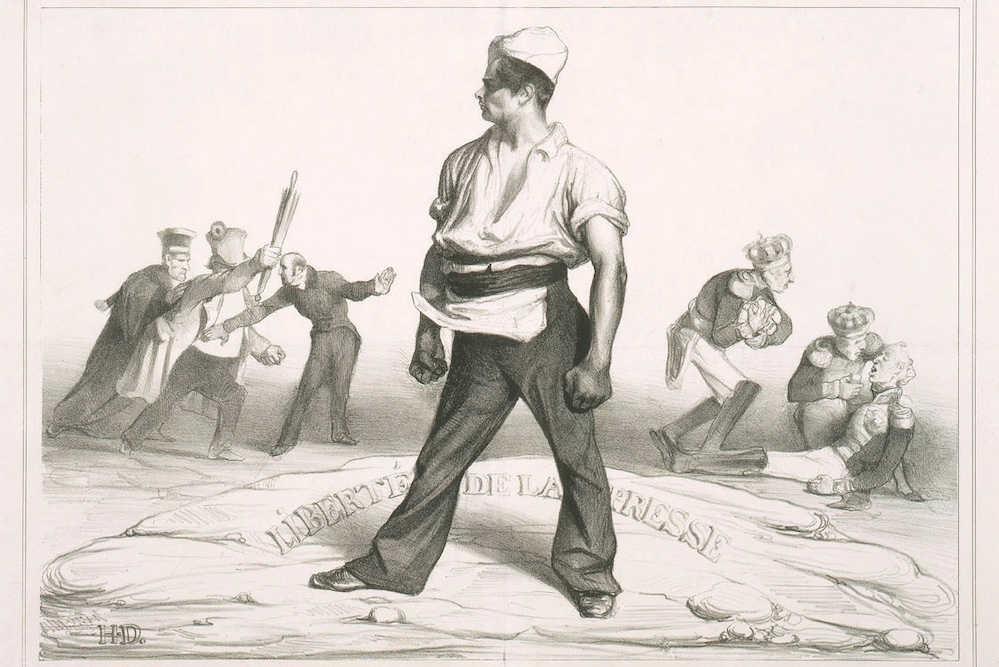

Honoré Daumier’s 1834 lithograph Ne vous y frottez pas!! Liberté de la presse leaves no question where the multifaceted artist stood on the matter of press freedom. Credit: Courtesy Image / McNay Art Museum

Honoré Daumier’s 1834 lithograph Ne vous y frottez pas!! Liberté de la presse leaves no question where the multifaceted artist stood on the matter of press freedom. Credit: Courtesy Image / McNay Art Museum

As the current presidential administration resorts to lawsuits and intimidation to rein in the press, a new McMay Art Museum exhibition examines how an earlier generation of artists defied censorship to offer blistering critiques of those in power.

“Do Not Meddle With It!!: Print Censorship in 19th Century Paris” shows the creative artistry that thrived in 19th-century France despite the government’s attempts to ban politically charged printed images.

Drawn from the McNay’s collection of works on paper — specifically lithographs meant for public display — the exhibition centers around pieces by Honoré Daumier, considered the “Michelangelo of caricature,” and Édouard Manet, the modernist painter who also produced significant print work.

Indeed, the exhibition takes its name from Daumier’s 1834 lithograph Ne vous y frottez pas!! Liberté de la presse, which leaves no question where the multifaceted artist stood on the matter of press freedom, even as he endured multiple prison sentences for his work.

“In their own ways, these artists took very heroic stands,” said Elizabeth Kathleen Mitchell, the McNay’s curator of prints and drawings. “What strikes me about this work is the sheer determination of creative minds to express themselves in a time that defying those in power meant time in jail, a loss of personal liberty.”

The exhibition is the first Mitchell has assembled for the McNay since joining the museum in March.

Despite France’s history as a wellspring of artistic innovation, its 19th-century laws required government censors to review and approve all lithographic prints before they could go into production.

Censors not only had the power to prevent works of art from being distributed, according to Mitchell, they could shut down presses, take possession of the heavy lithographic stones used in the process or even order artists’ arrest.

The French state primarily employed those heavy-handed tactics from 1820 to 1881, a period where citizens had no shortage of interest in current affairs. Indeed, by the middle of the 19th century, the country was home to some 350 political journals, including those who regularly printed Daumier’s work, Mitchell said.

However, the politically powerful were especially concerned about lithography’s power to reach the masses. While journals primarily circulated among the intelligentsia, posters were visible everywhere — pasted to poles, hanging in shopfronts and displayed outside cafes.

“You don’t have to be literate to get the message from prints,” Mitchell said. “You could just tack these up in a shop window in view of people passing by. They really were a way for people to learn what was going on.”

She added: “Prints were the internet of the day. They were everywhere.”

