Blanca Lucio likes to spend her mornings tending to her zucchinis, cucumbers, watermelons and traditional Mexican herbs at a small community garden near downtown Los Angeles. With its cool, damp air, the garden brims with what Lucio calls “magic.”

The only sound comes from green June bugs buzzing by her ears and children playing at the community center across the street.

“Outside of here, you’re exposed to a lot of noise and a lot of pollution,” Lucio said while giving a tour of the garden, a short distance from her home in South-Central L.A. “This space renews me and the other gardeners who grow plants here. I feel more content when I’m here.”

Noise pollution and excessive heat can seem inescapable in L.A. What would the city be without random bursts of fireworks and car sound systems thumping loud enough to shake you from your dreams? And the nearly 365-days-a-year sunshine is practically what defines L.A. sunshine, even though it means commuters often must wait under the blazing sun at bus stops that lack cover.

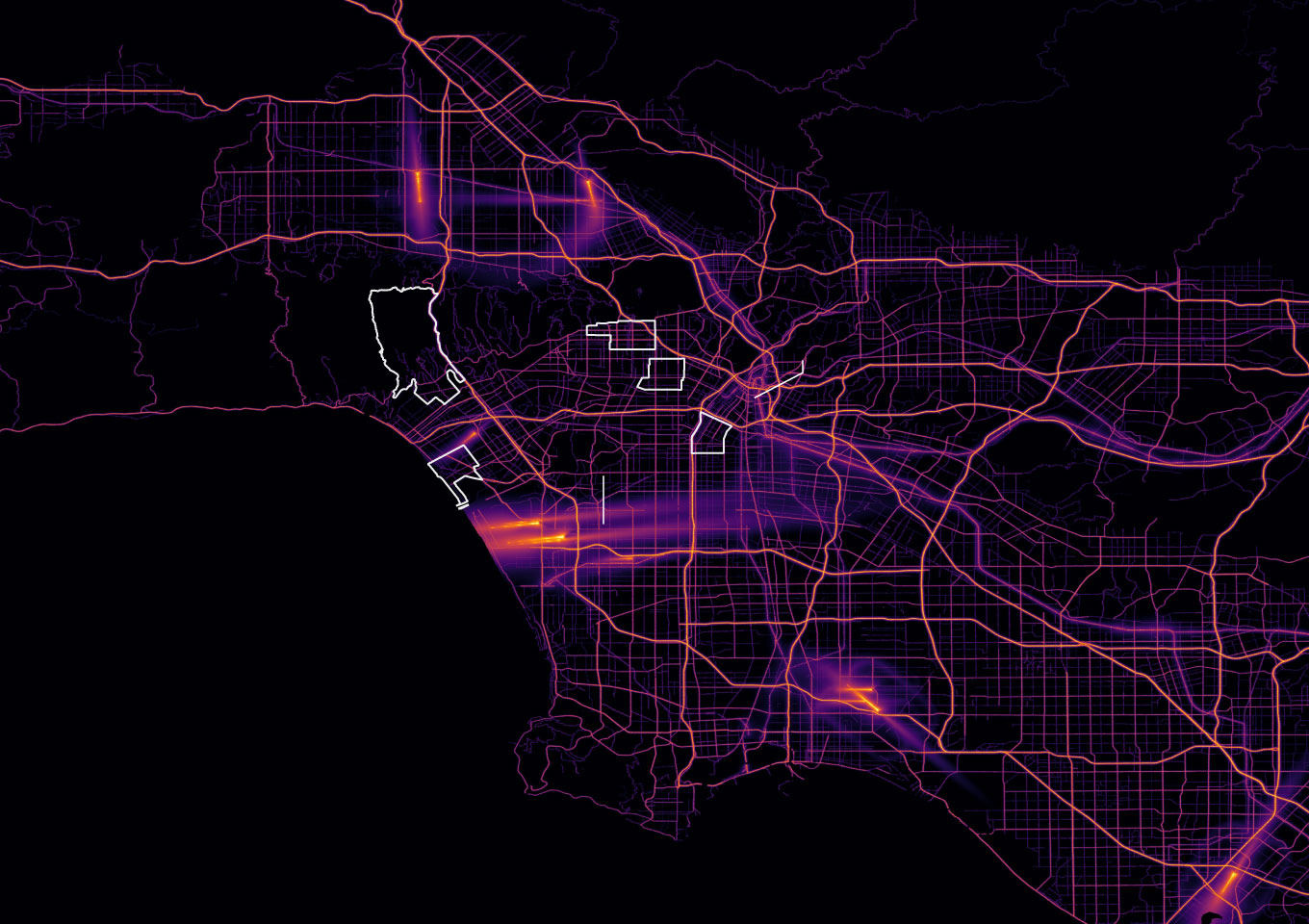

Busy roads and airports are a large contributor of noise pollution in Los Angeles

