Executive Summary

About 10 years ago, New York State embarked on a plan to “transform” its mental health system. This plan entailed shifting resources from state-run inpatient to community-based programs. When the shift began, the state’s system of psychiatric centers had already lost over 90 percent of the beds that it had at its peak, decades earlier. Nonetheless, then-Governor Andrew Cuomo argued that New York was burdened by hundreds of “unnecessary” beds that should be cut, which would lead to superior care at a cheaper cost.

As the state Office of Mental Health (OMH) implemented this plan throughout the 2010s, pressures built on systems outside the mental health system proper and run by New York City— most notably, criminal justice and homeless services. That result raised questions as to whether costs were being shifted from the state to the city and the effectiveness of community-based care.

The Transformation Plan remains official state policy. However, after taking office in August 2021, Governor Kathy Hochul has made modifications, including adding beds to the state psychiatric center system and loosening civil commitment standards.

This report, an update of a 2018 report,[1] assesses what 10 years of “Transformation” has meant for New York’s seriously mentally ill. It examines the effects that changes in state psychiatric hospital bed supply have had on city-run public systems, such as jails, homeless services, and city hospitals. The 2018 report examined those effects at a time when bed counts were declining. This update assesses the effects at a time when bed counts have been increasing.

The chief findings include:

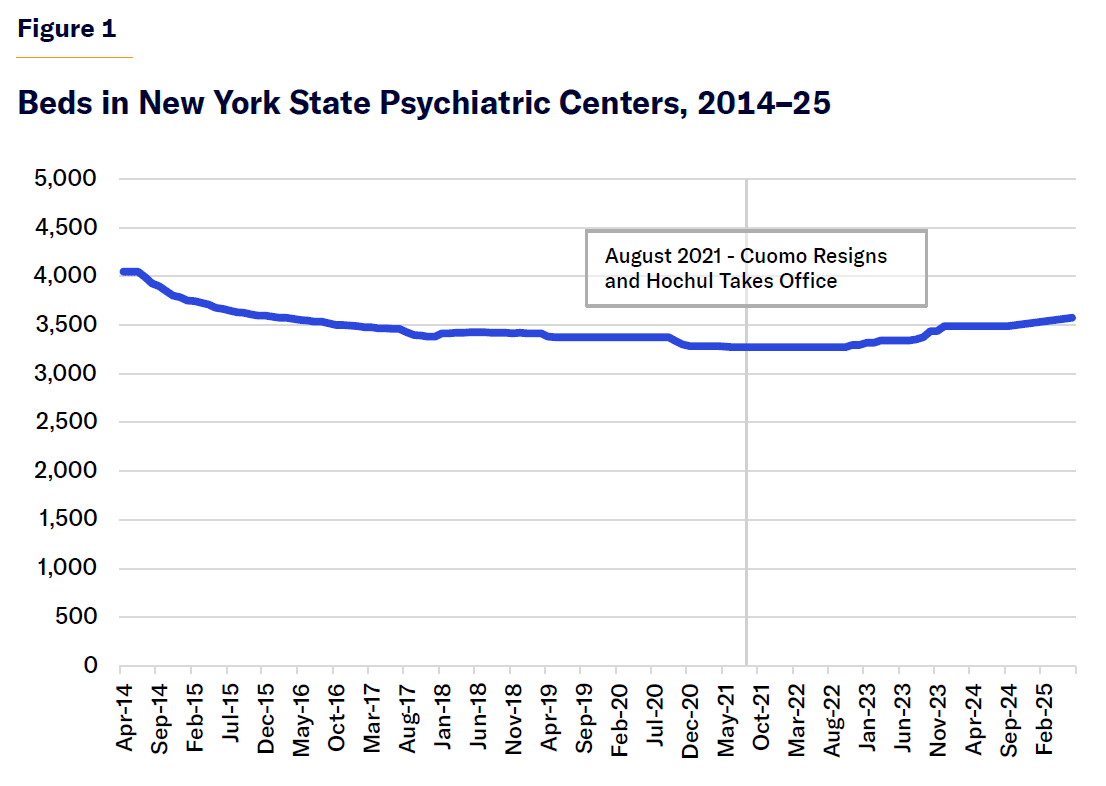

- Between the beginning of the Transformation Plan in 2014 and Cuomo’s resignation in 2021, New York lost more than 700 state psychiatric hospital beds. Since Hochul took office, the state has gained back about 300 beds. Though modest in scope, the Hochul investments are nonetheless historic. The first net gains in decades, Hochul’s bed increases signal that deinstitutionalization is over in New York State. There are currently about 3,600 beds in state psychiatric centers, statewide.

- Despite recent changes in reimbursement policy, New York State and City both have lost about 10 percent of the psychiatric beds in general hospitals that they had in 2014.

