Peter Orner keeps a small writing studio inside an old hotel on the Connecticut River, where Vermont meets New Hampshire. That room, to put this kindly, is often a landfill, a mess, though not without raw charm. The hotel dates to the 1920s, some artists work here, some people live here. The neighborhood has a drug problem. Orner wades to his desk, he doesn’t walk to his desk. He steps across papers and books. On a wall is some research he did for his latest book, though if you didn’t know he was a writer, you might assume from its pastiche of photos and news headlines that he was a conspiracy nut. He’s embarrassed when friends visit, but all of it works for him.

Across the river is Dartmouth College, where he teaches, and he’s never been comfortable with its Ivy League comforts. His studio is a retreat. His window looks out on the red-bricked rear of a restaurant, where staff take smoke breaks.

He misses home, he misses Chicago.

He keeps a row of Chicago books collected on a shelf, the lives and writings of Harold Washington, Richard J. Daley, Jane Byrne, Ben Hecht. He likes to joke, having grown up in Highland Park, “I think of Chicago as being ripped away at birth. It’s become the original sin of my life.”

There’s a whole chapter of Orner’s new novel, “The Gossip Columnist’s Daughter,” in which the fictional narrator, but really Orner — Chicago native son, Highland Park-raised, now homesick and running the English and Creative Writing Department at Dartmouth — just lists the names of the people he misses. Names he’s heard a million times. Chicago names. “It’s their names,” he writes, “we’ll never shake their names.” Some of those names stand alone, some of the names are lumped, and some cascade down the page.

Big Bill Thompson, Mayor Daley, Jesse Jackson.

Bozo.

Oprah.

Ditka.

Ye.

“Through the osmosis of repetition,” he writes, certain names “become part of the permanent vocabulary.” Meaning, certain names in Chicago no longer indicate people so much as a kind of geography, as inseparable from the city as Lake Michigan. Like: Donahue, Payton, Ernie Banks, Ryne Sandberg, Tim Weigel, Buddy Ryan, Buddy Guy, Ray Rayner. But also: Harold Washington, Jane Byrne, Bill Kurtis, Harry Caray, Frazier Thomas, Linda Yu, Butkus, DuSable, Mamet, Cisneros, Terkel, Bellow, Wright, Algren, Belushi, Dybek, Hansberry. Orner lists all of them, and many more.

But one name dominates: Kup, as in Chicago Sun-Times gossip columnist Irv Kupcinet.

For the sake of readers who didn’t grow up entrenched in local lore, Orner’s narrator says: “Chicago didn’t name Kup ‘Mr. Chicago.’ Kup crowned himself. But he repeated it so often, and for so many years, that the city had no choice but to accept it, if only to tune him out a little. Okay, okay, okay, have mercy, you’re Mr. Chicago. Now leave us alone. We’re reading Mike Royko on page 2.”

Orner, 57, was once a sewer worker for the city of Highland Park, for a short time. He’s held other jobs, like professor, distinguished lecturer, volunteer firefighter. He didn’t work in sewers long, but the point is: He knows Midwest tics and trash, intimately. He’s written closely about nearly every place associated with his life: Fall River, Massachusetts; California; Namibia. But his writing never shakes Chicago. When I mentioned to him last spring that “Gossip Columnist” is the most Chicago novel I’ve ever read — and maybe the long-underrated author’s first hit — he wrote back that it was his only way of being where he wishes he lived. It tells the story of a man obsessed with a footnote to local crime history, and how his narrator, like Orner himself, brushes up against that history.

The daughter in the title is Karyn Kupcinet, also known as Cookie, though certainly better known, by anyone who may remember, for being murdered mysteriously in 1963.

It’s a remarkable read, so tricky to parse or summarize, so willing to subvert wherever you think it’s headed, that Stuart Dybek, the Chicago short story writer, and a friend of Orner’s, declined to write a blurb for the novel. He really tried, he told me, but eventually: “It just became too hard to do it justice. Peter’s book is this total cross of fiction, non-fiction, memoir, reporting — and yet! No big deal is made of it! Peter plunges in, but also gives you the standard things to expect from a good story, so reading it is not really startling. It’s not a chore to read. He gets you to accept it. And 95% of writers couldn’t get away with writing like that — 95% of their agents wouldn’t allow it.”

The book’s narrator, a well-respected writer who had never had much success (and sounds not so dissimilar from Orner), explains to the reader, probably shooting himself in the commercial foot, deflating his narrative: “This isn’t a detective story or a police procedural. It’s not a mystery.” And still, at times, the novel that follows and its wandering, punchy plot read exactly like a mystery.

