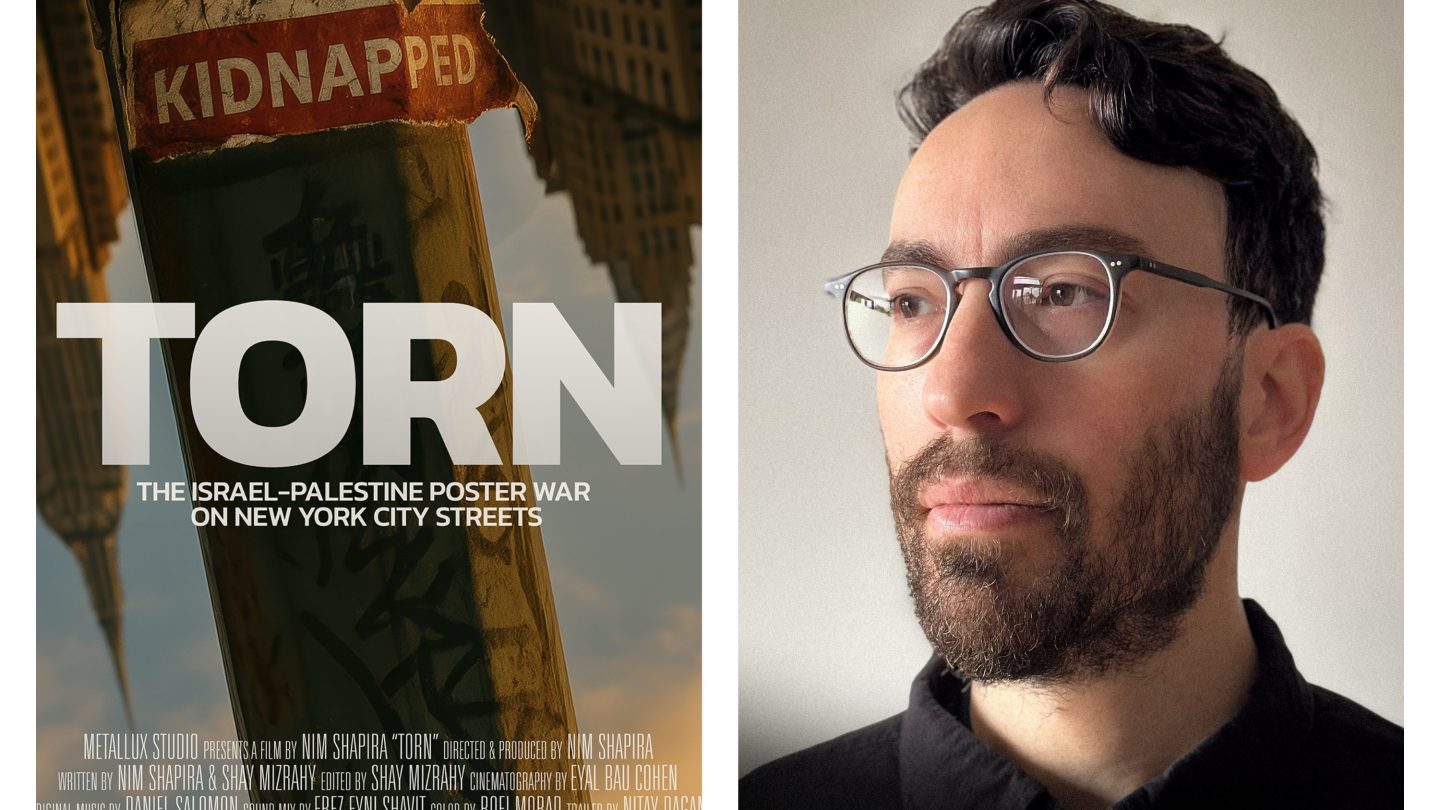

In the days following the Oct. 7, 2023 attacks on Israel, posters featuring the 251 people kidnapped by Hamas began popping up on the streets of New York. Just as quickly as the mysterious posters appeared, they began being torn down. Amidst the chaos and anger, Nim Shapira, an American-Israeli filmmaker based in New York, took to the streets to document the clashes between those who wanted the posters up, and those who wanted them gone.