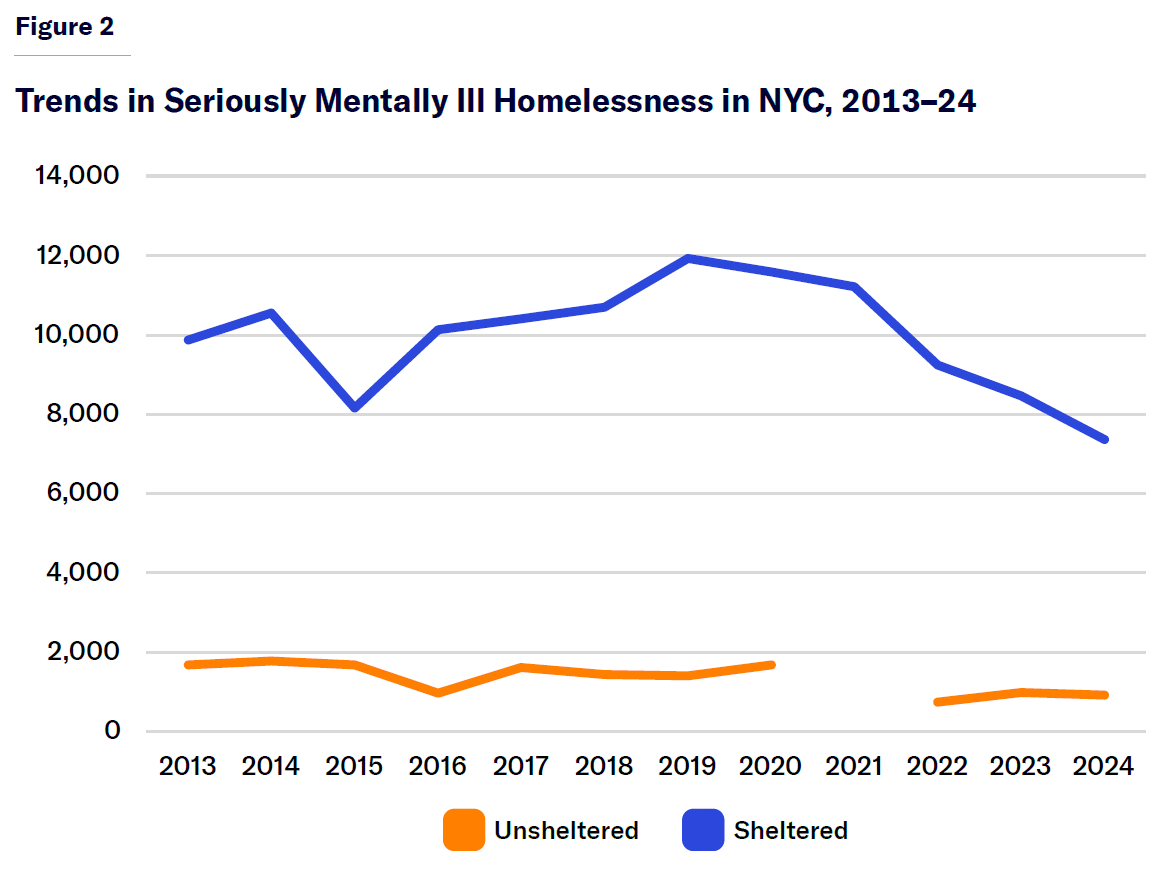

- The number of seriously mentally ill homeless who are temporarily in a shelter (sheltered homeless) hit a peak shortly before Covid, and has since declined.

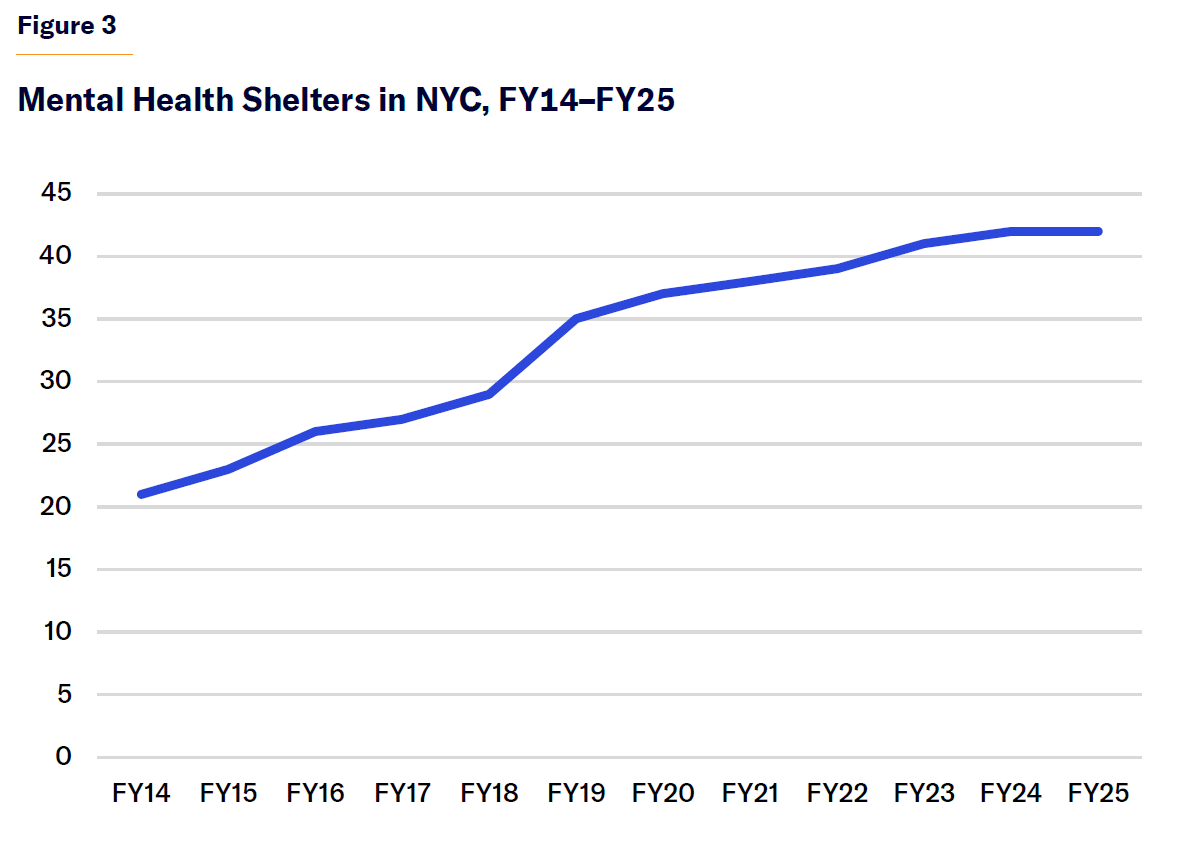

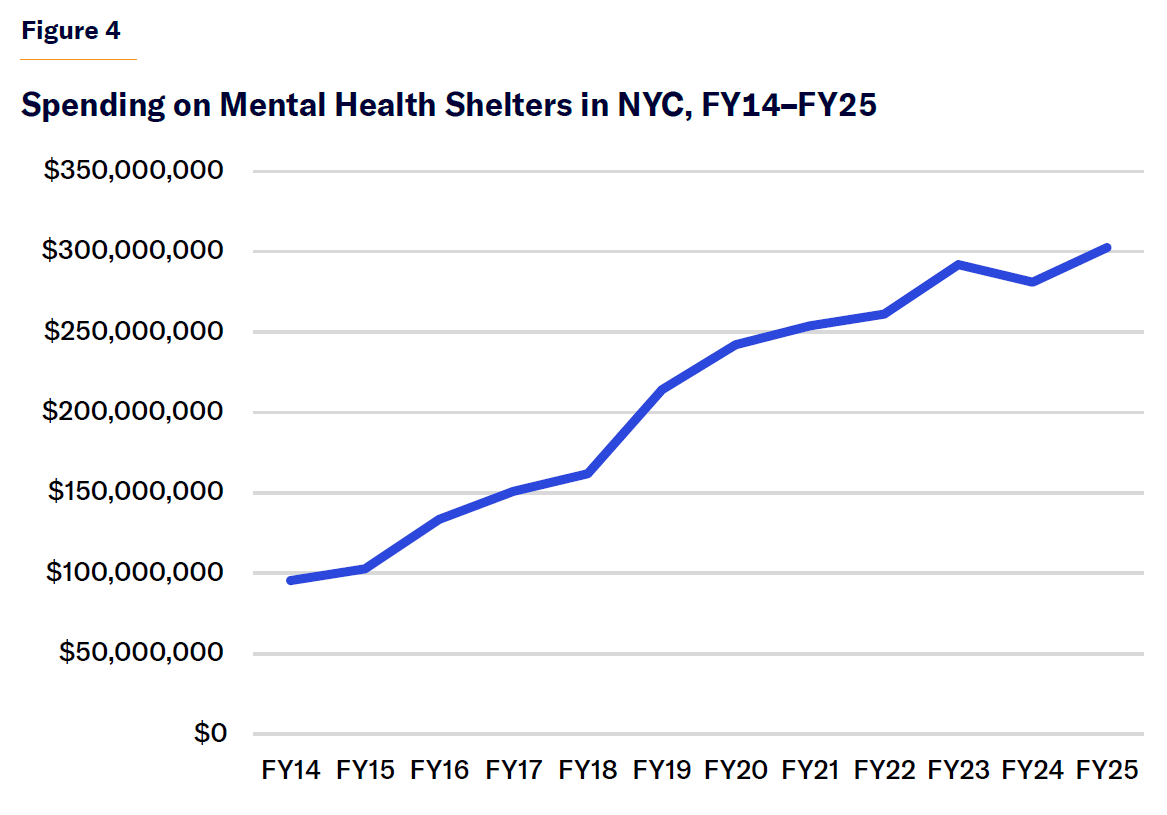

- The number of specialized mental health shelters in NYC rose from 21 to 42 between 2014 and 2025. Mental health shelters are home to a larger population of seriously mentally ill individuals than jails and psychiatric hospitals. Mental health shelters cost NYC $300 million annually. The rate of growth of mental health shelters and spending on them has slowed in recent years.

