Will you chip in to support our nonprofit newsroom with a donation today?

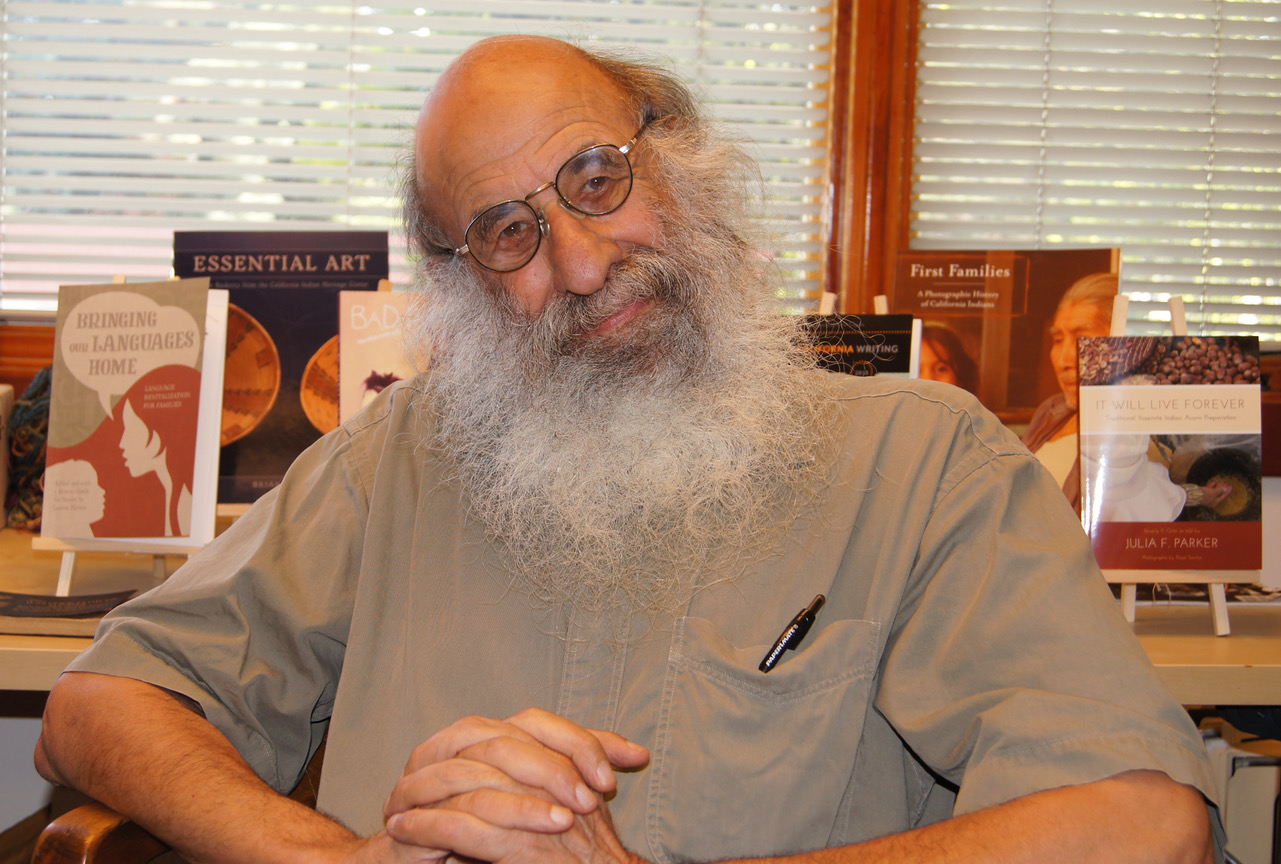

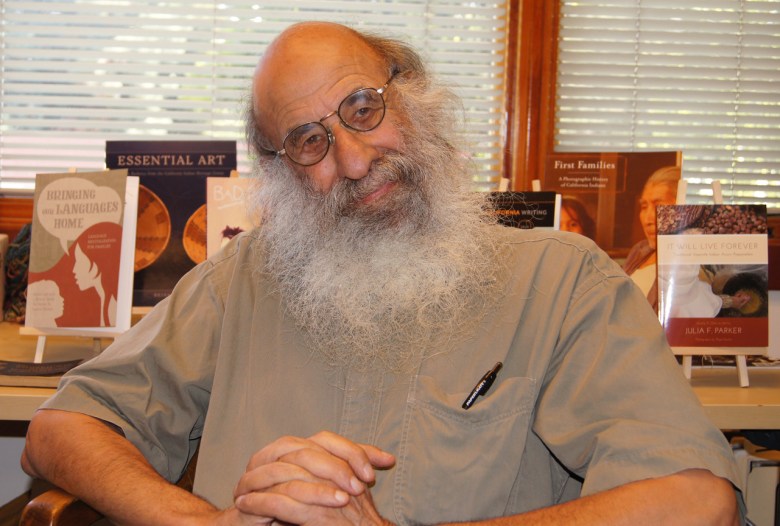

Malcolm Margolin in his office at Heyday Books on University Avenue, circa 2013. Credit: Richard Nagler for Berkeleyside

Malcolm Margolin in his office at Heyday Books on University Avenue, circa 2013. Credit: Richard Nagler for Berkeleyside

Malcolm Margolin, who founded the Berkeley-based Heyday books in 1974 and helped turn it into an outlet for Native Californian writing, died from complications from Parkinson’s disease on Wednesday. He was at Alta Bates Summit Medical Center in Berkeley, surrounded by his family. Margolin, who had been living in a skilled nursing wing at Piedmont Gardens in Oakland since the spring of 2023, was 84.

“The death of Malcolm Margolin leaves all of us at Heyday, the independent, nonprofit publishing company he founded more than fifty years ago, saddened beyond measure,” said Steve Wasserman, Heyday’s current publisher. “It is with surpassing grief that we mark the end of this extraordinary man, but we are summoned to continue the legacy he has left us — a profound commitment to celebrating the beauty and joy to be found in this broken world, a deep and abiding respect for California’s indigenous traditions that he did so much to learn from and explore, a passionate engagement with the issues of social justice he sought to bring to light and, where possible, to heal and repair. Above all, we will miss his unrivaled talent as a storyteller and a dreamweaver. I shall personally miss his constant encouragement and his exemplary curiosity about the world. A mighty redwood of a man has fallen.”

“He was a collaborator and a muse,” said Berkeley-based photographer Richard Nagler, whose two photography books were published by Margolin. “We will never be able to replace a man of such dimensions. He represented and nurtured the best in all of us. His death is a terrible loss for Berkeley, the Bay Area, and the world.”

