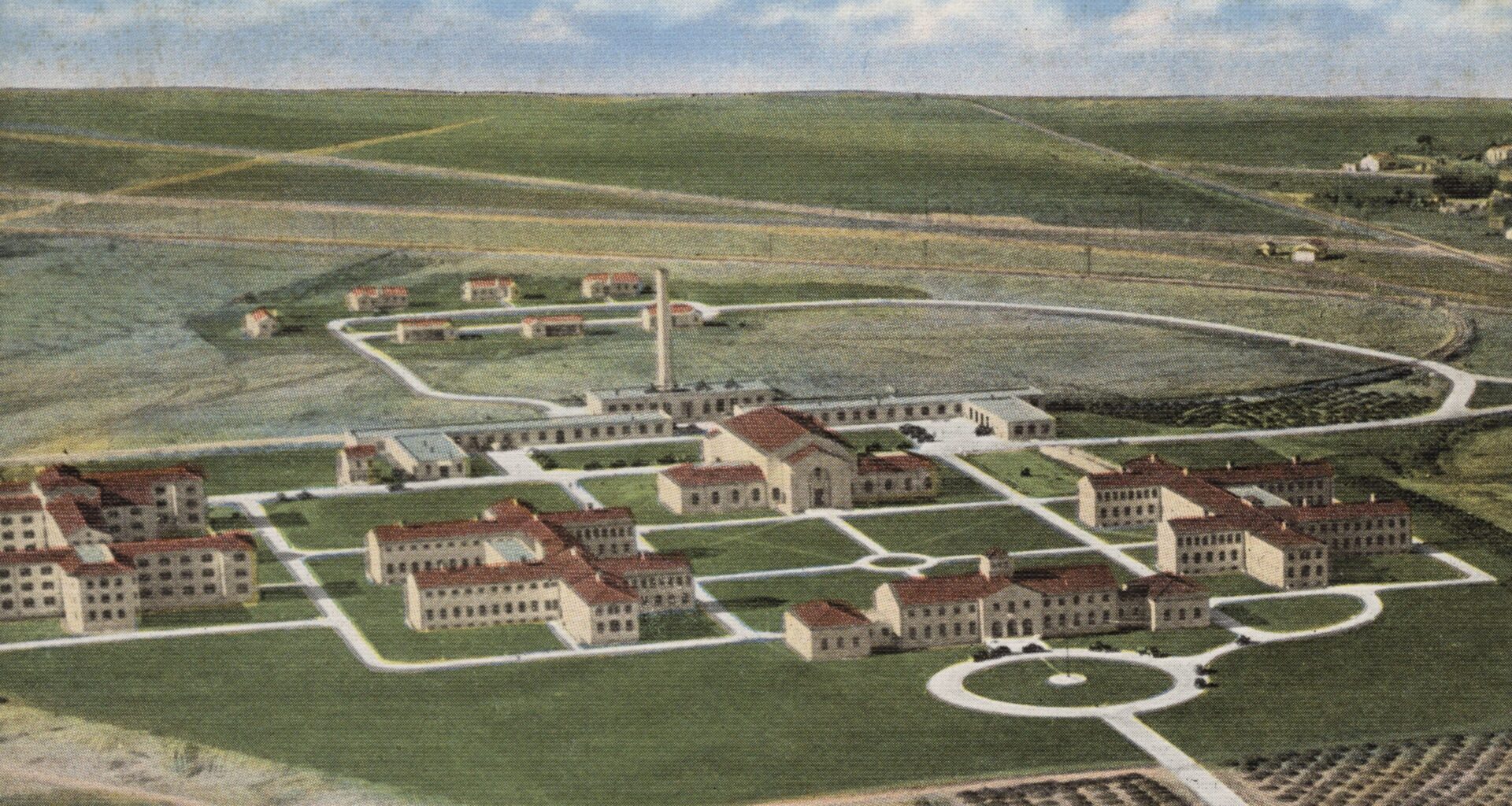

Fort Worth won a big federal contract in 1931, at $4.5 million, the largest ever for the state at that time; today, few remember much about it.