U.S. Department of Transportation

Sean Greene LOS ANGELES TIMES

But just because we’ve grown used to L.A.’s jarring soundscape, shadeless streets and pockets of intense heat, it doesn’t mean they are harmless.

Noise and heat together can pose a special kind of health threat, one that the city’s most vulnerable people are least able to protect against, said Valerie Tornini, a neurobiologist at UCLA.

With climate change ushering in stronger and longer heat waves, a growing body of evidence suggests that excessive heat has become a public health crisis. An estimated 1,300 people die of extreme heat each year, according to the Environmental Protection Agency, and that number will only grow in coming years.

Both heat and noise can harm the nervous system, interfere with metabolism and disrupt sleep patterns. They can also aggravate conditions such as diabetes, hypertension and cardiovascular disease, according to a paper published in Environmental Health Perspectives.

Tornini leads a team of brain researchers trying to figure out how the combination of these two environmental dangers affects brain health and behavior among residents of Central and South L.A.

Her team is working with the Boston-based nonprofit Prospera Institute and the South L.A. social justice nonprofit Esperanza Community Housing Corp. to collect stories from local Latino and Black Americans, like Lucio, about how they cope.

The collaboration started in 2024 after Tornini, who had been studying the effect of noise and heat on neural development in zebrafish, reached out to Joanne Suarez, who founded Prospera to promote health equity in Black, Latino and Indigenous communities.

Their partnership sprang from a recognition that brain science has lagged behind other disciplines in recognizing the need for community-centered research that treats study participants as equal partners, Tornini said.

The project revolves around two interwoven prompts, she said: “How can it do good and no harm, and how can it serve the cause of justice?”

Joanne Suarez speaks with South L.A. community members about how they’re affected by excessive heat and noise during a focus group at Esperanza Community Housing.

(Carlin Stiehl / Los Angeles Times)

“Sometimes [research] is not aligned with what the community wants and needs,” Tornini said. “I want to listen: What are your concerns? What are your lived experiences? People’s stories and oral histories … can influence the kind of questions that we ask in the lab, and then that data goes back to them.”

That shift in thinking was in evidence on a Saturday morning in July at Mercado La Paloma — a South L.A. food hall that houses the Michelin-starred Mexican seafood restaurant Holbox as well as Esperanza Community Housing’s offices.

A dozen women sat in a circle with Suarez and Tornini for an intimate listening session, held in Spanish, about living with noise and heat.

Suarez invited the women to speak in response to a series of questions printed on a handout. For example: “How do environmental factors like noise and heat impact your health and daily life?” and “Have you noticed changes in your ability to focus, think clearly or even remember things when it’s extremely hot or noisy in your community?”

One woman said it’s hard to mitigate one disturbance without exacerbating the other, such as when she opens the window of her bedroom at night to let in fresh air, only to be kept awake by noise from passing planes and sirens. A mother worried about the effect of sun and heat on her kids during gym class and recess at school. One woman told the group that excessive heat worsens her hypertension headaches, while another said that when it’s hot out, she gets more irritated by noises she can’t control.

Another participant said she fears getting caught in the crossfire of warring gangs in her neighborhood and so won’t sit outside to get fresh air, no matter how hot it gets indoors.

The UCLA initiative is as much an experiment in trust-building as data collection, said Monic Uriarte, a public health advocate and community organizer at Esperanza Community Housing who has lived and worked in L.A.’s urban core for three decades.

Wariness of scientists and healthcare professionals — born of a history of one-sided research that never benefited study volunteers or their communities; nonconsensual lab experiments; and racial discrimination among medical practitioners — is commonplace in some communities of color.

