This column originally appeared in On The Way, a weekly newsletter covering everything you need to know about NYC-area transportation.

Sign up to get the full version, which includes answers to reader questions, trivia, service changes and more, in your inbox every Thursday.

While most commuters bury themselves in books, catch up on emails or zone out with noise-cancelling headphones, a rare breed of straphanger studies how people use the transit system and interact with each other.

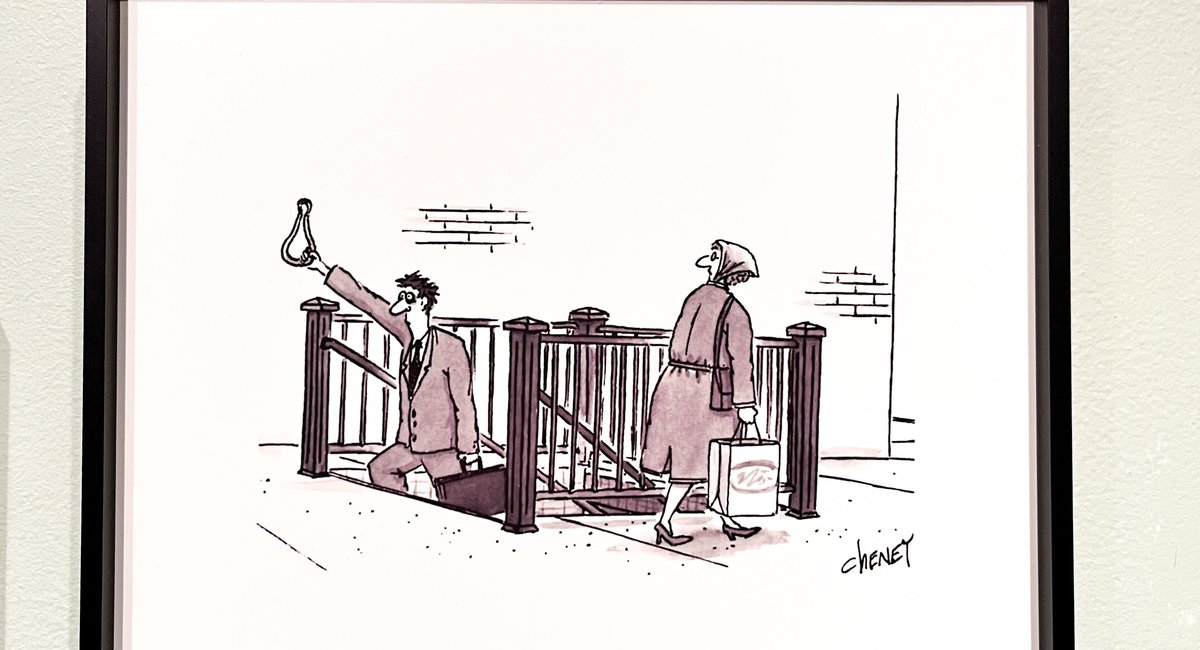

Those would be the New Yorker’s exalted cartoonists, who are celebrated in a new exhibit showcasing 100 years of cartoons about the subway.

The show makes clear that subway etiquette has been fodder for the magazine since it was first published in 1925.

Jodi Shapiro, the curator of the New York Transit Museum, reviewed 500 New Yorker cartoons spoofing people talking loudly on the trains, manspreading and sneaking a peek at what others are reading.

“ Everyone thinks it’s kind of a new thing, but it’s been around since time immemorial,” Shapiro said.

The exhibit, “A Century of The New Yorker’s Transportation Cartoons,” is open at the Transit Museum’s annex at Grand Central Terminal until October.

One cartoon from 2019 by artist Ellis Rosen shows two cowboys — one standing on the platform and one in the doorway of an A train — in an Old West-style standoff. “You ain’t gittin’ on this train until I git off first,” the caption reads.