The result is the documentary Torn, which will bow on Sept. 5th in New York and Sept. 12 in Los Angeles – with more cities to be announced. For Nim, the film isn’t about the geopolitical conflict in the Middle East. He deliberately keeps footage of Oct. 7th and the war in Gaza to a minimum. It’s a film that doesn’t offer answers; it asks questions.

“It zigzags between hostage families, protests, social media feeds, rabbis, activists, civil libertarians, and people doxxed for tearing posters down, while layering in news coverage from across the spectrum, from Al Jazeera to Fox News,” notes Nim of his film. “My goal was to capture the city’s raw cacophony—alive, grieving, angry, divided– so the film feels immediate, messy, and contradictory, just like New York itself.”

In a conversation with The Hollywood Reporter, Nim explains why he turned his lens away from the conflict in the Middle East and focused on the conflict manifesting on the streets of New York.

This film covers a controversial topic. What do you have to say to those who would refuse to see your film?

If people see this is a film made by an American-Israeli about Jewish pain, some would say, “I don’t want to see this film.” This film is much more than that. It’s a film about compassion, it’s about freedom of speech, it’s about competing narratives. And I would love for everyone to see it.

For me, this is about the hostages, and I think this is something that every Jewish person will tell you: “It could have been us.” It could have been us vacationing in Israel or sleeping in an Airbnb in south Israel or going to a party. So I saw my face in every hostage. Many Jews were really hurting and society didn’t choose to see them or see their pain.

That being said, now more than ever, I will say that Israelis are not Netanyahu and Gazans are not Hamas. I really believe that the only way forward is coexistence, and to do this we need to communicate. Hopefully my film can help this process.

What has been the most impactful moment for you to see in the upcoming release of Torn?

This is an independent film, and I’m very proud of the number of screenings I’ve had so far. I’m very proud of us releasing it in New York and L.A. And when I say us, it’s me and my small team.

I was able to screen the film in many different places, and help create dialogue between people who wouldn’t have otherwise listened to each other. I remember one of the most meaningful screenings was in Berkeley, in a private home with 20 people: half Trump voters, half Kamala voters. Instead of taking questions like I usually do, I just listened. They argued, they listened, they wrestled with one another. That’s what this film is for. Jewish audiences often come in with grief and recognition, while other audiences bring their own traumas – different, but equally valid. What amazes me is how the same film sparks such different conversations, depending on the room. Most importantly, they didn’t agree with one another, but it was a magical moment, and I was proud to see their dialogue.

Why was it so important for you to make this film?

The most important thing for me was the idea that we couldn’t talk to each other as people. Specifically in this day and age, it’s incredibly important for me to connect with the Palestinian people. Unfortunately, I haven’t been able to connect with them in real life, but online. I have Palestinian friends online, and I talk to them weekly about what’s going on, and we send each other clips, or “Have you seen this?” Or, “What do you think about that?” They share content with me from both Gaza and Israel – stories, footage, perspectives that I may never have encountered otherwise, and I try to do the same for them.

I think that when we don’t have missiles and rockets above our heads, and we’re thousands of miles away from the conflict, the least we can do is to sit down and talk to one another. Or at least listen to the narrative, and we can disagree, but at least listen to one another. For me, in making Torn, one of my most important goals was to break the echo chambers and polarization, and hopefully invite a conversation.

What do you hope people take away after watching your film?

I have three goals: One is for people to understand that empathy is not a limited resource and every person is a soul. Two: I want people to understand that it is possible to hold several truths in your brain. It’s hard, but it’s possible to hold multiple truths because this topic is very complicated. And the third thing is more of a question. Can we have difficult conversations with people that we disagree with?

Before Oct. 7th, I had many friends from the Middle East, I had Lebanese friends and Moroccan friends and these relationships were fractured after Oct. 7th. This film is not a statement, it is an invitation for a dialogue I could not have with them.