crown.

Once permission was secured for the whale to be taken locally, something had to be done to move the rotting carcass, which was by now becoming a public nuisance.

How was the whale retrieved?

Without the powerful portable machinery of the modern age, a series of manoeuvres was needed to move the whale.

That involved wrapping it in chains to drag it back out to sea where it was refloated and pulled around the coast to Derbyhaven by a tugboat.

Once there, it was hauled ashore onto large trailers using ropes and chains to allow it to be transported to an abattoir in Douglas to be defleshed.

Such was the putrid smell of decay that it is said police at the head of the cavalcade warned people along the route to shut their windows as it passed by.

MNH

MNH

Steam traction engines were used to transport the dead whale to Douglas

After the bulk of the flesh was removed from the carcass at the abattoir, the bones were buried for four years to finish the defleshing.

Ms McCoy said that allowed the skeleton to be cleaned “organically”, which was a technique still used when dealing with the marine mammals.

“A common way to prepare whale skeletons, even to this day, is to bury them,” she said.

“That allows all the little creatures and things to get into the bones and deflesh them.”

“Then you dig out your nice skeleton that is hopefully very dry and clean and not smelly.”

Why did it take another decade before it was put on display?

With that process taking about four years, the task remained of finding somewhere appropriate in the Manx Museum to house the huge specimen.

Following a fundraising effort, the Langness whale found a home in the newly created Edward Forbes Gallery, named in honour a notable Manx botanist.

The company chosen to mount the skeleton was the same London-based firm responsible for the original hanging of Hope the blue whale in the Natural History Museum in London.

Ms McCoy said while the skeletonised whale would have been “a little” lighter once the flesh had been removed, it would still have been “incredibly heavy” with the skull alone weighing more than a tonne.

The enormity of the task of mounting the creature meant it was a “fairly prolonged project”, which the records had shown had involved “barrels of papier-mache” and steel rebar, she said.

MNH

MNH

Trailers were seconded from across the island to held move the carcass

Once in situ the skeleton remained in position for the next seven decades.

That was until a revamp of part of the museum saw the opening of a new Natural History Gallery in 2005, leading to another epic task of moving the bones, this time with the help of modern techniques.

MNH

MNH

There skeleton is the larges item in the Manx National Collections

What is a sei whale?

Taken from the Norwegian word for pollock, “seje”, sei whales (scientific name balaenoptera borealis) are the third largest whale species after blue whales and fin whales.

Dark in colour with a white underbelly, they have long, sleek bodies that can grown up to 64ft (19.5m) long, allowing them to travel at speeds of up to 34mph (54km/h).

Usually found alone or in small groups, they are baleen whales which consume about 2,000lb (907kg) of plankton each day, diving for up to 20 minutes at a time to feed.

Their distribution around the world is wide with the species found in subtropical, temperate, and subpolar waters.

Listed as endangered, the marine mammals are usually seen in deeper waters, away from the coast, and have been noted for their unpredictable seasonal movements.

MNH

MNH

The Langness whale has ben prominently displayed in the current Natural History Gallery since 2005

Why is it still an important feature of the museum today?

The largest object in the museum, and Langness whale has fascinated generations of children on the island.

And Ms McCoy explained, as well as celebrating the history of the artefact, it allows for a broader conservation about the natural world and its conservation.

“What museums do best is use an object that illustrates multiple lines of inquiry,” she said.

“You’ve got the history, you’ve got the science, you’ve even got art.

“The whale skeleton is like an entryway into a bigger story if you want to go down that route.

“That’s why we love these kinds of objects and specimens because they allow us to talk about all sorts of different things and reach people in different ways.

“We want to bring kids into the museum, have a lovely day, see something really cool, and learn something interesting.

“And then they can talk about it and maybe it’ll inspire some of them to take it further when they get a little bit older… that’s always the dream.”

The Langness whale is on display in the Natural History Gallery of the Manx Museum.