The building contract was for the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm, which treated patients from 1938 to 1971, as one of two hospital prisons that promised a less punishment-focused approach for people who used drugs. The federal dollars helped Fort Worth become home to the only federally funded drug treatment program west of the Mississippi.

The farm was a place for federal prisoners who had been ensnared in new drug laws that made once over-the-counter remedies like cocaine illegal. It also housed patients voluntarily seeking treatment. The idea of the farms, established through the 1929 Narcotic Farms Act, was to blend psychiatric treatment, physical rehabilitation and vocational training and help transform American treatment policies.

But as Holly M. Karibo recounts in her recent book, “Rehab on the Range: A History of Addiction and Incarceration in the American West,” the reality of the treatment centers would turn out to be much more complicated particularly as cultural changes impacted the treatment of addicts and incarceration policies.

“Rehab on the Range” was released on Nov. 19 from University of Texas Press as part of its American Studies Series.

Karibo and Debbie Russell, author of “Crossing Fifty-One,” a story that includes a section on her grandfather’s time at the narcotic farm, will be speaking at 2 p.m. Sept. 13 at the Fort Worth History Center, 501 E. Bolt St., about the Fort Worth institution.

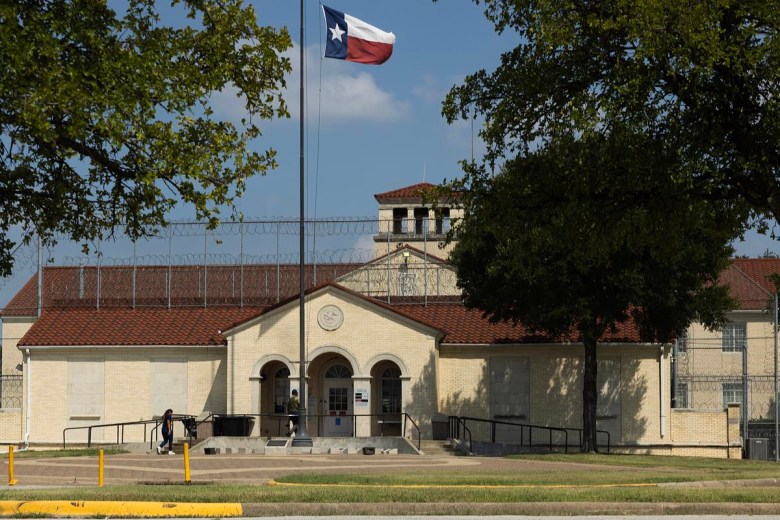

The building that housed the facility is still extant, now the Federal Medical Center Fort Worth, a prison medical center in the southeast part of the city administered by the Bureau of Prisons and closed to the public.

The Fort Worth facility was one of two maintained by the federal government. The other was in Lexington, Kentucky. Both opened at a time when the government and the public were seeking answers to drug use spreading among the population.

In the book and film version of “The Man with the Golden Arm,” protagonist Frankie Machine — played by Frank Sinatra in the movie — says he has just come back from Lexington, which was a euphemism for undergoing drug treatment, said Karibo, an Oklahoma State University history professor.”

“‘Going to Lexington’ was a way of saying you were going to try to kick your habit,” she said. “Lexington sort of got into the culture in a way Fort Worth never really did,” she said.

Karibo’s book takes readers through a history of addiction treatment through the lens of the development of the narcotic farm model as a new way to treat those suffering from addiction.

“It’s fascinating to read and hear the differences in approach toward drug treatment over the years and how it shifted so much, eventually toward regarding it more as criminal behavior,” she said.

Prison officials were originally very supportive of this idea because they worried that having contraband in the prisons was disrupting the hierarchies of prison culture, Karibo said.

“They saw it as a solution to kind of shuffle them out, while reformers and scientists and people interested in addiction saw it as an opportunity to actually do some good, to provide a more humane treatment approach, rather than punishment,” she said.