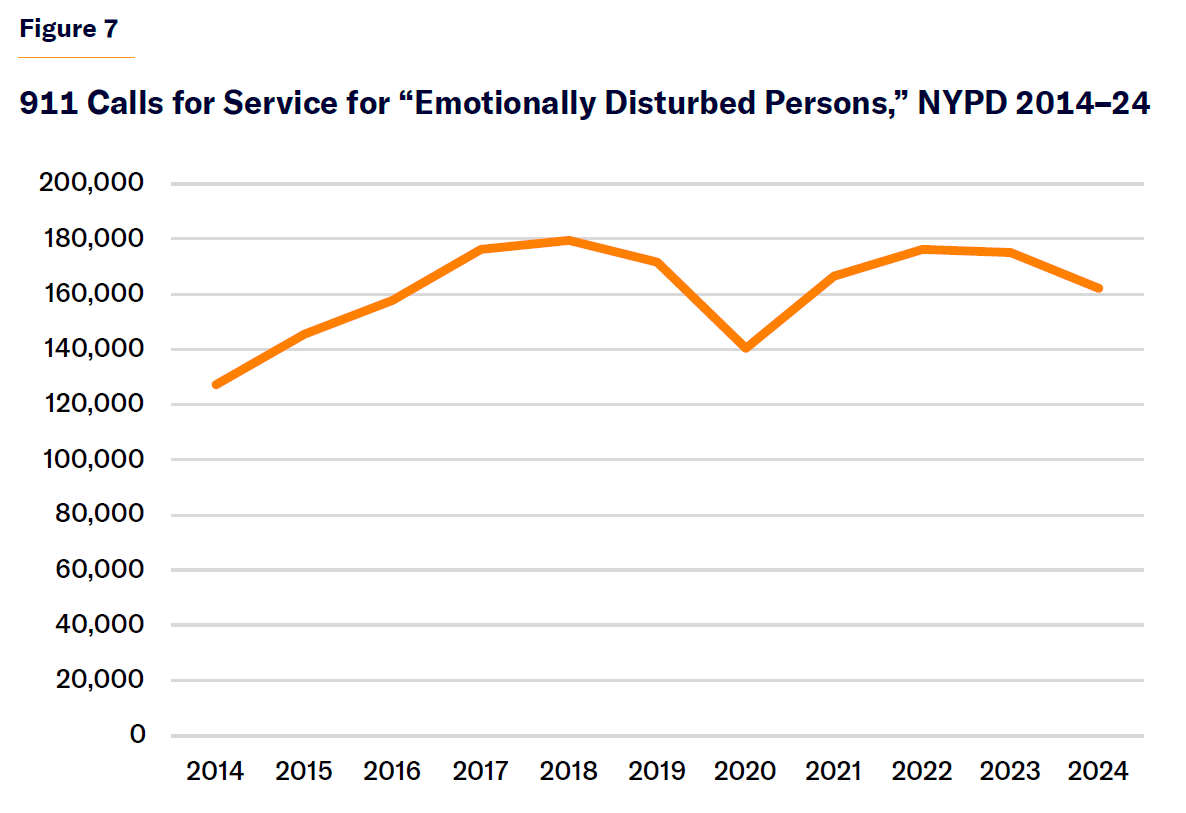

- The New York Police Department fields more “emotionally disturbed person” calls than in 2014, but the number has been stable since the late 2010s.