One of Berkeley’s best-known characters

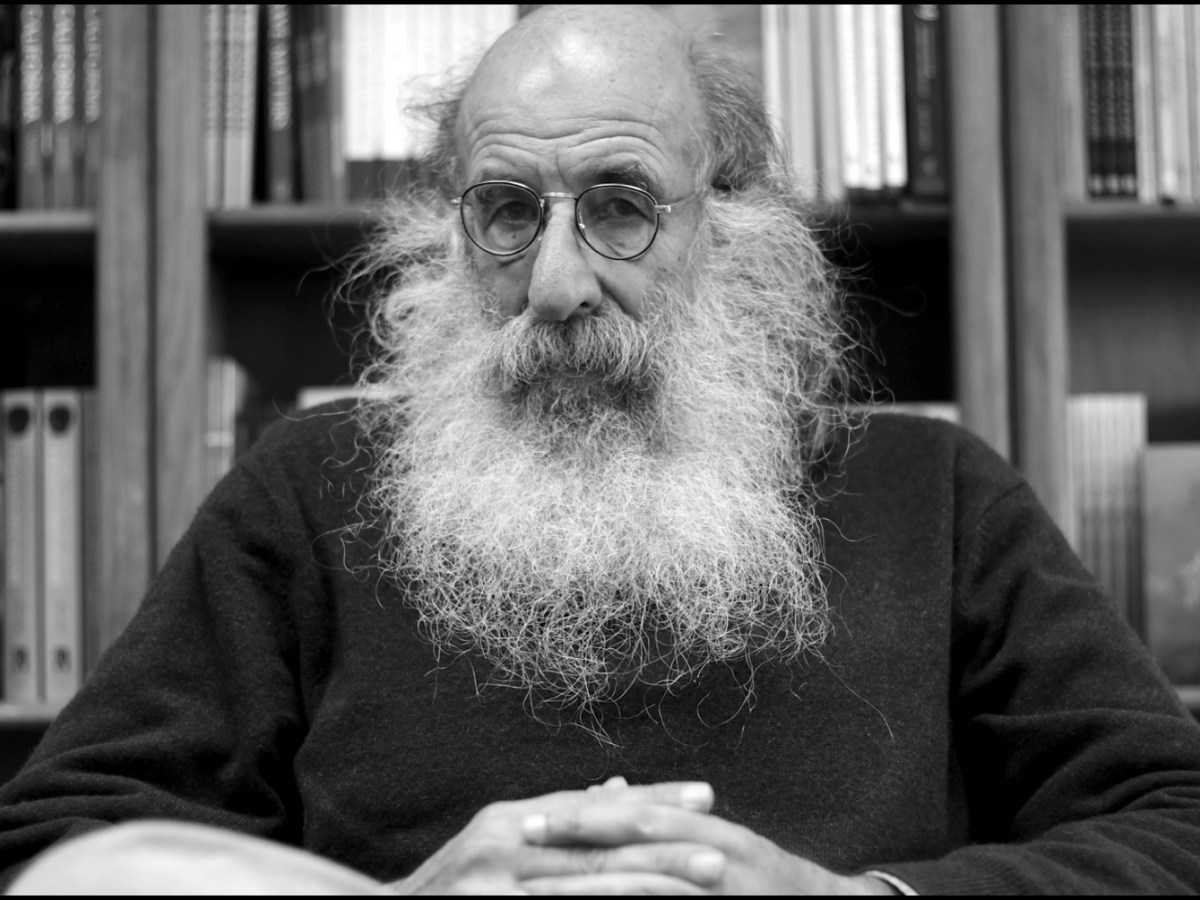

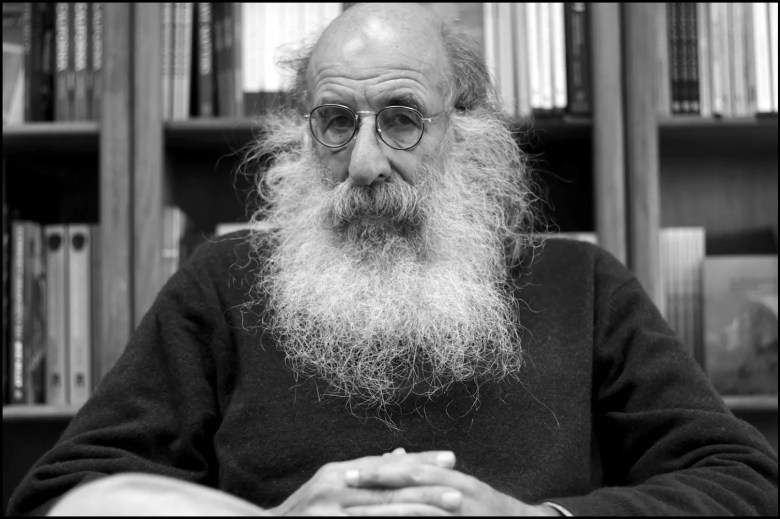

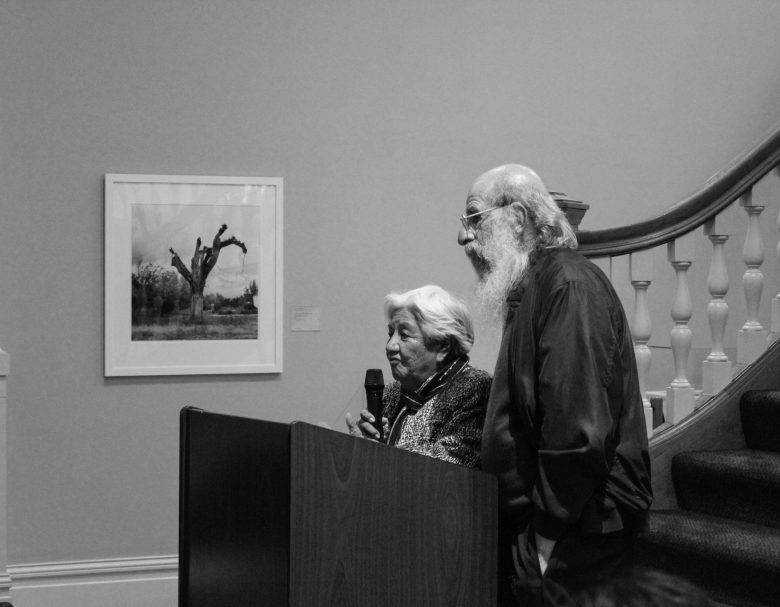

Malcolm Margolin, seen here in 2012, was a fixture at cultural events and an ex-hippie who never gave up the ethos of his generation. Credit: Pete Rosos for Berkeleyside

Malcolm Margolin, seen here in 2012, was a fixture at cultural events and an ex-hippie who never gave up the ethos of his generation. Credit: Pete Rosos for Berkeleyside

With his John Lennon glasses and the rabbinic beard he’d sported since the 1970s, Margolin has stood out over the decades as one of Berkeley’s best-known and easily identifiable characters, a fixture at cultural events and an ex-hippie who never gave up the ethos of his generation. Margolin created Heyday during the height of Berkeley’s independent publishing scene in 1974, and he ran it in a loose and unconventional style — often at a deficit.

Over the course of his tenure at Heyday, Margolin served as its publisher, executive director and one of its authors. He retired from Heyday in 2015, at the age of 75.

A lover of other people’s stories, Margolin was described by the writer Rebecca Solnit as “the uncle you wish you had,” a people person known for his unconventional approach to the business of publishing. He saw his role as one of a bridge builder, “reaching out and taking risks to build connection across communities, to take risks with the books he brings to print,” oral historian Kim Bancroft wrote in The Heyday of Malcolm Margolin: The Damn Good Times of a Fiercely Independent Publisher, a collection published in 2014 to coincide with the imprint’s’s 40th anniversary.

He’s the uncle you wish you had.

Author Rebecca Solnit