“I love higher education, but we are tired of being guinea pigs for different studies,” Uriarte said. “We need this kind of collaboration — a space for our community to share, in our own words, the experience of living in South Los Angeles.”

She’s excited about the prospect of volunteers being able to cite whatever findings result from the research when asking city officials for noise mitigation for their homes, tree plantings or more open spaces.

Living and commuting in L.A. means navigating an environment that can make you want to cover your ears and run for the shadows.

The relentless flow of vehicles and Metro light-rail trains drowned out Blanca Lucio’s voice as she gave a tour of South-Central L.A., walking past auto-body shops and restaurants at the intersection of San Pedro Street and Washington Boulevard.

Not far away in the downtown jewelry district, sidewalk vendors selling wares as varied as avocados, roasted corn, cellphone cases and brass lanterns shielded themselves from the intense midday sun with beach umbrellas, or by clustering in the shadows of high-rises.

During L.A.’s recent heat wave, when temperatures regularly surpassed 90 degrees, a woman selling rose bouquets out of buckets at Pershing Square looked beleaguered while standing in the paltry shade of a tree. A man pushing a cooler full of 50-cent bottled waters wiped sweat from his forehead and tried to cool down with a Spanish fan.

A woman sleeps on a bench in Los Angeles’ Pershing Square in June 2024.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

There was no escape from the onslaught of car horns, rumbling motors and pedestrians blasting music from speakers stuffed in backpacks.

About 10 miles south is the Harbor Freeway transit terminal, an important hub for commuters who need to catch a bus or train in South L.A.

The terminal is located on a raised platform in the middle of a concrete tangle of ramps and the elevated lanes of the 105 Freeway. The commotion and noise are unnerving; cars speed by so close you can feel whooshes as they pass.

But even if you don’t have to wait daily for transport while being inundated with the sounds of a Los Angeles freeway, you may be forced to endure some noise pollution seemingly designed to disturb the peace. On any given evening in the city, drivers and bikers amp up the soundscape by revving their engines while waiting at traffic stops, then slam on the gas when their light turns green, screeching down the street.

Nighttime also brings the piercing sound of street takeovers. Drivers draw crowds of spectators as they perform stunts such as “doughnuts” — spinning their cars in circles until their tires burn rubber marks on the pavement. The phenomenon has become such a problem countywide — with shootings and cars set on fire at some of them — that officials have vowed to crack down on the illegal gatherings.

L.A. is notoriously noisy and hot, but experiences like these are widespread across the U.S.

About 95 million Americans, nearly one-third of the U.S. population, are subjected to transportation-related noise pollution, with Latino, Black and Asian communities disproportionately exposed to it, according to data compiled by researchers at the University of Washington.

Noise is measured in decibels, with a middle range of 50-60 considered a normal level of ambient sound that doesn’t pose a risk to health. Most people experience noise at this level while doing routine things such as working at an office or walking down a street with little to no traffic. Emergency sirens, lawn mowers and music in a nightclub, by contrast, can exceed 90 decibels.

While grating noises and intolerable heat may be experienced in pockets across the city, making it hard to draw direct comparisons, some whole sections of L.A. feel conspicuously beset by these environmental disturbances. Other neighborhoods feel more insulated.

A pedestrian crosses a median as traffic passes along San Vicente Boulevard in Brentwood.

(Genaro Molina / Los Angeles Times)

The urban core and South L.A. — where the median household income ranges from $48,000 to $62,000 a year and Latino and Black people make up the majority of the population, according to the U.S. census — is a wall of sound and a bubble of heat. But farther west in predominantly white Brentwood, where the median annual household income is more than $160,000, walls of semi-tropical foliage insulate many private homes from intrusive noises and overhanging trees form of canopies of coolness over gently curving streets.