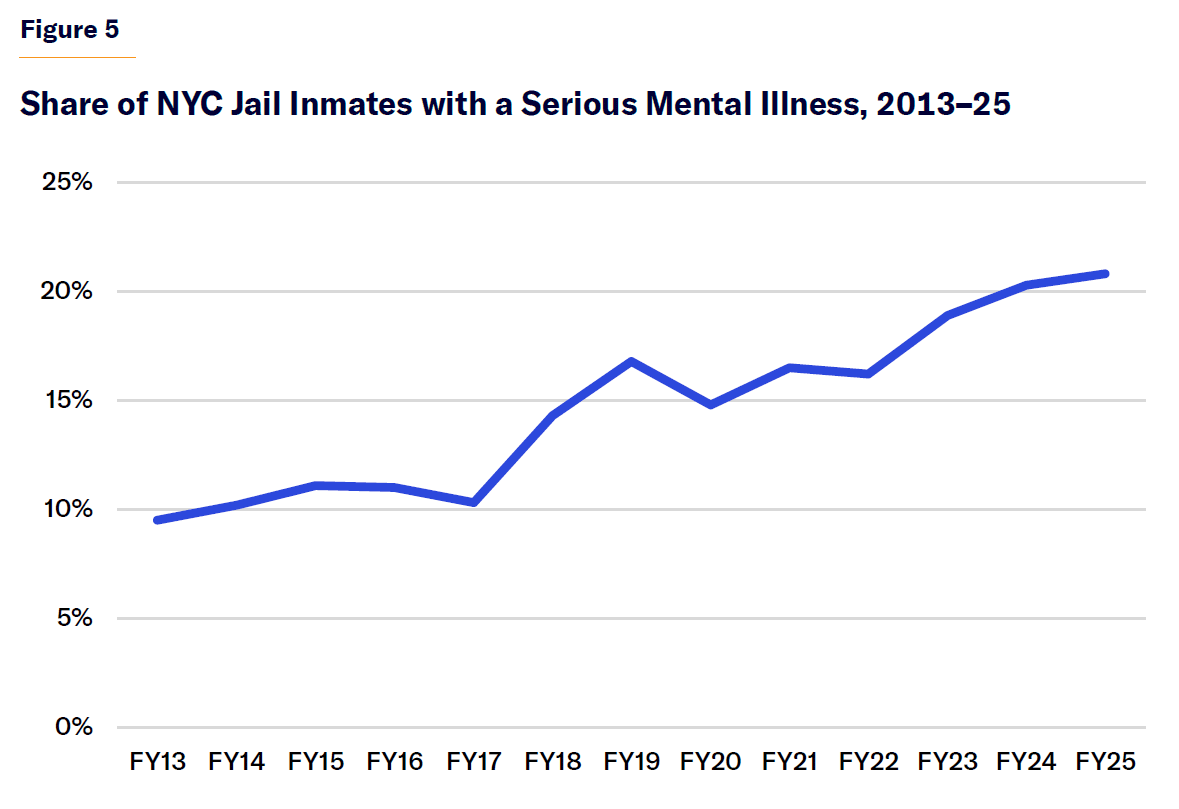

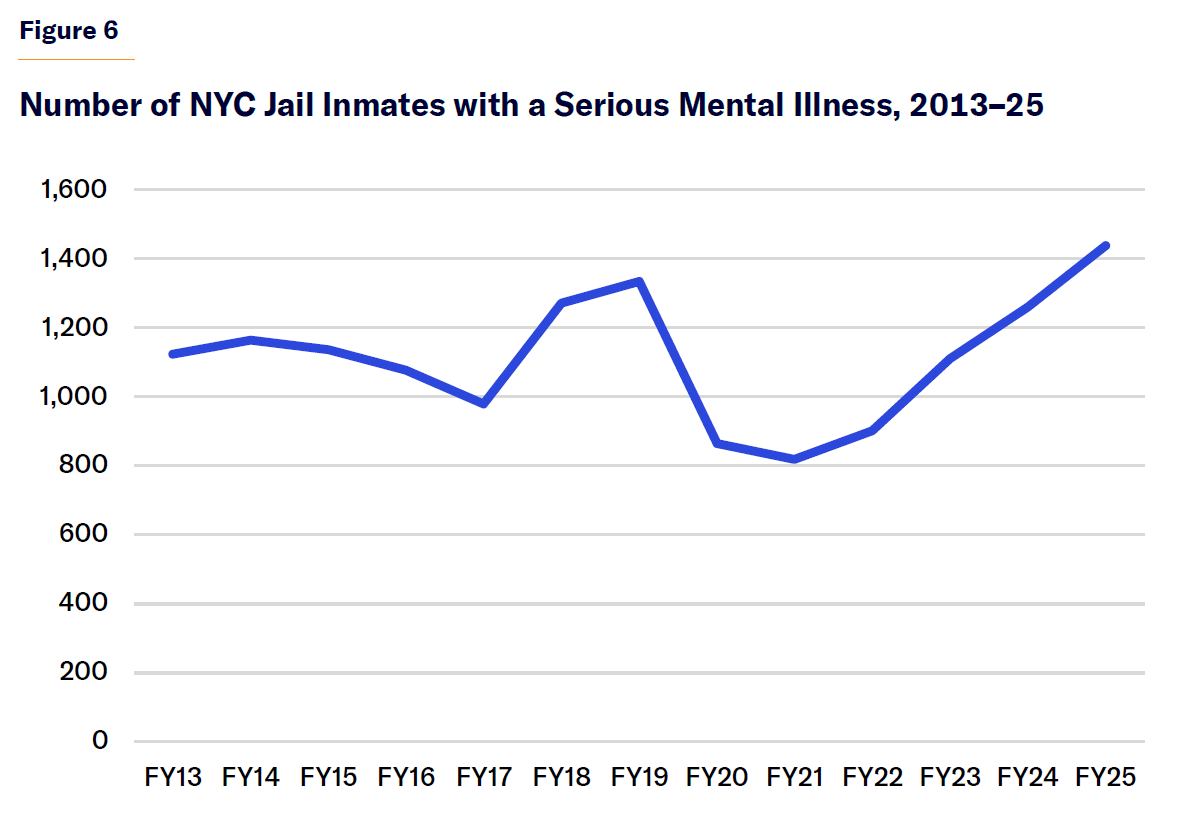

- The number of seriously mentally ill jail inmates and the rate of serious mental illness in the city jail system have continued to rise.

Pressures on city systems remain acute. But the picture is more promising than it was in the late 2010s. Jails aside, NYC service systems are not facing increased pressures since Hochul acted to stabilize New York’s psychiatric hospital bed supply. Challenges lie ahead, though, due to the changing politics of mental health and state financial limitations.

To guide policymakers in this new era of mental health, this report concludes with the following recommendations:

- Continue to replenish bed capacity in specialized state psychiatric centers and in general hospitals.

- Cease relying on the increased number of people using mental health services as a metric of success.

- Insist that state government assert more responsibility over untreated serious mental illness, relative to city government.

Inpatient Mental Health Care in New York

For serious mental illness, inpatient psychiatric services form one crucial part of a continuum of care. Inpatient services may be delivered in specialized psychiatric hospitals, mostly run by the state government; or in general hospitals, which operate under private and public ownership.

In 2014, Governor Cuomo launched the “Transformation Plan” for the Office of Mental Health (OMH). This plan called for reductions in New York’s network of state psychiatric centers, which comprise the remnants of the state asylum system. At its peak, that system included more than 90,000 beds and the largest psychiatric hospital in world history, Pilgrim State on Long Island; and it took up one-third of the state government’s budget.[2] Over the latter decades of the 20th century, and into the 21st century, governors cut thousands of beds and closed several facilities. Governor Mario Cuomo’s term for this process was “reconfiguration,”[3] Governor George Pataki called it “reinvestment,” and Governor Andrew Cuomo called it “transformation,” but the aim was the same: moving mental health resources from psychiatric centers to community-based programs.

Andrew Cuomo came into office in the wake of the Great Recession, when New York faced severe budget difficulties. He pursued financial restructuring on multiple fronts. Inpatient psychiatric care was not then a major driver of health cost inflation, and, as noted, the bed count had been in a decades-long decline. By the early 2000s, about 70% of state mental health resources were going toward community programs.[4] However, on a per-capita basis, inpatient psychiatric treatment is expensive, thanks to regulations meant to ensure quality. The per-patient-per-day cost for state psychiatric centers is $1,396 in the case of non-forensic adults, $3,860 for children, and $1,571 in the case of forensic cases.[5] Relative to other states, New York had (and still has) an above-average complement of inpatient psychiatric beds and facilities.[6] But for mental health officials in the early 2010s, that was a problem.[7]

As was the case with previous waves of deinstitutionalization, officially, OMH saw cutting inpatient capacity as a question of better managing resources for the benefit of the mentally ill. The office justified the cuts this way: “OMH must shift resources to improve the overall health of populations served, improve the outcomes of care and reduce the per-person costs of care. By doing so, OMH can better support the needs of the majority of people in the community—where they do, will, or should reside.”[8]

Cuomo originally pursued closing facilities outright. But after facing opposition, he reoriented to reducing beds, cutting more than 700 by the end of his term. Figure 1 shows the decline in beds in state psychiatric centers from 2014, when the Transformation Plan began, to the present.