Amon G. Carter weighs in

While the Kentucky facility served the East Coast population, the government wanted a more western facility and chose Fort Worth with some persuasive lobbying from the city’s powers-that-be, in particular Fort Worth Star-Telegram owner and Fort Worth booster Amon G. Carter. The House committee selecting the location saw 38 cities competing to land the project.

Carter went so far as to lobby the surgeon general in person, according to Karibo. The surgeon general then passed the Fort Worth publisher’s thoughts about the city’s ideal location on to the chairman of the selection committee.

Fort Worth’s pitch was that the city was on the upswing in terms of development and growth and pointed to the modern railway system and the airlines serving the area, allowing patients ease of access to and from the hospital. And it was, after all, where the West begins, Karibo said, using one of Carter’s favorite phrases.

“Fort Worth did have a good point,” she said.

But there were other reasons Fort Worth and Texas made sense, said Karibo, who has studied the drug subcultures of Texas and Oklahoma.

“Fort Worth was uniquely situated, in part because of Texas’ location on the border, because that was essentially the way the drug trade flows,” she said.

Fort Worth’s location and transit connections, even in the 1930s with its rail lines and nascent aviation industry, were key to the city’s economy at the time. That also included the underground economy related to drug culture of the time.

The drug connection

Fort Worth was within the nexus of the drug trade and drug culture related to Kansas City and Oklahoma City, as well as New Orleans, which was a key hub, Karibo said.

“That was true and they had to know that as well, but it made North Texas a particularly important area to cover. The drugs were flowing through here,” she said.

The site chosen was about 7 miles from the city center, but as the city leaders advertised, there was adequate transportation to that area. There was also open land to put the inmates to work on the farm, and ranch facilities were part of the setting and the treatment.

The construction of the initial $4.5 million campus, coming at the tail end of the Great Depression, was invaluable, as would be the jobs brought by the facility’s construction.

“These were good paying federal jobs at a time when people were struggling,” said Karibo. “It was a big deal.”

City leaders thought that if cattle, oil and railroads had built the city, the narcotic farm could lead it to greater wealth as a leader in health care and rehabilitation, according to Karibo.

When it opened, the campus consisted of five main buildings all consisting of yellow brick and topped with red tile roofs. The building appears to use brick from Fort Worth’s Acme Brick, though a company spokesperson said they had not yet found records to prove it. The design included a tunnel system between the buildings that was apparently a relief to the workers during the hot summers. The hospital initially was home to 285 patients, but that gradually increased to about 1,000 with the construction of an additional dormitory.

And it was an actual farm. The location was used to develop vocational skills, and patients raised cows, pigs and chickens. At one point, the facility produced enough milk to feed the prison’s population.

Over the years, the Fort Worth facility and its sister campus in Kentucky treated more than 60,000 patients.

“Rehab on the Range” by Holly M. Karibo. (Courtesy photo | University of Texas Press)

“Rehab on the Range” by Holly M. Karibo. (Courtesy photo | University of Texas Press)

If You Go …

What: From 1938 to 1971, Fort Worth was home to one of two federal drug rehabilitation centers in the United States. Two authors of books on the Fort Worth facility will delve into the history of the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm.

Who: Debbie Russell, author of “Crossing Fifty-One,” and Holly Karibo, author of “Rehab on the Range,” will present their research and discuss their books, followed by a Q&A.

When: 2 p.m. Sept. 13.

Where: Fort Worth History Center, 501 E. Bolt St.

For more information, go here.

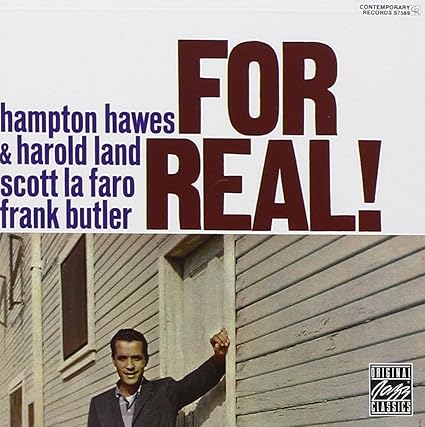

And, it should be noted, the prison band swung with abandon even if the players were — at least allegedly — straight, said Karibo. Lots of drug-addicted musicians found their way there either as part of their punishment or on a voluntary basis. One was premier jazz pianist Hampton Hawes who wrote about the experience in his autobiography, “Raise Up Off Me.”

