When Carmelo Anthony was 16 years old, he and his buddies would pile into a car touring from one Baltimore neighborhood to the next. Any slab of concrete with two competing hoops counted as their battleground. From Patterson Park to The Dome to Boceks, Anthony and company embarrassed any willing challenger at every stop.

D. Watkins, a Baltimore native and the ghost writer of Anthony’s 2021 memoir, knows this because “unfortunately, I was on one of those teams that got the [crap] beat out of us.”

It was on those playgrounds where word spread about the kid from West Baltimore’s Murphy Homes, lauded as the city’s next big thing. Anthony’s trajectory came to fruition by virtue of his one-and-done championship season at Syracuse and a 19-year NBA career, having retired as one of the game’s preeminent scorers. Team Melo program director Sam Brand deemed Anthony “the gold standard for Baltimore basketball success.”

A quarter-century removed from taking lunch money on the playgrounds, Anthony will see his name enshrined into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame. The ceremony is scheduled for Saturday evening in Springfield, Massachusetts.

Basketball introduced Anthony to a world beyond the four blocks he called home.

As a high school senior, he transferred from now-defunct Towson Catholic to powerhouse Oak Hill Academy in Virginia. College ball pulled him to upstate New York. Anthony played for six NBA teams, spanning the country from New York to Los Angeles. He won three Olympic gold medals in Beijing, London and Rio de Janeiro.

And yet, he is dedicating a life after basketball to leaving his fingerprints on the city that raised him.

Watkins said Anthony likes to keep a low profile on all the investments and resources he gives back to Baltimore. He doesn’t need to be the face of change as long as he can make an impact. Anthony’s latest venture is hard to hide from: a free exhibition bearing his name at the Enoch Pratt Library’s Central location. “House of Melo” opens on Oct. 25 and runs through late December. Modeled after Brooklyn Public Library’s “Book of HOV,” a Jay-Z tribute, Pratt will showcase the life and career of a Baltimore hoops legend.

“A lot of times, people who achieve success from those place are bitter and jaded about the things that went down when they didn’t have anything that they want to stay as far away as possible,” Watkins said. “When Carmelo’s in Baltimore, he’s not hobnobbing. He’s around the people he came up with.”

In a 2021 interview with The Baltimore Sun, Anthony spoke candidly about his formative years in Baltimore and the staying power those experiences have had on his adult life.

“That’s my makeup. I mean, that’s who I am,” Anthony said at the time. “And a little bit can be survivor’s remorse. You know, not wanting to feel like I’m too far away from those people I grew up with.”

With “House of Melo,” Anthony’s story draws a blueprint for a younger generation. One that isn’t exclusive to supreme athletic talent.

The brick-and-mortar exhibit designed by Watkins, the imminent Hall of Famer and his longtime personal stylist, Khalilah Beavers, wraps up by the end of the calendar year, but the library is planning to host free workshops over the next 12 months, geared toward those with NBA aspirations, lacking the basketball chops. They’ll host sports agents, writers and sneaker designers to impart wisdom on the city’s youth.

“Like the Pratt, [Anthony’s] story shows the power of making history, culture and opportunity open to everyone,” said the library’s CEO Chad Helton.

In many ways, his story is a product of the Baltimore legends before him. It motivated him to be the next great torch-bearer for Baltimore hoops.

Sam Cassell, a three-time NBA champion and current assistant coach for the Boston Celtics, was a sounding board as Anthony rose through the basketball ranks. Fellow Dunbar legend Michael Lloyd, known colloquially as “Real Deal,” played at Syracuse, but when his own career flamed out, Lloyd returned to Baltimore to help Anthony. “Surprise, Carmelo ends up going to Syracuse and wearing No. 15, the number that Mike wore,” Watkins said. Mark Karcher was from that same generation. The St. Frances legend bullied Anthony the first time they played. Anthony compartmentalized that lesson, came back, and, as Watkins put it, “tore Mark apart.”