Source: “OMH Transformation Plan Status Reports,” NYS Office of Mental Health (OMH)

Source: “OMH Transformation Plan Status Reports,” NYS Office of Mental Health (OMH)

The Hochul Agenda

Cuomo resigned in August 2021 and Hochul took office. Her mental health policies present a mix of continuity and departure from Cuomo’s. At OMH, she has maintained “Transformation” language[9] and the same commissioner, Dr. Ann Marie Sullivan. In keeping with past and global trends in public mental health policy, Hochul has invested in programs to benefit populations other than adults with serious mental illness.[10] At the same time, in a major departure from her predecessors, OMH under Hochul has prioritized inpatient psychiatric care (Tables 1 and 2).

Select Mental Health Policy Changes by the Hochul Administration

Source: “Governor Hochul Announces Major Investments to Improve Psychiatric Support for Those in Crisis,” Office of Gov. Kathy Hochul, Feb. 18, 2022; “Governor Hochul and Mayor Adams Announce Major Actions to Keep Subways Safe and Address Transit Crime, Building on Ongoing State and City Collaboration,” Office of Gov. Kathy Hochul, Oct. 22, 2022; “Governor Hochul Announces Passage of $1 Billion Plan to Overhaul New York State’s Continuum of Mental Health Care,” Office of Gov. Kathy Hochul, May 3, 2023; “Governor Hochul Announces Historic Investments of FY 2025 New York State Budget,” Office of Gov. Kathy Hochul, Apr. 22, 2024; “Mental Health: Inpatient Service Capacity,” Office of NYS Comptroller Thomas P. DiNapoli, March 2024; “Governor Hochul Signs Legislation to Improve Mental Health Care and Strengthen Treatment for Serious Mental Illness as Part of FY 2026 Budget,” Office of Gov. Kathy Hochul, May 9, 2025

In two ways, Hochul’s focus on inpatient treatment was precipitated by the Covid-19 pandemic. First, general hospital systems repurposed hundreds of psychiatric beds in anticipation of Covid overflow.[11] Critical coverage of those changes prompted concerns that systems would use the repurposing as “preludes to permanent closures of inpatient psychiatric beds,” the reimbursement rate for which is less than what hospital systems can receive for other medical services.[12] Second, as Covid shrank the number of beds, it also gave rise to widespread perception of a mental health crisis, which increased demand for inpatient care, particularly among youth.[13]

Table 2

Change in Inpatient Capacity of Psychiatric Centers, 2014–25

Source: “OMH Transformation Plan Status Reports” and “Inpatient Bed Capacity,” NYS OMH, 2025

Other factors motivating more investment in inpatient mental health care in New York included crime and subway disorder, much of which seemed to be connected to untreated serious mental illness.

But Hochul’s fundamental argument was that mental health in New York had a supply problem: the current system lacked capacity to meet demand for inpatient treatment. Accordingly, she worked to expand beds both in the psychiatric centers, which the state controlled, and in general hospital systems, over which the state had indirect control.

Pressures on Other NYC Service Systems

Homelessness

Traditionally, state bed reductions have coincided with increased strains on other NYC systems associated with untreated serious mental illness.[14]

What about Hochul’s bed increases?

To ordinary New Yorkers, homelessness provides the most visible evidence that deinstitutionalization did not fully live up to its initial promise and, more generally, that New York faces a crisis of untreated serious mental illness. Homelessness has several causes, but untreated serious mental illness is a leading factor in the most difficult-to-serve population. One problem with the mentally ill homeless is that they can’t be persuaded to use public services. Another problem is that they overuse certain services.

In NYC, for seriously mentally ill adults, the homeless services system is a far larger operation than jails and hospitals. There are more than 7,000 seriously mentally ill individuals in city shelters (Figure 2), compared with 1,600 in the jails and 4,100 in psychiatric hospital beds.[15] Apart from the state’s mental health policy, New York’s unique “right to shelter” law may play a role in these proportions. In other cities without a right to shelter, homeless services may not play such an outsize role in serving the seriously mentally ill. In 2024, 1,000 individuals discharged from state psychiatric centers were sent to an NYC shelter.[16] By some estimates, nearly half of all single adult shelter clients in the Department of Homeless Services system have a serious mental illness.[17] But, though large, the number of seriously mentally ill sheltered homeless New Yorkers has been decreasing in recent years.

Source: “CoC Homeless Populations and Subpopulations Reports,” U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Exchange

Source: “CoC Homeless Populations and Subpopulations Reports,” U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) Exchange

As the population has declined, the cost to city government has continued to increase. There are 42 mental health shelters in NYC, up from 21 in 2014, when the Transformation Plan began (Figure 3). They have about 5,800 beds and cost about $300 million (Figure 4), a sum funded mainly by city taxpayers. Both the number of mental health shelters and overall cost are much higher than they were in 2014. But the rate of growth has slowed in recent years.

Source: FOIL request from NYC Dept. of Homeless Services

Source: FOIL request from NYC Dept. of Homeless Services

Source: FOIL request from NYC Dept. of Homeless Services

Source: FOIL request from NYC Dept. of Homeless Services

Not all sheltered individuals who are seriously mentally ill are placed in mental health shelters,[18] and shelter-based mental health services are provided to other populations as well. In addition to programs formally designated as “mental health shelters,” which specialize in serving the seriously mentally ill homeless, NYC provides onsite mental health services in about two dozen other shelters, with an annual cost of $125 million.[19] Thus, the total cost for shelter programs run by NYC that provide mental health care to their homeless clients exceeds $400 million.

NYC is also home to 40,000 units of permanent supportive housing.[20] No specific reporting is done about the rate of serious mental illness among permanent supportive housing tenants; but many programs in the past have used—and the city’s current “Coordinated Assessment and Placement System” uses—serious mental illness as one criterion for eligibility.[21] In New York, supportive housing was first developed at scale as a partnership between the city and state. The state’s involvement was predicated on the idea that misguided state mental health policy had contributed to homelessness in New York City.[22]

City officials tend to see the high concentration of seriously mentally ill individuals in city shelters as a problem. By contrast, the high concentration of serious mental illness in supportive housing is considered a success. As many see it, supportive housing is where seriously mentally ill individuals should be, as opposed to the streets, shelters, and psychiatric hospitals. However, some recent press reports indicate that at least some supportive housing tenants would benefit from a higher level of care, such as what a psychiatric hospital would provide.[23] Research about permanent supportive housing has shown it to be less successful at improving health outcomes than at achieving housing stability,[24] which suggests that the press reports may not be purely isolated, anecdotal incidents.

Significant interest, going back decades, has been devoted to fighting the “criminalization of mental illness,” an idea premised on the idea that many incarcerated Americans would be better served under the care of the public mental health system. There has been less interest in determining how many individuals now in homeless services programs would be better served in the public mental health system.