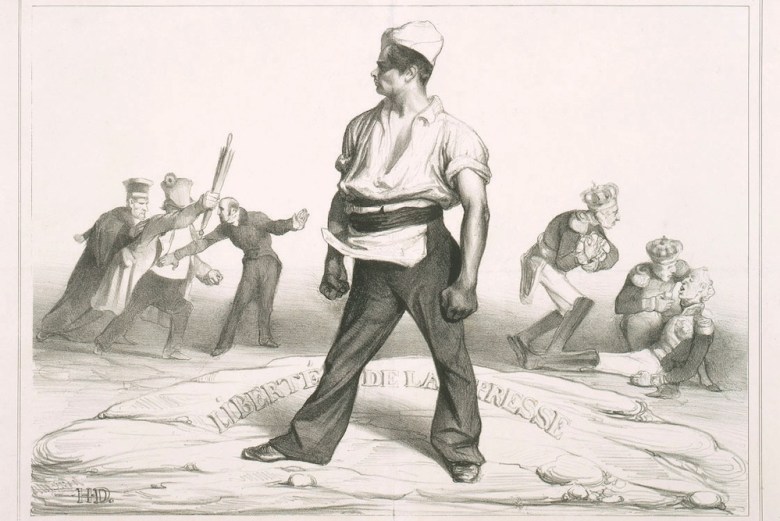

The McNay exhibition also includes more contemporary print works that offer political commentary. Credit: Courtesy Photo / McNay Art Museum

The McNay exhibition also includes more contemporary print works that offer political commentary. Credit: Courtesy Photo / McNay Art Museum

Despite the government’s vigorous attempts to shut down political commentary supplied by artists, their patrons and their printmakers, the creators featured in the exhibition found ways to defy the censors.

For example, the Daumier print from which the show’s name is drawn depicts a printer, sleeves rolled up like a street brawler, his hands stained with ink — or could that be blood? Meanwhile, the background shows fuming censors and a member of royalty either experiencing a fainting spell or out cold from a powerful punch.

Daumier’s far darker Rue Transnonain le April 15, 1834 shows dead civilians sprawled inside a home. Censors approved the print before the addition of its title, which offered viewers a clear indication that it depicted soldiers’ massacre old men, women and children as the government put down an uprising of silk weavers in Lyon.

While some French artists had victories eluding censorship, not all of their works made it through.

Manet’s The Execution of Maximillian shows the death of Emperor Maximilian I of the short-lived Second Mexican Empire. The Mexican soldiers in the firing squad wear uniforms resembling those of the French military, hinting that Manet’s homeland was complicit in the bloodshed.

Censors picked up on the inference and banned the work. The printer was so fearful that Manet would ultimately find a way to replicate the image that he refused to turn over the lithograph stone until after the artist’s death.

Lasting influence

As testament to the power of the French artists, the McNay exhibition also includes works by Pablo Picasso along with famed Mexican artists José Clemente Orozco and José Guadalupe Posada, who were inspired by their predecessors’ unflinching fight to speak truth to power.

Orozco’s 1935 lithograph The Masses draws a clear line back to Daumier’s work, although updating it in a surrealist style. The print satirizes the Mexican elite’s perception of the working class, which is depicted as a lumbering horde comprised of oversized hands and chattering mouths.

“These were the workers whom the state didn’t want to recognize, didn’t want to give rights,” Mitchell said.

In a nod to the lasting power of the political poster art unleashed by Daumier, the exhibition also includes more contemporary lithography that still has the power to provoke.

Donald Moffett’s 1987 lithograph He Kills Me includes a smirking photo of then-President Ronald Reagan. To the left is a brightly colored target the conservative leader had presumably drawn on those affected by the AIDS crisis to which he showed indifference.

The gallery also includes a quartet of posters by the Guerrilla Girls, an anonymous group of female artists devoted to fighting sexism and racism in the art world. The simple, text-driven prints call out the art establishment for its devotion to the works of white males — a group that, ironically, includes Daumier.

Ongoing struggle

The more recent works in “Do Not Meddle With It!!” suggest that while the messages and targets change, artists have struggled with censorship across many time periods and across all regions of the globe.

French history shows that popular uprisings, combined with the ubiquity of the printed image, can throw off the yoke of censorship. However, that same history also shows governments are ready to walk back freedoms.

France’s worst era of censorship ended in 1881, after lawmakers, reacting to public outcry, passed the Press Law of 1881, a more liberal legal framework that dissolved harsh early statutes and remains in effect today.

Even so, government officials subsequently used the turmoil of World Wars I and II to temporarily justify returns to censorship.

“The situation became ungovernable, so they abolished the laws,” Mitchell said of the-1800s popular groundswell. “Until the World Wars came around.”

‘Do Not Meddle With It!!: Print Censorship in 19th Century Paris’

$10-$23, 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Wednesday, 10 a.m.-9 p.m. Thursday, 10 a.m.-6 p.m. Friday, 10 a.m-5 p.m. Saturday noon-5 p.m. Sun through Dec. 7, McNay Art Museum, 6000 N. New Braunfels Ave., (210) 824-5368, mcnayart.org.

Subscribe to SA Current newsletters.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed

Related Stories

California-based Bell pioneered the manipulation of synthetic materials to capture the essence of natural phenomena.

Multi-artist show ‘The Fine ART of Dining’ will be on display through Friday, Aug. 8.

The Saturday show aims to depict the city by its density of spaces where artists live, create and congregate.

This article appears in Sep 3-17, 2025.