By Mike Koshmrl

In late April, Jason Baldes sat at a table at the Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative’s headquarters processing a setback to his vision of restoring free-roaming bison to the Wind River Indian Reservation.

Baldes, the initiative’s executive director, is a member of the Eastern Shoshone Tribe, which had recently voted to reclassify buffalo as wildlife. They had been deemed livestock before. But he hit an impasse in persuading the Northern Arapaho Tribe, which shares the reservation, to do the same.

“It’s a bump in the road — it’s not anything in stone — but it’s a challenge,” Baldes said in the spring.

Nevertheless, Baldes remained sanguine that he could bring the Northern Arapaho Business Council on board: “I think that the [tribal] people overwhelmingly support it,” he said.

Jason Baldes, right, and his father Richard, left, check out newborn bison calves at the Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative’s pastureland near Morton in spring 2025. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

Jason Baldes, right, and his father Richard, left, check out newborn bison calves at the Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative’s pastureland near Morton in spring 2025. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

Winning over the Northern Arapaho’s leadership would be a necessary step to achieve the initiative’s goals: Amending the tribal game code so that the burgeoning buffalo herds along the eastern slope of the Wind River Range could be classified as wildlife — a key step in helping the herds eventually roam free and thrive.

“With two tribes making that distinction, we could get [bison] in the game code,” Baldes said. “Once they’re in the game code, then we can protect that population, we can grow it, and designate more habitat.”

The vision is for those changes to continue to occur slowly — and in collaboration with the reservation’s cattle ranching families, so as not to alienate the industry. “We are trying to create win-win solutions to change land use to something more holistic,” Baldes said.

Bison graze outside of the Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative headquarters in Morton in 2023. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

Bison graze outside of the Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative headquarters in Morton in 2023. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

Four months after the impasse, the National Geographic award-winner and son of a U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologist saw the Northern Arapaho Business Council change its mind. This week, the Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative shared a resolution, signed by the unanimously united council on July 15, that called for designating buffalo as wildlife.

The resolution states support for the Wind River Tribal Buffalo Initiative and its own tribal buffalo restoration efforts and recognizes that bison “were and remain central to the culture, health and welfare of the Northern Arapaho Tribe since time immemorial.” Further, it states that the large mammals shall be “managed in accordance with wildlife management principles to expand the herd and support the establishment of Buffalo within their traditional homelands.”

For Baldes, the pieces are now in place to actually change how bison are classified and, in turn managed, on a Yellowstone-sized swath of west-central Wyoming.

“The next step will be to go to the Inter-Tribal Council, show the two resolutions, and provide the language that could be inserted in the game code,” Baldes said Thursday. “I think that’ll be a pretty smooth step.”