Criminal Justice System

The raw number of seriously mentally ill inmates, as well as the rate of serious mental illness among the city’s jail population, has increased steadily since Covid (Figures 5 and 6). As of June 2025, the number stands at about 1,600.[25] That figure far exceeds the bed count of NYS’s largest psychiatric hospitals (Rockland State and Creedmoor each have about 340 adult beds).[26]

Source: “Mayor’s Management Reports,” NYC Mayor’s Office of Operations; “CHS Patient Profile for Individuals in the New York City Jail System,” NYC Health + Hospitals

Source: “Mayor’s Management Reports,” NYC Mayor’s Office of Operations; “CHS Patient Profile for Individuals in the New York City Jail System,” NYC Health + Hospitals

Source: “Mayor’s Management Reports,” NYC Mayor’s Office of Operations; “CHS Patient Profile for Individuals in the New York City Jail System,” NYC Health + Hospitals

Source: “Mayor’s Management Reports,” NYC Mayor’s Office of Operations; “CHS Patient Profile for Individuals in the New York City Jail System,” NYC Health + Hospitals

One underappreciated feature of the so-called trans-institutionalization of the seriously mentally ill has been the cost shift from states to cities. States run mental institutions; jails are run by cities and counties. Thus, cities and counties bear the fiscal burden of jail inmates who, under a different order, would be patients at psychiatric institutions that are paid for by state governments.[27] Incarcerated Americans have a right to health care, including mental health, but services are not Medicaid-billable. Thus, those constitutionally mandated costs are primarily funded out of the correctional agency’s budget. In NYC’s case, the city spends about $300 million on jail health care.[28]

How does New York’s large population of mentally ill jail inmates affect the plan to close Rikers jail? The city government is currently building four jails, based in Brooklyn, the Bronx, Manhattan, and Queens, to replace the jail complex on Rikers Island. From the beginning, the city jail population’s high rate of mental illness influenced the plan architects’ underlying contention about incarceration’s harms, and has shaped the plan’s approach to jail design. As part of, and in concert with, the “Borough-Based Jails Plan,” New York is investing heavily in specialized housing for mentally ill inmates.[29]

But the city jail population’s high rate of mental illness also contributes to the Borough-Based Jails Plan’s uncertain future. The total jail population now stands at more than twice the capacity of the new jail system.[30] At about 1,600, the current seriously mentally ill population alone stands at close to half the new jail system’s capacity. New York is already host to scores of community-based alternatives to incarceration, including programs specifically for mentally ill offenders, such as mental health courts.[31] The overwhelming majority of NYC jail inmates are being held on felony charges.[32] If city government wants to close Rikers, major reductions in the seriously mentally ill felon population are a necessity, and it is very difficult to see how that can be accomplished without the use of psychiatric institutions.

Untreated serious mental illness also burdens the police department, which responds to about 170,000 “emotionally disturbed person” (EDP) calls per year. This rose during the Transformation Plan and has remained elevated, though it has not been rising recently (Figure 7).

Source: “Use of Force,” NYPD press office

Source: “Use of Force,” NYPD press office

High levels of police involvement in handling mental health crises have motivated New York to invest in training (last year, uniformed NYPD personnel received over 18,000 hours of “crisis intervention training”)[33] and new programs. Generally, those new programs aim at reducing police involvement in untreated serious mental illness. Though some such programs have been launched by MTA and the governor (Subway Co-Response Outreach SCOUT[34] and Safe Options Support),[35] NYC government’s role has been especially active, with the Partnership Assistance for Transit Homelessness (PATH),[36] B-Heard[37] programs, and numerous homeless outreach initiatives. Leading candidates in the city’s 2025 mayoral election, such as Zohran Mamdani,[38] have proposed expanding alternative response models.

Seriously mentally ill individuals could benefit from a well-designed co-response, or alternative response, or outreach model. But doing it right will require hiring credentialed, and thus well- compensated, health professionals and ample psychiatric hospital capacity in which those who need inpatient commitment may receive it. Quality alternative response won’t save money on police (since, among other reasons, those programs often wind up dealing with different problems from what the police deal with)[39] and will require more, not less, spending on psychiatric beds.

City Hospitals

Table 3 presents trend data in general hospital psychiatric beds over the course of the Transformation Plan period. Of the 9,200 inpatient psychiatric beds in NYS, slightly more than half are located in general hospitals.[40] General hospitals became major providers of inpatient psychiatric services during deinstitutionalization. The same financing programs that de-incentivized care in the massive specialized psychiatric institutions that made up the traditional system incentivized it in wards located in general hospitals,[41] which improved access to hospital care—there are far more general hospitals than state institutions. In some cases, general hospital programs were developed in concert with community mental health centers.[42] General hospital psychiatric units have small bed counts meant to service short-term stays, in contrast to the large state hospitals meant to service intermediate and long-term stays.[43] Of New York’s 24 psychiatric center programs, 15 have more than 100 beds. Of New York’s 84 psychiatric programs in general hospitals, only 14 have more than 100 beds.[44] The median length of stay for adults (non-forensic cases) at state psychiatric centers is 471 days; the average length of stay for adults in general hospitals is 14–15 days.[45]

Table 3

Trends in General Hospital Psychiatric Beds, 2014–25

Source: “OMH Transformation Plan Status Reports”

Nationwide, hospital networks’ commitment to inpatient psychiatric care has weakened because it is reimbursed at much lower rates than other medical procedures.[46] According to a 2020 report by the NYU Nurses Association, the average general hospital bed in NYS, in 2018, generated $1.6 million in net patient revenue, while the average psych bed generated only $88,000.[47] In the late 2010s, NewYork-Presbyterian converted the Allen Pavilion, a 30-bed psychiatric unit, to an expansion of a spinal center.

Governor Hochul did three things in response to bed cuts in general hospitals: she pushed for beds repurposed during the Covid era to be restored to use as psychiatric care beds (and this was enforced through fines; most, though not all, beds have been restored); provided $50 million in capital funding to expand psychiatric units in hospitals, across the state; and boosted the Medicaid reimbursement rate.[48]

It should be emphasized that psychiatric bed losses in general hospital systems were not caused by the Transformation Plan, which concerned state psychiatric centers, OMH-run facilities that provide only mental health care. OMH licenses private nonprofit hospitals but does not operate or fund them. Private health systems’ retreat from inpatient care was well under way by the time the Transformation Plan had begun.[49] The larger context of unstable trends in general hospital– based care made the plan much riskier and difficult to justify. Fewer beds overall make patient “flows” more complicated to manage. A 2022 report published in Crain’s New York Business cited a waiting-list estimate of months for beds in state psychiatric centers.[50] The system, as a whole, is under strain: when patients in general hospitals can’t be moved to state psychiatric centers, that means fewer open general hospital beds for those trying to access them.

And that means more pressure on city hospitals. NYC Health + Hospitals is a $2 billion, 41,000-employee[51] health agency under mayoral control, making it an indispensable instrument in the crafting of mental health policy at the city level. NYC Health + Hospitals operates about half of all psychiatric hospital beds in the city[52] and devotes a much larger share of its total bed capacity to psychiatric services than private hospital networks do.[53] In recent years, private nonprofit health systems have retreated from inpatient psychiatric care, even as demand for that mode of care has increased, thus shifting a major cost burden onto public hospitals.