It’s just not about the mystery you think you’re getting.

Months after reading it, I’m still not sure which of the book’s mysteries is the main one. “It’s about personal failure, generational failure, the failure of its characters within the sweep of history,” said Joshua Kendall, Orner’s editor, as well as executive editor of Mulholland Books and Little, Brown. “I also read it as true crime from the vantage of a family secret, but secondly as a Jewish-America comedy — look, it’s incredibly active.”

A wall of book research in writer Peter’s Orner’s office. His latest novel, “The Gossip Columnist’s Daughter,” partly digs into the conspiracy theory that followed the 1963 murder of Karyn Kupcinet, daughter of Chicago journalist Irv Kupcinet. (Alberto Rodriguez)

A wall of book research in writer Peter’s Orner’s office. His latest novel, “The Gossip Columnist’s Daughter,” partly digs into the conspiracy theory that followed the 1963 murder of Karyn Kupcinet, daughter of Chicago journalist Irv Kupcinet. (Alberto Rodriguez)

Here’s the thing about that story: Peter Orner is from a well-connected family. He heard a lot of stories. He knew people. His stepfather, Daniel Pierce, was a Highland Park mayor and a member of the Illinois House of Representatives; his mother, Rhoda Pierce, is still a trustee with the North Shore Water Reclamation District. His grandfather owned an insurance company on Garfield Boulevard on the South Side; its faded awning still hangs over a hair salon. His grandparents were also close friends with Kup and his wife, Esther.

“If you wanted to make it in this country and were a celebrity, you had to go through Chicago,” Orner said, “and if you were going to make it in Chicago, you had to go through Kup. I was fascinated with our connection. My grandfather went on fishing trips with him. (His grandparents) might not have thought of Kup as a serious journalist, but he had staying power.” They were friends when Kup’s daughter was found strangled in Los Angeles, just a week after President John F. Kennedy’s assassination, which, in those hothouse days, and forever after, made Karyn Kupcinet something of an improbable minor figure with conspiracy theorists.

Her murder was never solved, though often glib newspaper accounts from the time paint a promising 22-year-old actress, heartbroken over a boyfriend, possibly suicidal, maybe using drugs.

“All of it ruined her reputation, this kid just trying to make a life separate from her father,” Orner said. “She deserved better. Anyway, around then, there was also a falling out (between Kup and his grandparents). We carried it around, like ‘Whatever happened to that friendship with the Kups?’”

In “Gossip Columnist’s Daughter,” a family that sounds a great deal like Orner’s family (but is fictional, not his family and named the Rosenthals) has a falling out with the actual Kup family. The narrator becomes convinced that their friendship breaking up sowed the roots for his own problems decades later and “hobbled” his family‘s future. But the family themselves (like Orner’s real-life family) had long since moved on.

“The mystery of Cookie’s death led to a lot of questions,” Orner said, “but in writing this, I was most interested in the collateral damage of the aftermath. I was interested in a friendship that ends suddenly. I had heard that when a child dies, friendships can be among the things affected. Your life gets a hole blown through it and friends especially can get expendable in cruel ways. The book is fiction, but then there’s kernels of truth.”

Orner knew Kup a bit.

For a while, he was a sports stringer for the Sun-Times and would run into Kup in the hallways. Orner worked for sports legend Taylor Bell. “He had these owl glasses and he would get scary. I’d be standing at a pay phone in like Glenbrook North or Romeoville or somewhere and would call in a high school football game and wouldn’t be able to describe a touchdown well enough and he would give such (expletive). He would yell: ‘I need texture! I just need more!’ I internalized that. I think he helped me learn to write.”