Hampton Hawes album, “For Real!” from Contemporary Records. (Courtesy photo | Contemporary Records)

Hampton Hawes album, “For Real!” from Contemporary Records. (Courtesy photo | Contemporary Records)

“Well, we cooked pretty good,” Hawes recalled. In his book, Hawes talks about the Texas “cracker guards” watching the players swinging well past curfew and shaking their heads in disbelief.

Some prisoners, including Hawes, got day passes, said Karibo. He played occasional gigs as well as led the band at the farm. Hawes eventually received a pardon from President John F. Kennedy and resumed his career outside of Fort Worth.

Karibo said the results of the narcotic farms’ treatments are difficult to judge because the ideas behind the program changed with the culture.

“There was tension between voluntary patients going through a treatment program and involuntary criminal patients who were sometimes more violent,” she said.

Then, during World War II, the facility began to provide psychiatric care for soldiers, adding another layer of complexity.

All those shifts and demographic changes made it difficult to sustain the model program that began in the late 1930s.

“The farm was presented as a place that was based on therapeutic care models,” Karibo said. “In the end, it wasn’t really that.”

Cultural shift on treatment

Eventually, the culture began to tilt toward criminalizing drug use, she said.

Despite efforts of local officials, as well as Texas Sen. Ralph Yarborough, the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm closed in 1971. The Lexington farm closed in 1967.

The Fort Worth Federal Medical Center, once the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm, is located off of Horton Road in Fort Worth Aug. 6, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

The Fort Worth Federal Medical Center, once the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm, is located off of Horton Road in Fort Worth Aug. 6, 2025. (Maria Crane | Fort Worth Report/CatchLight Local/Report for America)

The Fort Worth facility is now used as a hospital for federal prisoners and the area around it has filled in along the southern edge of Loop 820, including with the nearby O.D. Wyatt High School and Tarrant County College South Campus.

The facility was most recently in the news when Joseph Maldonado-Passage, better known as “Tiger King” or Joe Exotic, was reported to be ill and incarcerated at the Federal Medical Center Fort Worth. He has been there since 2020 after being transferred from a federal prison in Oklahoma.

Now an Oklahoma State University associate professor of American history, Karibo became interested in the Fort Worth Narcotic Farm when she was working at Tarleton State University and noticed a cluster of 1930s-era buildings just off Loop 820 in south Fort Worth.

She has always been interested in border economics and drug cultures, so when she discovered what those buildings were she began to research the history behind them.

“The federal archives are there in Fort Worth, so really not that far from where the farm was, and there was plenty of information on it,” she said.

While the history is interesting and important, Karibo notes that there is talk of going back to a more treatment-oriented version of drug treatment for prisoners.

“We’ve heard some of that talk from Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and this idea of drug farms, which is similar, so the idea is out there,” she said.

The idea of the drug farms would be to build up the morale of the addicts and give them a work ethic, said Karibo, but based on the experiences from the Fort Worth and Lexington experiments, it doesn’t look like an effective treatment.

“The tough part is the recidivism rates were so high at Fort Worth and Lexington that it’s hard to argue it was a success,” she said.

“It was probably better than a straight prison, but in terms of the number of people who returned to drugs from these institutions, that rate was really quite high from opening to closing. Ultimately, it didn’t seem to actually be effective in implementing even the most modern treatment efforts.”

Bob Francis is business editor for the Fort Worth Report. Contact him at bob.francis@fortworthreport.org.

At the Fort Worth Report, news decisions are made independently of our board members and financial supporters. Read more about our editorial independence policy here.

Related

Fort Worth Report is certified by the Journalism Trust Initiative for adhering to standards for ethical journalism.

Republish This Story

Republishing is free for noncommercial entities. Commercial entities are prohibited without a licensing agreement. Contact us for details.