Conclusion: Mental Health After Deinstitutionalization

New York reached the midpoint of the 2020s with more state psychiatric beds than it entered the present decade with.[54] Bed reductions, in the near term, seem unlikely. Thus, the 2020s will probably be the first decade since the 1950s in which the state gains public psychiatric hospital beds. Deinstitutionalization in New York, at long last, has concluded.

During the 2010s, under Governor Cuomo, the state government cut beds in psychiatric hospitals and NYC service systems were strained. In the mid-2020s, under Governor Hochul, the bed supply has stabilized. Pressures on city systems, with the exception of jails, are no longer increasing at the rate that they were during the 2010s. In homeless services, while the number of mental health shelters has increased since 2014, the number of seriously mentally ill sheltered homeless individuals has recently declined. Police EDP calls remained elevated, though they are not rising. The recent stabilization of New York’s bed supply may have helped ease—though it has not eliminated— pressure on city systems.

Further reform may be complicated. Fiscal experts, such as the Citizens Budget Commission and the state comptroller, have raised doubts about the sustainability of recent state spending trends.[55] The politics of mental health, especially under Hochul, are heavily determined by budget capacity. Hochul’s pursuit of a “comprehensive” approach to mental health policy, including broad-based workforce raises, and interventions less germane to untreated serious mental illness, such as teen Mental Health First Aid, has drawn praise from advocates.[56] Managing the mental health coalition may be harder if the budget is tighter.

Other factors likely to influence the politics of mental health include the result of the 2025 NYC mayoral race. Mayor Eric Adams has been a consistent advocate for state action on untreated serious mental illness,[57] but his reelection prospects are uncertain. There may also be less political will to address untreated serious mental illness if crime continues to be eclipsed by other areas of public concern.

To some extent, Hochul may be hindered by her success. For example, in arguing for the appropriateness of changing the state commitment standard during the recent FY26 budget cycle, the Hochul administration argued that New York already had enough psychiatric beds to accommodate any new resulting inflow.[58] This may complicate the case for further inpatient capacity expansions.

Still, Hochul has presided over a historic change. Over the decades, deinstitutionalization was marked by ever-tighter restrictions on civil commitment. Hochul changed state law to loosen restrictions on civil commitment. References to “unnecessary” and “vacant” beds, once ubiquitous in OMH’s annual budget “briefing book” documents, ceased in FY24.[59] The term “right-size” was once constantly used to characterize bed reductions;[60] more recently, state officials have used that term to characterize adding beds to state psychiatric centers.[61] Whereas past governors celebrated the “efficiency” realized by their bed cuts, Hochul has celebrated overseeing “the largest expansion at [state psychiatric centers] in decades.”[62] And no psychiatric center has been closed since Middletown, in the Hudson Valley, about two decades ago.[63]

To continue to strengthen New York’s mental health system and to expand access to inpatient psychiatric care, New York should take the following actions:

Recommendations

First, continue to replenish bed capacity in specialized state psychiatric centers and in general hospitals. A 2008 report by the Treatment Advocacy Center, an organization focused on improving the lives of seriously mentally ill Americans, recommended about 50 public psychiatric beds per 100,000 population. At that time, NYS’s bed rate was 27.4 per 100,000, which the Treatment Advocacy Center considered a “serious bed shortage.”[64] NYS now has 18 beds per 100,000.[65]

During and after the Covid pandemic, New York’s mental health system experienced a rise in demand for services, including hospital-based care. That should not have been seen as a cultural aberration caused by extraordinary pandemic conditions but evidence of an underlying crisis of untreated serious mental illness.[66] The historical tendency of policymakers is to categorize New York’s above-average bed capacity[67] as a liability. They should instead start characterizing it as an asset and source of pride, much as they do with other health, housing, and social services programs that NYS spends more on than other states.

The seriously mentally ill need more than just hospital beds. Appropriate care for those afflicted with chronic conditions, in particular, will require New York’s mental health system to provide a variety of long-term residential options. But those programs will be best positioned for success when they’re not responsible for clients needing a higher level of care than the program can provide.