The way those neighborhood heroes poured their time and energy into a young Anthony is the same way he pays it forward, be it through his AAU program Team Melo or mentorship for those following in his footsteps.

Kenneth K. Lam / Baltimore Sun

Carmelo Anthony pays a surprise visit to kids at the Carmelo Anthony Youth Development Center in Baltimore. Tyion Taylor, 6, left, a first-grader at Inner Harbor East Academy, shakes hands with Anthony after giving him a strawberry cheesecake. (Kenneth K. Lam/Staff)

When a high-school-aged Derik Queen, now a rookie with the New Orleans Pelicans, was in Manhattan for a workout, he stayed at Anthony’s apartment and chirped the Hall of Famer with the gall of a kid “from Baltimore.” When Bub Carrington, a rising sophomore with the Wizards, was making waves as a high schooler at St. Frances, Anthony was there for him, too. Carrington’s late father, Carlton Carrington Jr., refined Anthony’s triple-threat scoring bag. So Anthony made sure “Lil’ Bub” had the same tool kit at his disposal — now a cornerstone of Carrington’s nascent NBA career.

“What I love about Melo, he just loves to see the next up,” Brand told The Sun this summer. “He loves when they’re from here.”

Some folks waffle on the merit of Anthony’s Baltimore roots. He was born in Red Hook, Brooklyn, and moved to Baltimore at 8 years old. Despite the “West Baltimore” tattoo on his shoulder, New York reclaimed him through seven illustrious seasons with the Knicks.

In 2012, shortly after Anthony had arrived to save the Knicks from mediocrity, Watkins was in New York to see Mike Tyson’s one-man show. He ran into Spike Lee, director of the show and the poster face of Knicks fandom. Lee didn’t pick up on the Baltimore accents when he started talking to Watkins about “the Brooklyn boy coming back to New York to save New York.”

Watkins cocked his head, “Well, who’s that?”

“The Melo man!” Lee exclaimed.

“He from West Baltimore,” Watkins said, smoothly, “Stop it.”

Lee swatted the air and walked off. He returned minutes later. Watkins was busy buried in his phone and didn’t notice. He jolted up when Lee blurted out in his direction, “He was born in Brooklyn!” Watkins cracked up retelling the story.

“Carmelo fell in love with basketball and he made a name for himself while living here,” Watkins said. “He loves the city and he had a unique experience that a lot of us don’t have.”

It has influenced a lifetime of giving back.

Have a news tip? Contact Sam Cohn at scohn@baltsun.com, 410-332-6200 and x.com/samdcohn.

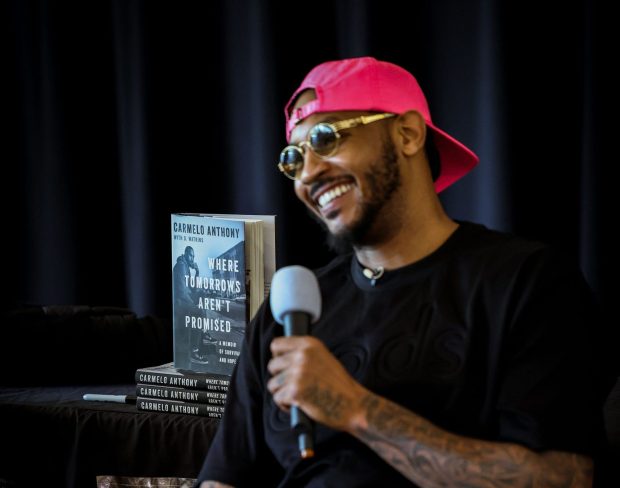

Carmelo Anthony discussed his memoir “Where Tomorrows Aren’t Promised” during a book signing at The Garage at R House in Baltimore in 2022. (Steve Jenkins)

Carmelo Anthony discussed his memoir “Where Tomorrows Aren’t Promised” during a book signing at The Garage at R House in Baltimore in 2022. (Steve Jenkins)