“Malcolm’s most valuable support went to Indigenous California, through the magazine News from Native California, through the books by and about Indians in California, but also through his support — and that of Heyday’s — to many Native cultural organizations, such as the California Indian Basketweavers,” Bancroft wrote in a March 2024 email. “Malcolm would show up, with or without his Heyday books, at Powwows, Big Times, and friends’ salmon feasts in order to, as he said, ‘warm himself at the hearth of others’ stories.’”

A young traveller who embraced the Summer of Love

Margolin was born on Oct. 27, 1940, in a Jewish neighborhood in Dorchester, outside Boston, the son of Rose and Max Margolin, a freight broker.

He went to Harvard University in 1958, where he majored in English, but wouldn’t graduate until 1964, dropping out a couple of times, much to his father’s chagrin. During such hiatuses, he lived in New York and worked for his father’s employer in Puerto Rico. He described his college years, in which he slowly acquired social skills, as being in a “cocoon more than I was getting wings.”

At Harvard he met his future wife, Rina, a clinical psychology major at Radcliffe College. After graduating in 1964, he moved back to Puerto Rico where Rina joined him. They were married in 1966 and lived on the Lower East Side of Manhattan until February 1968, when they left to spend several years criss-crossing the continent, with stops in, among other places, California, Mexico and Canada.

In 1967, they stopped in San Francisco for the Summer of Love, where he found “such a wonderful sense of openness.” In 1968 they abandoned their East 10th Street walkup because Rina did not think New York City was a place to raise kids. One of his neighbors urged him not to leave, arguing that he would become a great writer if he remained in New York.

“In New York I might have gotten a much greater reputation; perhaps I might have been world famous,” he writes in The Heyday. But I also thought about how shallow greatness is in New York — how it depends on reputation. What this place, what Heyday has allowed me to do is to create a real community, to be really useful, to create a home for certain people and certain ideas.”