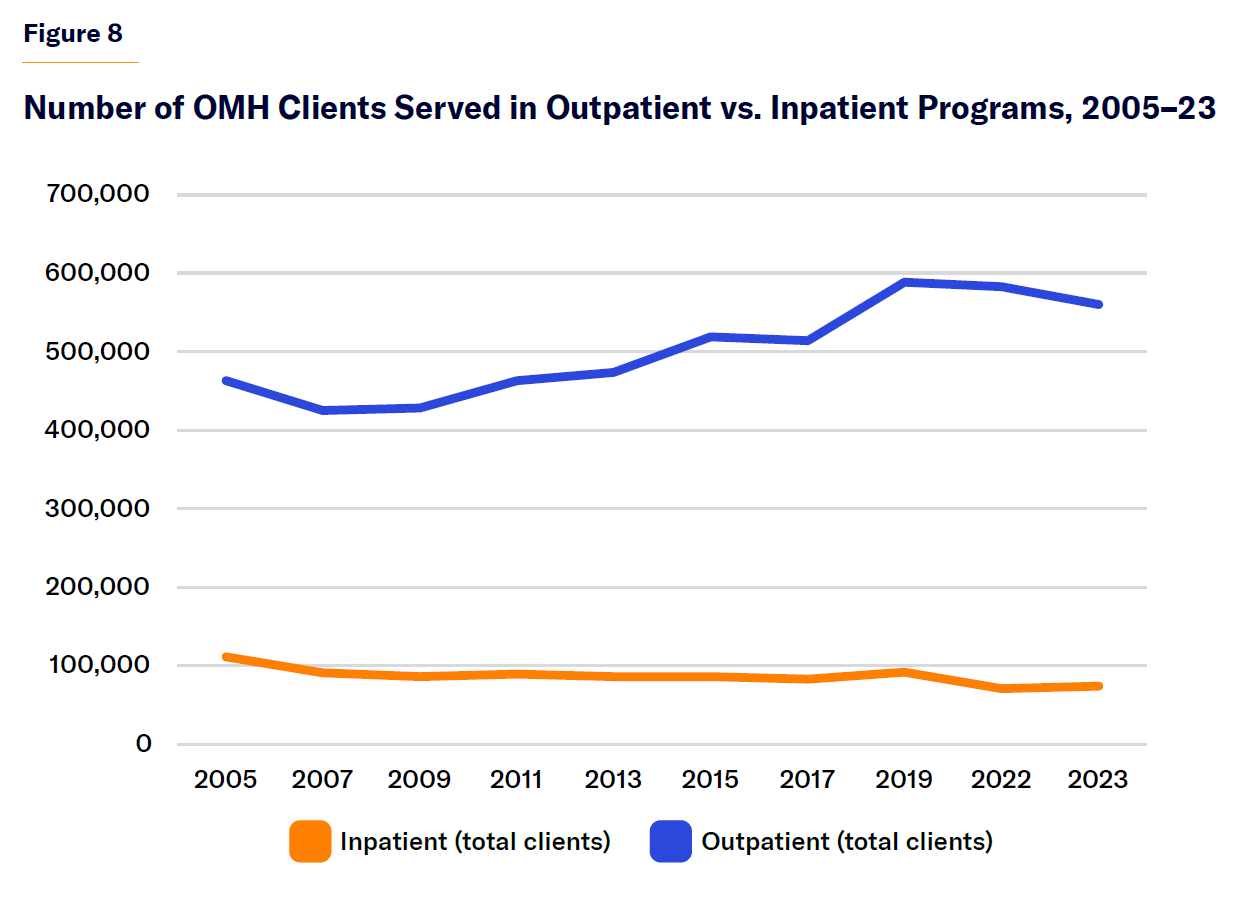

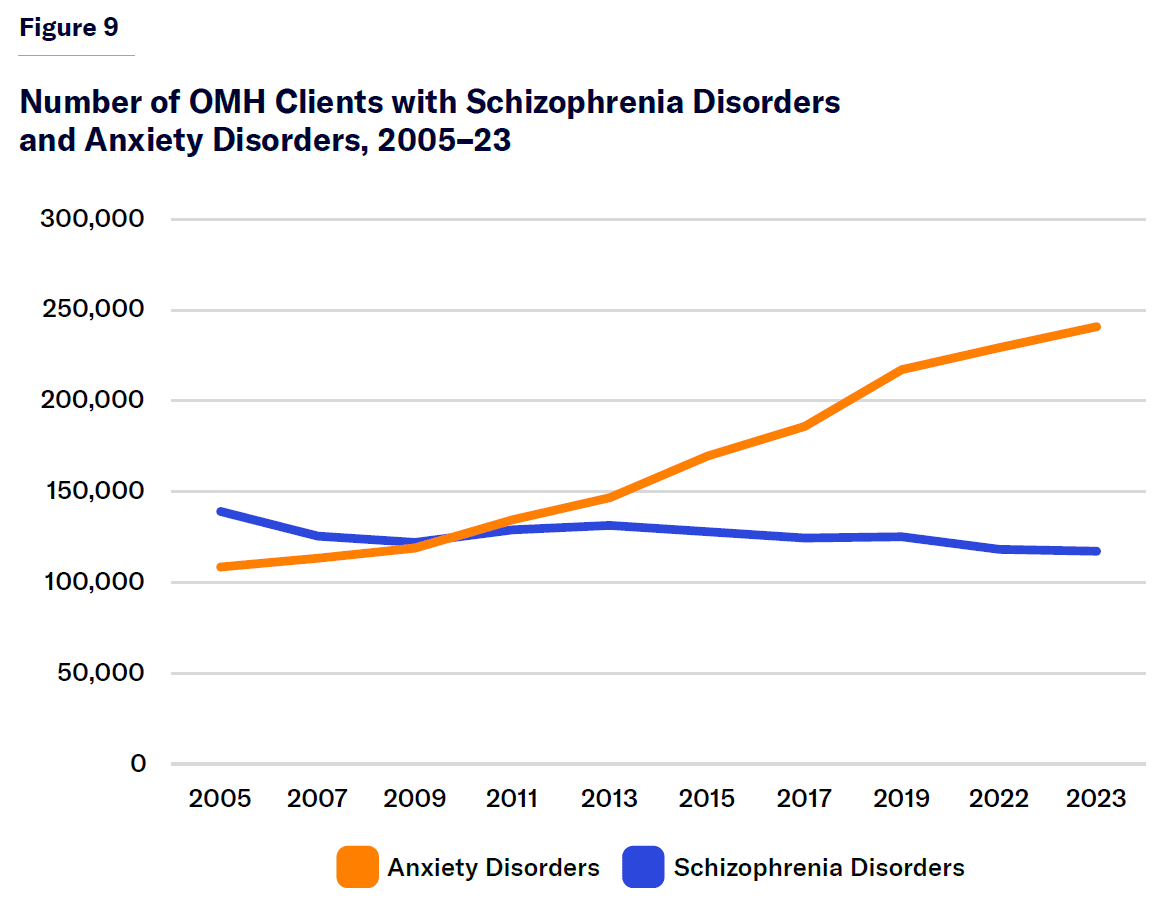

Second, cease relying on the increased number of people using mental health services as a metric of success. One point of continuity between the Cuomo- and Hochul-administered Transformation Plan is the use of the number of individuals as a sign of policy success.[68] Who is served by the system, and their level of need, is more important than how many people have received services. According to OMH data, the shift in services from inpatient to outpatient services (Figure 8) has coincided with a rise in the number of people with anxiety disorders served by the system and a decline in the number of people with psychotic disorders served (Figure 9).

Source: “R7: Clinical and Functioning Trends,” OMH Patient Characteristics Survey

Source: “R7: Clinical and Functioning Trends,” OMH Patient Characteristics Survey

Source: “R7: Clinical and Functioning Trends,” OMH Patient Characteristics Survey

Source: “R7: Clinical and Functioning Trends,” OMH Patient Characteristics Survey

One standard premise of deinstitutionalization was that many confined to long-term institutional programs could be more appropriately served in community programs. But a traditional problem with shifting resources from institutional to community programs was that sometimes the latter wound up serving different, less troubled, patients than the former.[69] The Transformation Plan, from the outset, has been accompanied by regular reporting about where the resources freed up by eliminating the number of beds went, although the state comptroller has questioned that reporting’s rigor.[70] More generally, the state should use a different metric from the number of individuals served, such as success in reducing homelessness and incarceration.

Third, insist that state government assert more responsibility over untreated serious mental illness, relative to city government. Although Mayor Eric Adams differs in many ways from Mayor Bill de Blasio, both assumed responsibility for mental health. De Blasio’s “Thrive NYC” initiative applied a comprehensive, public health–style approach to mental health. Thrive NYC was criticized for its diffuseness. Adams has taken a more focused approach, concentrating on involuntary treatment and serious mental illness. Both efforts have confounded how the state and city should share responsibility for untreated serious mental illness. Accountability is a traditional shortcoming of American mental health, as is the case with many fields in the human services involving multiple levels of government and extensive use of nonprofit contractors.

City officials tend not to appreciate it when the state government pushes costs down to the local level. But that can happen with varying degrees of abruptness. City officials in the 21st century tend to be only dimly aware that untreated serious mental illness was once entirely a state responsibility. In large measure, it still should be so. State government—because of factors such as the state’s control over psychiatric centers and Medicaid, the importance of which in mental health cannot be overstated[71] —should have the lead in confronting New York’s crisis of untreated serious mental illness.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Judge Glock and Julie Sandorf for comments on the draft; and the Charles H. Revson Foundation for support.

Endnotes

Photo: Wiyada Arunwaikit / iStock / Getty Images Plus

Are you interested in supporting the Manhattan Institute’s public-interest research and journalism? As a 501(c)(3) nonprofit, donations in support of MI and its scholars’ work are fully tax-deductible as provided by law (EIN #13-2912529).