Tristan Duke takes glacial ice, left, and sculpts it into optical lenses that can be used to capture images such as the one seen on the right.

Tristan Duke takes glacial ice, left, and sculpts it into optical lenses that can be used to capture images such as the one seen on the right.

Sometimes photographers are forced to rush their shot as the scene changes in front of them. But imagine if the very camera they were using was literally melting, forcing the photographer to hurry before their equipment disappears entirely.

That is the challenge faced by Tristan Duke who, among many other things, is a Los Angeles-based experimental photographer sculpting his own ice lenses made from glacial ice to capture truly unique images.

Duke tells PetaPixel that he got the idea for ice lenses after seeing a Japanese ice press — a mixologist tool that shapes ice into specific shapes — in action. He immediately designed and built his own custom ice presses, specifically engineered for optics.

“Every ice lens is different,” Duke explains. “Its qualities shaped by the purity and structure of the ice. But even a single lens keeps changing as I work with it. As it melts, its focal length shifts (becoming more myopic), and new distortions begin to emerge.”

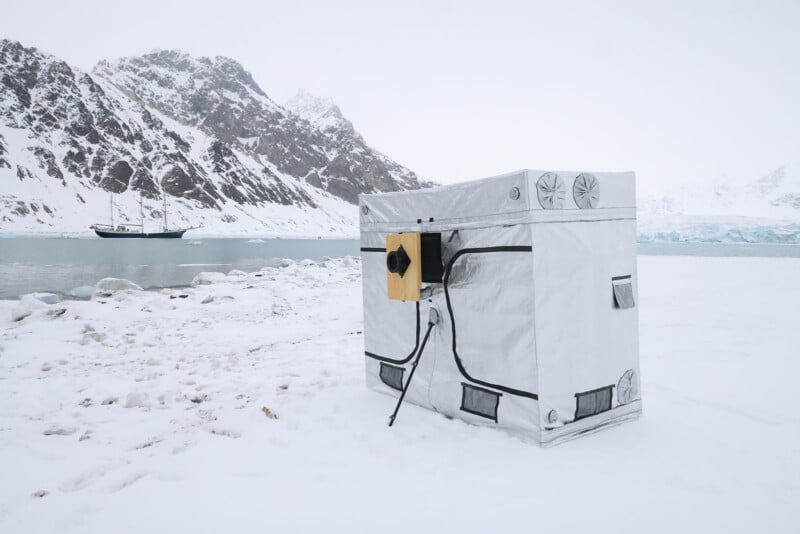

Duke built a large tent that acts as a camera obscura which the ice lens is attached to.

Duke built a large tent that acts as a camera obscura which the ice lens is attached to.  The images are often dreamy and abstract because the melting ice creates random effects.

The images are often dreamy and abstract because the melting ice creates random effects.

Duke enjoys this uncertainty as he is constantly having to adapt, change plans, and improvise in the field when things don’t go as expected. “There’s definitely a kind of surrender in working this way. It becomes a collaboration with the elements — and with the glacier itself,” he says.

While in the Arctic Duke built a large camera obscura in the form of a tent. Inside he hung an enormous 42 x 100-inch paper negative which records the image when the focused light hits it.

“Working with this giant camera in Arctic conditions was relentlessly challenging,” Duke says. “Every day, I loaded nearly 200 pounds of equipment into a Zodiac [Nautic], landed on the ice, hauled everything overland to a location, set up the tent, shaped the ice lens, hung the film — and all of that just to take a single shot.”

Fitting the ice lens.

Fitting the ice lens.  Rolls of photographic paper.

Rolls of photographic paper.  Camera obscura film photo taken on an ice lens. Taking Ice Lenses Out of the Arctic

Camera obscura film photo taken on an ice lens. Taking Ice Lenses Out of the Arctic

For the ice lenses to work, they actually have to be melting. If the lens is too frozen, then it will frost up. Duke was worried that when he went to the Arctic it would be too cold for his idea to bear fruit but thanks to a record heat wave when he was there, he was just about able to prevent frosting.

“In a bitter twist, the project was made possible by global climate change,” he says. He also dipped the ice lenses into salty seawater to encourage melting.

He later took his ice lenses to warmer climates, including Colorado in the wake of the state’s most destructive fire ever. It was the hottest conditions he has worked in with the ice lens.

“I wanted to connect the dots between rapidly melting glaciers, megadroughts, record heatwaves, and increasingly destructive wildfires,” Duke says of his work documenting the aftermath of the Marshall Fire.

“During that shoot, it was over 100 degrees, and inside the tent camera, it felt like an oven. The lenses were melting so quickly, I could barely take a single shot before they disappeared.”

The aftermath of the Marshall Fire in Colorado.

The aftermath of the Marshall Fire in Colorado.  The Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak Fire in New Mexico.

The Calf Canyon/Hermits Peak Fire in New Mexico.

That connecting the dots, as Duke puts it, is a big reason for embarking upon the project in the first place. The literal melting of his ice lenses is a poetic metaphor for disappearing glaciers — an issue the world knows about but one that Duke says people struggle to truly process.

“I’ve collaborated with many climate scientists on this project, and they all tell me the same thing: we know what’s happening, the science is clear — but society isn’t acting fast enough to make the necessary changes,” he says.

“This, I believe, is where art comes in. We urgently need new perspectives and new stories — ones that can shift how we see ourselves in relation to the world.”

As well as wildfires, Duke has also photographed an eclipse with a melting ice lens which “creates strange aberrations.”

As well as wildfires, Duke has also photographed an eclipse with a melting ice lens which “creates strange aberrations.”  Mojave Wind Farm in California. A Song of Ice and Fire

Mojave Wind Farm in California. A Song of Ice and Fire

The work that Duke is doing appears to be entirely novel. But there is historical precedent: “The earliest reference to an ice lens comes from the Chinese alchemist Zhang Hua, who, in the year 290, described using a ball of ice to focus sunlight and ignite mugwort tinder — much like using a magnifying glass to start a fire,” Duke says.

Throughout history, ice lenses have been associated with kindling flames — sparking fascination as to how ice can create fire.

“What’s curious is that in every historical reference I’ve found, the ice lens is always used as a tool for making fire,” Duke says. “The alchemical idea of uniting opposites — fire born from ice — surely made it symbolically irresistible, even mystically significant. Still, it’s surprising that ice lens photography didn’t emerge sooner.”

Wherever Duke goes with his camera obscura, he likes to use glacial ice from a local source. However, he has collaborated with the National Science Foundation Ice Core Facility (NSF-ICF) for some projects which provided him with sections of ice cores to shape into lenses.

“For much of the fire-related work, I used clear ice made from local water sources — emphasizing the connection between fire, drought, and falling water tables in the American West. I often travel with a cooler bag, and in case you’re wondering—yes, you can carry ice on an airplane. As long as it’s fully frozen, it counts as a solid.”

Duke standing in the Main Archvies at the NSF-ICF in Lakewood, Colorado.

Duke standing in the Main Archvies at the NSF-ICF in Lakewood, Colorado.

Duke hopes to continue shooting with ice and is currently working on a series focused on disappearing alpine glaciers, particularly those in California’s Sierra Nevada. He is also hoping to make it to Antarctica one day.

“At the same time, I’m eager to shift my focus toward other experimental projects—designing new cameras, creating optical installations, and developing other devices of wonder,” he adds.

Duke has just released a book, A Brief History of Ice Lenses, Tristan Duke: Glacial Optics, Radius Books, Santa Fe, 2025.

Image credits: Photographs by Tristan Duke