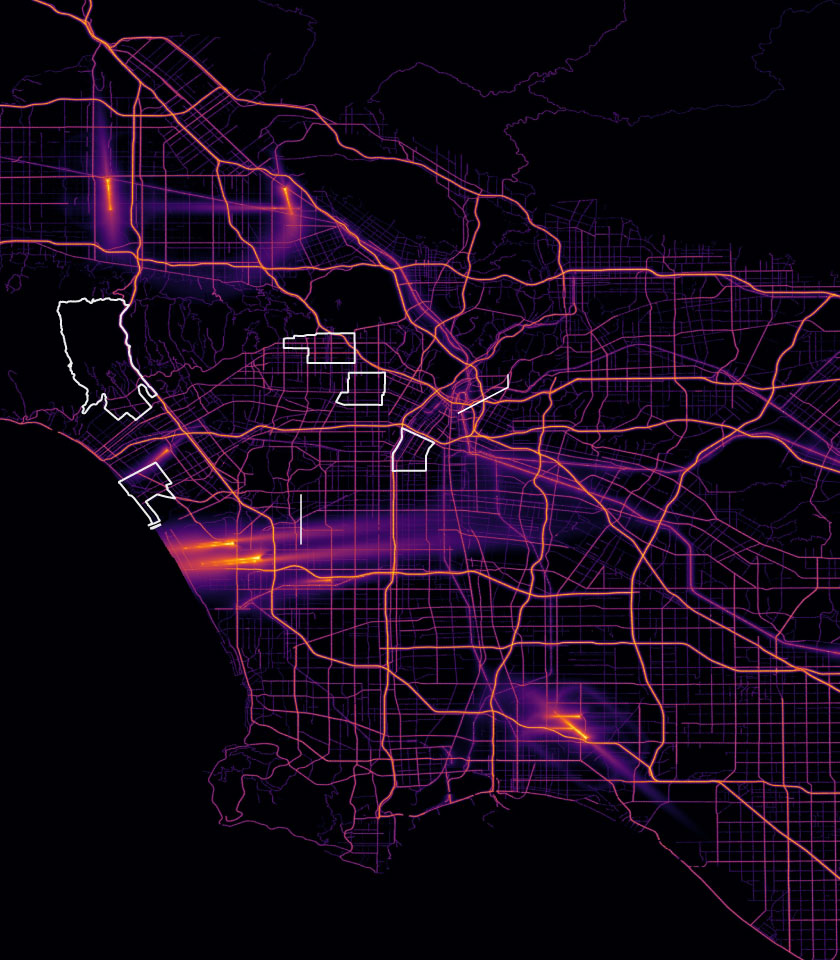

A treeless city

U.S. Geological Survey, U.S. Census Bureau

Sean Greene LOS ANGELES TIMES

Take a sunset walk along the gently sloped, flower-scented streets above busy Sunset Boulevard in Brentwood — you will be immersed in a stillness broken only by birds chirping in the treetops. To the south, along the historic canals of Venice, ocean breezes cool the air and the prevailing sound is of fountains trickling in homeowners’ yards.

By contrast, noises associated with law enforcement are such familiar nuisances on the relatively bare streets of South L.A. that they are treated as if they are part of the natural environment. The late artist 2Pac rapped about the menacing presence of “ghetto bird” police helicopters in 1996‘s “To Live and Die in L.A.,” and Compton-born rapper Kendrick Lamar referenced ghetto birds and samples the piercing wail of police sirens on “XXX,” released in 2017.

“Basically, the Blacker the neighborhood, the more flight hours; the more Latinx the neighborhood, the more flight hours … and the Blacker the neighborhood, the lower the helicopters are flying,” said Nick Shapiro, a multidisciplinary environmental researcher at UCLA.

Shapiro has spent years using L.A. Police Department flight data to map helicopter trajectories across the city in studies of “sonic inequality” that his team conducted jointly with residents of South L.A.

Helicopter noise is an issue citywide — even in typically serene, higher-income neighborhoods. The noise is a problem for outdoor TV and film productions too, Shapiro said.

Still, Shapiro said, “there’s pretty extreme inequality between Malibu and Watts.”

Meanwhile, it’s even worse for those in South L.A. who live in the L.A. International Airport flight path and have to contend with both helicopters and the earsplitting sonic reality of jets landing and taking off.

West Century Boulevard runs along the airport’s flight path, meaning that every couple of minutes, a low-flying jet cuts a trail of the high-frequency whines and low-frequency roars on its approach to the airport, sending decibel levels into the 90s. Because of all the broad, shadeless streets that define many of South L.A.’s neighborhoods, the hot summer sun seems to bear down more intensely on these communities of color too.