“ In my family this was a very important subway etiquette rule that should be enforced, in my opinion,” Rosen said. “ Normally you’re making fun of etiquette, but in this case, I take this very seriously. So, I couldn’t make fun of it, I just had to make fun of the offenders of that particular rule.”

Not unlike a reporter who rides the subway looking for potential stories, Rosen said he rides looking for characters, humor and breaches of etiquette.

“ I just stare at people. It’s not good. I gotta stop, but you just can’t help it,” he said. “People come on, people come off and then you start thinking, ‘What are they doing? What are they up to?’ And then you try to remind yourself, ‘I wonder if there’s a cartoon in any of this?'”

“And sometimes you get lucky in the subway,” he added. “You get lucky more often than anywhere else in my experience.”

Rosen said he tries to avoid falling into the trap — familiar to reporters as well — of only portraying the worst of the subway system.

“Sometimes I worry that I’m looking out for bad etiquette, just so I can be righteously mad at them,” he said.

But Shapiro chimed in to note that’s part of the experience.

“ That’s a very New York thing. Just like waiting to get mad at something,” she said.

But even more than that, the subway cartoons depict what it’s like sharing a space that is often cramped, dirty and unpleasant but also somewhere people have to be. That sentiment is captured in the very first subway comic in the New Yorker from 1925. A man wipes grime off a subway car window next to a sign that reads, “Please! Help Us Keep The ‘L’ and Subway Clean.”

It isn’t clear if he’s following the advice, or just clearing off the gunk so he can see which stop he’s at.

“It kind of captures what it’s like to live here, without actually explaining to people what it’s like to live here,” Shapiro said.

Beer and oysters. Tracks Raw Bar & Grill, a longtime Penn Station favorite, finally opened in Grand Central Madison this week, becoming the first major retail operator in the 150-foot-deep subterranean station.

Most of the retail and restaurant spaces in the new terminal — which finally opened in 2023 after more than a decade of delays — have remained empty while the MTA struggles to secure tenants.

A statistically horrible stretch for the subways. The MTA reported 138 major incidents — or calamities that delay 50 or more trains — in June and July, the highest for those two months since 2018, when the city’s transit system was under a state of emergency.

The buses aren’t great either. More than half of New York City buses got failing grades in a new analysis that crunched MTA data on speeds, on-time performance and frequency of delays.

Audio art. “If you hear something, free something,” a new work by conceptual artist Chloë Bass, is taking over the public address systems in 14 subway stations citywide through Oct. 5.

Ghost cars misbehaving. It turns out that drivers of cars with illegal out-of-state license plates or no plates at all are more likely to have outstanding tolls and fines, speed in school zones and block fire hydrants, according to a new City Council report.

Student OMNY cards. Students who live more than a half-mile from their school are getting nifty green OMNY cards that offer four free rides every day, seven days a week.

Listen to us talk about all this! Download our app and tune in to “All Things Considered” at 4:50 p.m. Thursdays.

Curious Commuter

Have a question for us? Use this form to submit yours and we may answer it in a future newsletter!

Curious Commuter questions are exclusive for On The Way newsletter subscribers. Sign up for free here.

Question from Barbara in Manhattan Officials are still touting the success of congestion pricing, but it seems to me that the bad old days are coming back a little. Are there any recent stats or are they still using the early numbers?

Answer

If by the “bad old days” you’re referring to Manhattan’s heavy congestion before the tolling program went live in January, it might be because of how busy the city gets during peak summer tourist season in June and July.

By the latest metrics, the congestion pricing program is still achieving its goal. June and July data shows that vehicles traveling into the Central Business District — Manhattan below 60th Street — are down 12% compared to the same two months last year. That’s around 62,000 fewer cars on the road.

Average daily subway ridership for June, July and August was higher this summer than the summer of 2024, before the tolling program began. There’s also summer holidays to take into account, when New Yorkers with cars drive out of town. That means heavier congestion in the tunnels and on bridges leaving Manhattan.