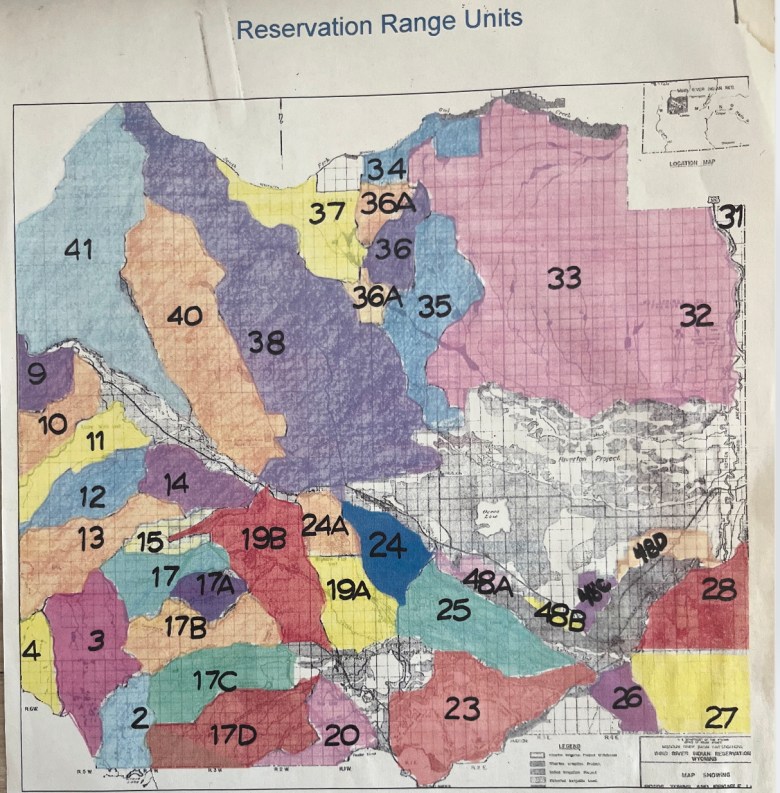

Range units on the Wind River Indian Reservation. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile/photo of physical map)

Range units on the Wind River Indian Reservation. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile/photo of physical map)

The change of classification won’t necessarily flip a switch overnight, be emphasized. As wildlife, bison will only roam designated habitat — and acquiring that land remains a work in progress. Of the reservation’s 54 range units, only two have been designated for buffalo by tribal leadership, Baldes said.

Still, a change to managing bison as wildlife is important because it’ll mark the end of an era of treating the native species as a farmed, domestic animal — the standard today. After the reclassification occurs, the Wind River Indian Reservation could eventually be among the few places in Wyoming and the West where the United States’ national mammal is allowed to roam the landscape with the protections offered by the wildlife tag. In the 19th century, the American bison was hunted to near extinction as part of the genocide of Indigenous peoples, who depended on the migratory mammals.

Although brought back from the brink primarily at Yellowstone National Park’s Lamar Buffalo Ranch, the overwhelming majority of bison alive today are farmed, and many states classify the species as livestock. According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, only about 19,000 American Plains bison broken into 20 herds are large and free-ranging enough to be “subjected to the forces of natural selection.” It’s a tiny fraction of a percent of the tens of millions that existed before Anglo settlement of the West.

In Wyoming, buffalo roam free as wildlife in the roughly 5,000-animal Yellowstone bison herd — the largest such population in the country.

Some older cow bison lead the herd in the breakout from Grand Teton National Park pastureland to U.S. Highway 191 in early 2019. (Angus M. Thuermer Jr./WyoFile)

Some older cow bison lead the herd in the breakout from Grand Teton National Park pastureland to U.S. Highway 191 in early 2019. (Angus M. Thuermer Jr./WyoFile)

In the late 1980s, the Wyoming Game and Fish Commission also created regulations that classified bison as a wild big game species, so long as they dwelled in a designated area for the roughly 500-animal Jackson Herd that now encompasses Teton, Lincoln and Sublette counties. But elsewhere in the state, with the exception of the unoccupied Absaroka herd unit east of Yellowstone, bison aren’t considered wildlife but instead “privately owned or bison running at large.”

The former bison-are-livestock classification on the reservation was similar. Now, it’s likely soon to change on tribal land within the Wind River Indian Reservation, which encompasses about 2.2 million acres.

Baldes is excited: “It’s a big deal,” he said. “It’s substantial that we’re able to reconnect, restore and bring that reciprocal relationship back to our people and communities.”

Still, once again he cautioned that any on-the-ground changes would occur methodically and slowly — and bison wouldn’t roam free overnight.

“This will pertain to the buffalo in designated areas,” Baldes said. “We’ll have to continue working with [grazing] permittees and the tribes and [the Bureau of Indian Affairs] to continue retiring cattle permits.”

There have been no cattle permits retired to create buffalo range to date, he said, and much work remains.

Editor’s note: Jason Baldes is married to Patti Baldes, who’s a member of WyoFile’s board of directors. The volunteer positions have no say in WyoFile’s editorial process. This story has been amended with additional information about the implementation of managing bison as wildlife on the Wind River Indian Reservation.

This article was originally published by WyoFile and is republished here with permission. WyoFile is an independent nonprofit news organization focused on Wyoming people, places and policy.

Related