Prize Winners’ Discovery of Genomic Imprinting Opened the Door to Epigenetics

Developmental biologists Davor Solter and Azim Surani will receive the Paul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmstaedter Prize 2026, the Scientific Council of the Paul Ehrlich Foundation announced today. The prizewinners discovered the phenomenon of genomic imprinting. In mammals, this means that the genetic materials of eggs and sperms are functionally different. In addition to their genetic information, some genes carry a molecular mark that prevents their genetic information to be active in the embryo. This why we need the full genetic input from both mother and father. This discovery shook the foundation of classical genetics and opened the door to the vast field of modern epigenetics.

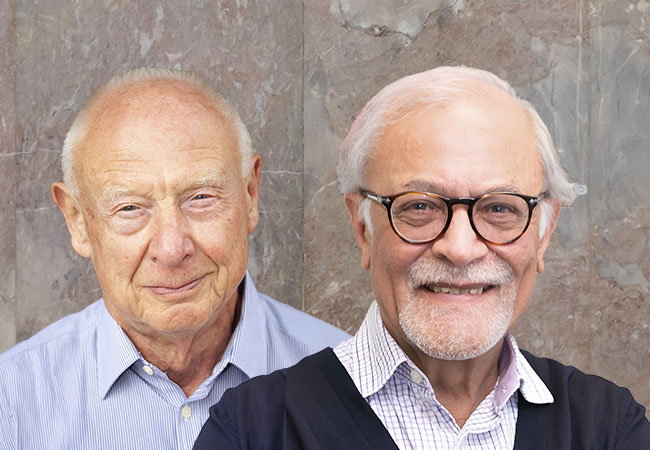

Copyright: David Solter (left, privat); Azim Surani (Jacqueline Garget, University of Cambridge)

Copyright: David Solter (left, privat); Azim Surani (Jacqueline Garget, University of Cambridge)

The genes that carry our genetic information are packed together in the chromosomes of the cell nucleus. There are 22 autosomes as well as the sex chromosomes X and Y. Each germ cell contains a single set of 23 chromosomes. Each somatic cell contains a double set of chromosomes – one inherited from the mother’s egg, the other from the father’s sperm. This means that all body cells contain two copies of each gene. These copies, which can occur in different versions (alleles), are both used as blueprints for producing RNA molecules that are then translated into proteins. Both gene copies can influence a child’s appearance (phenotype). If one copy is mutated or damaged, the other usually compensates and takes over its function. Solter and Surani partially upended these basic principles of classical genetics when they discovered that mammalian parents apparently pass on only one active copy of some genes to their offspring. “This discovery was a turning point in modern genetics,” explains Prof. Thomas Boehm, Chair of the Scientific Council. “It showed that our phenotype is not determined by genotype alone, but also shaped by epigenetic marks. That fundamentally changed our understanding of health and disease.”

In the early 1980s, Davor Solter in Philadelphia (USA) and Azim Surani in Cambridge (UK) set out – independently and simultaneously –to solve a fundamental genetic puzzle: Why is a virgin birth (parthenogenesis) not possible in mammals? After all, female ants, bees, lizards or snails, for example, can reproduce without a male contribution, allowing their offspring to develop from unfertilized eggs. Solter and Surani answered this question by independently applying a technique Solter had previously developed and refined, namely the transplantation of germ cell nuclei. After fertilization, the nuclei of egg and sperm remain temporarily separate – at this stage, they are called pronuclei. Solter and Surani then replaced one of the two pronuclei with that of a donor from another mouse strain, generating embryos with either two maternal or two paternal pronuclei. Unexpectedly, none of these embryos survived. In combinations of two paternal pronuclei, the embryonic tissues developed poorly, whereas the placental tissues were largely unaffected. Conversely, in combinations with two maternal pronuclei, the placental tissues failed to develop normally, leading to malnourishment of the embryo.