The couple sold everything and headed west again, this time in a VW bus Margolin bought for $300 in Queens. In California, they lived in a campground in Big Sur for a couple of months, hiking everywhere, learning about local plants and living off wild foods. With a typewriter in the back of the bus, Margolin began writing about forests and forestry. During this period his articles were published in Science Digest, National Parks and The Nation magazine.

‘Married to Berkeley and fell in love later’

Malcolm Margolin and his children, Sadie and Reuben, in an undated photograph. Credit: Heyday archives, reproduced in The Heyday of Malcolm Margolin by Kim Bancroft

Malcolm Margolin and his children, Sadie and Reuben, in an undated photograph. Credit: Heyday archives, reproduced in The Heyday of Malcolm Margolin by Kim Bancroft

In 1970 they settled in Berkeley, where Margolin had some college friends, pending the arrival of their first child. He wrote that it was a place he thought he would stay for a few months before wandering again.

During a March 2024 interview with Berkeleyside at Piedmont Gardens, Margolin rephrased a quote from the writer Chitra Banerjee Divakaruni: “In America you fall in love and then get married. In India, you get married and then you fall in love.”

“I got married to Berkeley and fell in love later,” he said with a smile.

In June 1970 the couple moved into a small apartment at Bancroft Way and Acton Street, which they rented for $90 a month. Their son Reuben was born later that year. His middle name was Heyday.

In the first years of Reuben’s life, the couple would live in about 11 places in Berkeley, as well as in a tent at a campground in Anthony Chabot Regional Park for four or five months, an experiment in living close to the land, which he admitted must have been lonely for his wife. By that time (1970-72), Margolin was working as a groundsman for the East Bay park district, doing everything from cleaning up picnic areas to building trails and leading nature walks for kids.

Heyday is born — after several rejections

His work in the parks formed the basis of two books: The Earth Manual, How to Work on Wild Land Without Taming, which was published first by Stewart Brand’s Whole Earth Catalog in 1972, and then by Houghton Mifflin in 1975; and East Bay Out: A Personal Guide to the East Bay Regional Parks, which, in 1974, became Heyday’s first title.

Margolin had originally pitched the book to local independent publishers, which were flourishing at the time. Berkeley’s Ten Speed Press found the book too regional. Poetry publishers found it too information-heavy. So Margolin created his own independent press, naming it after his son’s unusual middle name, what Margolin said was part of a hippie tradition at the time.

“I thought I’d publish a book and then go on and do other things,” Margolin writes in The Heyday. “I never thought I’d be a publisher.”

In addition to writing the book, Margolin designed, laid out and distributed it himself, a process he said made him a better person.

“There was something in making those decisions, in doing something real, that was very energizing and fulfilling, very self-gratifying,” he writes in The Heyday. He didn’t like the “rebellious, surly” person he was otherwise, who covered up his inadequacies with belligerence. But “I liked the person who was a part of this creative force, moving something out into the world, creating something through love and respect, giving it off to the world.”

‘The Ohlone Way’: groundbreaking and controversial

During the 1970s, a golden age of Native American activism, Margolin began to wonder about the Indians from Northern California. At the time, no one had ever done a comprehensive look at Bay Area tribes from a non-anthropological perspective.

Though he wrote that he was always self-conscious about “being a white guy writing about Indians,” that didn’t stop him from doing so. He spent almost three years researching the groundbreaking book The Ohlone Way: Indian Life in the San Francisco-Monterey Bay Area (1978), mostly by perusing the collections of UC Berkeley libraries. In the book’s afterword he writes that by the end of his research he had met only a few Ohlone families.

“Because of the element of speculation,” he writes in the book’s introduction, “this book is not so much about what Ohlone life was like, but rather about what Ohlone life may have been like.”

The San Francisco Chronicle considers the book “one of the hundred most important books of the twentieth century by a western writer.” Alice Walker blurbed it as being “beautifully imagined and written.” The American Anthropologist said Margolin had “written thoroughly and sensitively of the Pre-Mission Indians in a North American land of plenty.”

As a writer and publisher, I have no choice but to acknowledge the right of a conquered people to control, or at least influence, the telling of their story and the need for that story to be heard.