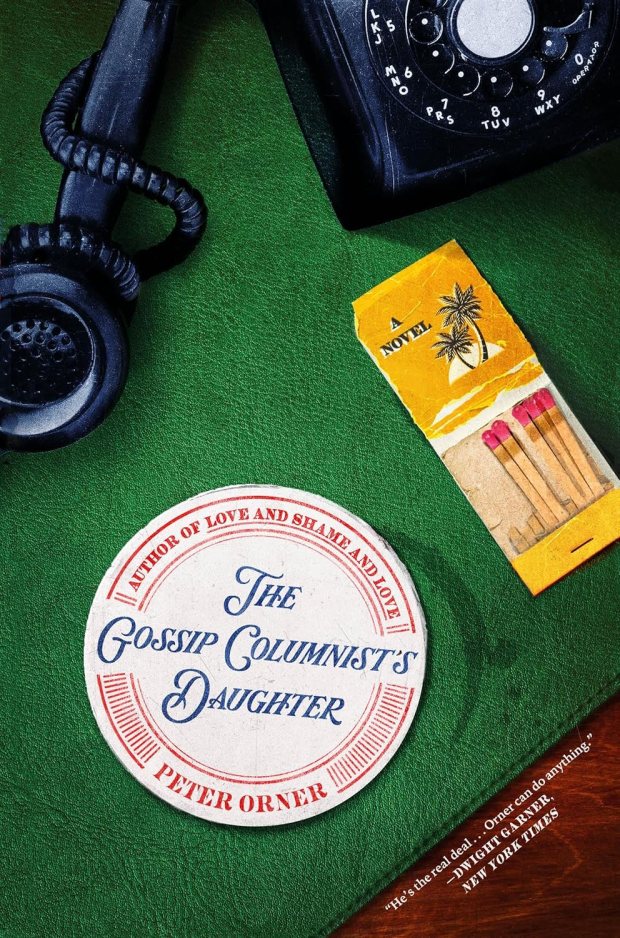

“The Gossip Columnist’s Daughter” by Peter Orner. (Little, Brown and Company / Aug. 12, 2025)

“The Gossip Columnist’s Daughter” by Peter Orner. (Little, Brown and Company / Aug. 12, 2025)

Orner became the quintessential “writer’s writer,” which meant everything that means both good and bad, forever on the periphery of fame, respected but unknown. He had no illusions about that trajectory. He set out to write short stories for a living. He studied with Marilynne Robinson at the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop and taught writing himself for years at San Francisco State University. He was a Fulbright scholar, landed in the New Yorker and won three Pushcart Prizes. He’s also written three novels and three books of short stories; the first, “Esther Stories,” from 2001, even got a shout-out in Kup’s column. If Orner ever received a negative review, I’ve never seen it.

“But the line on him just stayed ‘writer’s writer,’” said Alex Gordon, a Northbrook native and friend of Orner’s since they met as undergraduates at the University of Michigan. “It’s fascinating to me because, without casting sideways glances at other Chicago writers, he’s very accessible. But he’s also never tried to put a finger on the culture in the way someone like, say, his friend Dave Eggers will. Peter’s probably never going to write an AI novel.”

Rather, Orner remains in the lineage of someone like Dybek, another “writer’s writer” from Chicago. “I don’t know if Peter’s really flown under the radar,” Dybek said. “I’m not sure it’s entirely true, but I’m also not sure if people know what an original voice he has.”

Orner once told an interviewer that he imagines himself like a scavenger, circling old memories. That speaks to the casual drift of his prose. His sentences — “utterly focused on every line, and it’s rare to meet a writer anymore who is thinking through every word and line,” Kendall said — have a comfortable bittersweet fogginess that snaps into view around strange and telling specifics. The way Rosehill Cemetery is practically a neighborhood unto itself, yet somehow easy to drive by without really noticing. The way a person can be so striking that they look like a “myth.” The way Ricardo Montalban was once a routine signifier of class. The way the Drake Hotel used to freshen its bathrooms by leaving fresh fruit in the urinals. You never know where his paragraphs will leave you.

In conversation, Orner describes what little he knows of his family’s relationship with the Kups as “bread crumbs of our history,” ones he follows through his novel, fictionalizes in places, but also, the kind of bread crumbs he doesn’t want to become forensic about. He doesn’t want to know exactly why his grandparents and the Kups stopped speaking.

“All I know is something happened 60 years ago there and it’s been in my head for so long, I wanted to play it all out in fiction. Which is not the first time I have used family in fiction. A lot of writers, of course, do that. My hero, Isaac Babel, would say never make something up, there is no need for that. But of course I make (expletive) up. There is too much for me to figure out using fiction. I can’t resist. In the past, I’d get harsh about this with family: ‘Look, this is what I do for a living!’ But my father, who passed away 10 years ago and takes a lot of hits in my work, which he deserved — I treated him roughly, but he also knew the difference between fiction and nonfiction.

“He helped me figure this out. We need to tell the stories we avoid. We need to go there. So I go back into 1963, to say the things that maybe we aren’t supposed to say.”

cborrelli@chicagotribune.com