Plane spotters get a close-up view of planes on their final approach to Los Angeles International Airport.

(Gina Ferazzi / Los Angeles Times)

One sunny afternoon in August, Charles Lewis, a retired store clerk, sat in a folding chair under a solitary shade tree and watched a steady stream of cars and trucks rush past him on Century. As one plane after another shrieked across the cloudless sky, jet-shaped shadows raced across the pavement, alongside cars.

Lewis lives close by but lamented that sidewalks along residential streets closer to his home are too exposed to the sun. He’s witnessed shade gradually disappear in the 40 years he has lived in the neighborhood and believes law enforcement agencies are partly to blame.

Los Angeles Police Department Deputy Chief Donald Graham acknowledged that his agency has asked city crews to trim publicly maintained trees to improve street lighting and deter illegal activity in specific trouble spots.

“We’re always trying to balance the beautification of the city and the need to have a tree canopy with public safety,” he said.

The cacophony of the boulevard offers little in the way of tranquility, but Lewis said the noise from jets is so bad at home that he has to turn up the volume on his TV and wait for aircraft to pass to have a conversation without yelling.

At least his perch on Century provides a refuge from the excessive heat.

“This is the only shade I have,” Lewis said.

Nearby, the late-day sun felt oppressive along a busy, tree-less stretch of Slauson Avenue near the 110 Freeway. Two women at a food stand squinted in the sunlight as they cooked whole chickens on a hot grill to serve with freshly made tortillas and beans and rice.

A metro train traveling on the K Line passes a mural of the late rapper Nipsey Hussle that is located on Crenshaw Boulevard at Slauson Avenue in Los Angeles.

(Mel Melcon / Los Angeles Times)

Too busy filling orders to talk, the women laughed and said they’ve given up trying to stay cool while working on days like this.

Meanwhile, six miles north, things weren’t much better. At the junction of Olympic Boulevard and Western Avenue in Koreatown, a search for both shade and quiet was an exercise in futility. The sparse landscaping on the thoroughfares left sidewalks exposed to the bright sun, and the constant rumble of trucks and buses assaulted the eardrums.

A mile away, in the flats of Hollywood near Paramount Studios, the block letters of the district’s famous hilltop sign appeared like a vision through the smoggy air above a bustling intersection at Melrose Avenue and Vine Street — though on a recent August day, the 85-degree temperatures, blazing sunlight and din of speeding vehicles made it that much more difficult to savor the view.

Traditional lab-based brain research has too often discounted the health challenges that come with navigating an ecosystem as complex and inequitable as L.A.’s, said Helena Hansen, professor and interim chair of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at UCLA’s Geffen School of Medicine.

The noise and heat study, along with the analysis of helicopter noise, are part of a broader effort to incorporate information about social and physical conditions into research design, she said.

“We’re really trying to rethink the way science is done,” she said.

At the listening session in July, the idea of breaking down the barrier between laboratory science and real life was on full display. Nearly all the women nodded in agreement when one brought up her struggle to focus on tasks or relax because of heat and noise. It was clear that for these Angelenos, stress is the norm — peace the exception.

Lucio was among those who attended. She is participating in the UCLA study not just to help the researchers, she said, but also to make living in L.A. more comfortable and healthier for herself and her neighbors.

The surrounding neighborhood, just across a busy freeway from the University of Southern California’s campus, is one of several in Central L.A. that the budding citizen scientist has surveyed as part of her own study of the area’s spotty tree canopy.

“We need more trees,” Lucio said. “I’ve noticed people walking around searching for shade and clustering in the few spots where they can find it…. I’ve even seen dogs searching for shade in this neighborhood.”

Trees provide a canopy for travelers along Grayburn Avenue in Los Angeles’ Leimert Park neighborhood.

(Brian van der Brug / Los Angeles Times)

It’s little slices of life and firsthand observations such as these that the UCLA scientists and Prospera facilitator want to heed as they pursue their research. The group just secured additional funding for further study and possibly to record accounts of lived experiences on video, Suarez said. For now, Tornini, the brain scientist, just wants to keep the line of communication open with participants.

“The goal is for this to be a living relationship that is shaped mutually,” Tornini said. “What the community does with this information is within their own power. And if they ask — how can we help?”