Malcolm Margolin

Margolin wrote he hoped that, at readings or lectures, Ohlone people would buy a copy of the book and perhaps share their knowledge and memories.

“The publishing industry on the East Coast has largely ignored California Indians and their stories,” said Greg Sarris, a Heyday author who is chairman of the Federated Indians of Graton Rancheria, headquartered in Rohnert Park. “It is Malcolm who got our stories out there so early.”

Sarris said The Ohlone Way was important because it reached many, many non-Native people in California and elsewhere. “The book woke up the public and got the public talking. California Indian people have since taken up the pen themselves and have been busy writing our stories.”

However, not all Native people or members of the Ohlone Indian Tribe embraced the book. At a reading shortly after the book was published, Margolin was met by members of the American Indian Movement who asked, “Why are you writing about our people?”

Andrew Galvan, an Ohlone elder, and his cousin, Vincent Medina, who had worked at Heyday under Margolin, voiced their displeasure in April 2024. They complained that the book did not properly credit Ohlone sources and its illustrations made the Ohlone people appear “less than.”

Margolin has addressed similar complaints from the Native community several times in print, including an afterword he added to The Ohlone Way in 2003.

“As a writer and publisher, I have no choice but to acknowledge the right of a conquered people to control, or at least influence, the telling of their story and the need for that story to be heard,” he wrote. “These are complex and important issues and my struggling to sort them out has defined much of what has been happening to me in the last 25 years.”

Book prompted groundswell of writing about native cultures

Malcolm Margolin stands next to Joanne Campbell as she blesses the Heyday Harvest celebration in her Coast Miwok language, California Historical Society, San Francisco, 2012. Credit: Yuliya Goldshteyn, Heyday archives, reproduced in The Heyday of Malcolm Margolin by Kim Bancroft

Malcolm Margolin stands next to Joanne Campbell as she blesses the Heyday Harvest celebration in her Coast Miwok language, California Historical Society, San Francisco, 2012. Credit: Yuliya Goldshteyn, Heyday archives, reproduced in The Heyday of Malcolm Margolin by Kim Bancroft

The Ohlone Way began a groundswell of writings by and about California native cultures that Heyday published, including It Will Live Forever (1991) by Beverly R. Ortiz as told by Julia F. Parker; Alcatraz! Alcatraz! (1992) by Adam Fortunate Eagle; and Flutes of Fire (1994) by Leanne Hinton. More recently, the award-winning Bad Indians: A Tribal Memoir (2012) by Deborah A. Miranda has literally helped rewrite the history of Native peoples in California, and is frequently taught in the fourth grade as part of the state curriculum and in classrooms throughout the U.S.

Margolin himself would go on to write The Way We Lived: California Indian Reminiscences, Stories, and Songs (1981) and Deep Hanging Out: Wanderings and Wonderment in Native California (2021).

In 1987, he launched News from Native California, which was initially envisioned as an events calendar but quickly became a more comprehensive magazine.

Shortly after getting News of Native California and the Native California Network going, Margolin was instrumental in establishing a language conference that brought together the last speakers of California languages. That led to a master-apprentice program called Advocates for Indigenous California Language Survival, founded in 1997, a Native-run and led organization devoted to implementing and supporting the revitalization of indigenous California languages.

In 2012, Margolin established Heyday’s Berkeley Roundhouse program, which promotes the work of Native Californian writers.

Margolin was active until the end, attending public events and posting to his Facebook as recently as Aug. 5. He was at the Brower Center in downtown Berkeley on June 23 for an event centered on a new biography of John Muir, Cast out of Eden, by Robert Aquinas McNally. He was organizing his papers and still writing, and had expressed his excitement about the turning over of a 2.2-acre Ohlone shellmound site in West Berkeley to a Native land trust.

Earlier this year, when asked by Berkeleyside about the rise of Indigenous activism and its many successes in recent years, Margolin said, “I never thought I’d see it in my lifetime.”

Margolin, much lauded, said he had no regrets

Malcolm Margolin at an event marking Ohlone Park’s 50th anniversary, June 1, 2019. Credit: Pete Rosos

Malcolm Margolin at an event marking Ohlone Park’s 50th anniversary, June 1, 2019. Credit: Pete Rosos

In addition to serving as an advisor and mentor to other publishers, Margolin co-founded the Alliance for Traditional Arts, devoted to California folk arts, in 1997 and the Islandia Institute, a literary center in Riverside, in 2001. In the fall of 2017, he established the California Institute for Community, Art and Nature.

Realizing that he would be unable to lead Heyday because of Parkinson’s, Margolin wrote in 2014 that he would need a successor. In 2016, the Heyday board hired Wasserman, a veteran of the publishing industry, to take the helm.

In 2014 Margolin described his Parkinson’s as “the elephant in the room. I’ve tried to camouflage the elephant as if it were a sofa, but it’s not fooling anybody. It seems wrong not to mention it, but I don’t like having people feel sorry for me. I don’t like people helping me. So I don’t focus on it.”

Over the years, Margolin was recognized with numerous awards. In 2012 he was the second person in the U.S. to receive the chairman’s commendation from the National Endowment for the Humanities. He received a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Bay Area Book Reviewers Association, a Community Leadership Award from the San Francisco Foundation, a Gold Medal from the Commonwealth Club of California, an American Book Award from the Before Columbus Foundation and Cultural Freedom Award from the Lannan Foundation. At Heyday’s 50th anniversary celebration, held in October 2024, Margolin was honored by the imprint he founded with a Lifetime Achievement Award.

Looking back, Margolin wrote that he had no regrets. “I’m proud of what I’ve done. I can’t imagine having done any better or being any more content or more proud or more at home with what I’ve done.”

Margolin is survived by his wife, Rina, son Reuben and a daughter, Sadie Costello, all of Berkeley, son Jacob of Houston, Texas, and five grandchildren. His brother, William, of Randolph, Mass., died on July 22. The family has not yet released details about a memorial service or donations.

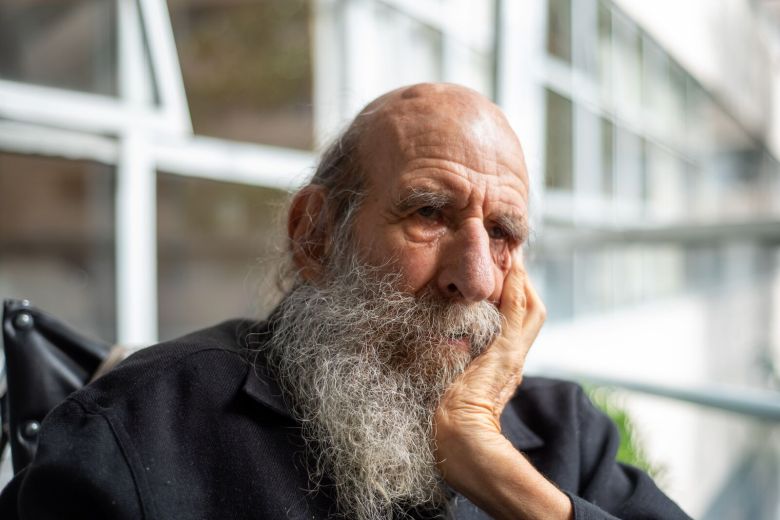

Malcolm Margolin photographed at his assisted living home in Oakland, March 4, 2024. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight

Malcolm Margolin photographed at his assisted living home in Oakland, March 4, 2024. Credit: Ximena Natera, Berkeleyside/CatchLight

Related stories

Heyday books at 50: The page-turning tale of a Berkeley original

May 7, 2024May 9, 2024, 12:48 p.m.

Heyday names Steve Wasserman as new publisher

February 18, 2016Aug. 20, 2025, 4:23 p.m.

Snapshot: Malcolm Margolin, Founder, Heyday Books

January 11, 2012Oct. 4, 2022, 12:58 a.m.

We know that most readers don’t get to the end of the article. But you did! To support our in-depth, rock-solid reporting, please consider making a donation to our nonprofit newsroom today. We rely on our readers — particularly the ones who read the whole story!

“*” indicates required fields