Only embryos in the control group, arising from one male and one female pronucleus, developed into healthy mice. The two researchers concluded that in mammals, maternal chromosomes contribute essential information that is missing in the paternal chromosomes – and vice versa. Both parental chromosome sets must be transmitted in their entirety for offspring to develop normally. Surani coined the term genomic imprinting to describe the phenomenon that some genes are transmitted in active form only by the mother and others only by the father. Soon afterwards, researchers discovered that the molecular markers involved in imprinting consist primarily of tiny methyl groups attached to one of DNA’s four bases.

Seven years after the discovery of the two prizewinners, in 1991, the first imprinted genes were identified: IGF2R, a growth-inhibiting gene expressed only from the maternal allele, and IGF2, a growth-promoting gene expressed only from the paternal allele. This supported the idea that genomic imprinting evolved as a mechanism to regulate fetal growth in the womb, helping to maintain a healthy balance between the interests of the embryo to grow and that of the mother to prevent excessive contribution of her own bodily resources. Evolution may have introduced this strategy to make uterine development in mammals possible in the first place. In fact, most known imprinted genes – they make up around one percent of our genome – are involved in balancing growth signals and brain development. In Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, the growth processes of individual organs become imbalanced, or they develop asymmetrically during embryogenesis; Angelmann syndrome results in severe neurological impairments, while other imprinting disorders are thought to contribute to autism and epilepsy. Even in adults, imprinted genes remain part of signal cascades that influence health and disease. Disorders of genomic imprinting acquired in the course of life are associated with diseases such as colon cancer, glioblastomas and Wilms tumors (pediatric kidney cancer).

The discovery of genomic imprinting and research on DNA methylation opened the door to an experimentally grounded epigenetics. Since then, thousands of researchers have passed through this door, opening up and cultivating a field that is proving to be highly fertile for biomedical research. Thanks to the pioneering work of Solter and Surani, epigenetics is now thriving as the science of molecular biological mechanisms that regulate gene expression independently of changes to their DNA sequence.

Davor Solter, a U.S. citizen born in 1941, is Director Emeritus of the Department of Developmental Biology at the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology in Freiburg, Germany, which he led from 1991 to 2006. He now lives in Bar Harbor, Maine (USA) and is Visiting Professor at Mahidol University in Bangkok, Thailand, and the University of Zagreb in Croatia. Azim Surani, a British citizen born in 1945, is Director of Germline and Epigenetics Research at the Gurdon Institute at the University of Cambridge and a Fellow of King’s College, Cambridge. https://www.gurdon.cam.ac.uk/people/azim-surani/

The Paul Ehrlich and Ludwig Darmstaedter Prize is the most prestigious medical prize in Germany. It is endowed with 120,000 euros and is traditionally awarded on Paul Ehrlich’s birthday, March 14, in Frankfurt’s Paulskirche. It honors scientists who have made outstanding contributions in the field of research represented by Paul Ehrlich, particularly in immunology, cancer research, hematology, microbiology and chemotherapy. The prize, which has been awarded since 1952, is financed by the Federal Ministry of Health, the German Association of Research-Based Pharmaceutical Companies and earmarked donations from the following companies, foundations and institutions: Else Kröner-Fresenius-Stiftung, Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH, C.H. Boehringer Sohn AG & Co KG, Biotest AG, Hans und Wolfgang Schleussner-Stiftung, Fresenius SE & Co KGaA, F. Hoffmann-LaRoche Ltd, GSK GlaxoSmithKline GmbH & Co KG, Grünenthal Group, Janssen-Cilag GmbH, Merck KGaA, Bayer AG, Georg von Holtzbrinck GmbH & Co KG, B. Metzler seel. Sohn & Co AG. The prize winners are selected by the Scientific Council of the Paul Ehrlich Foundation. A list of the members of the Scientific Council is available on the Paul Ehrlich Foundation’s website.

The Paul Ehrlich Foundation is a legally dependent foundation administered in trust by the Association of Friends and Sponsors of Goethe University. Professor Dr. Katja Becker, President of the German Research Foundation, who also appoints the elected members of the Scientific C Council and the Board of Trustees, is Honorary President of the Foundation, which was established by Hedwig Ehrlich in 1929. The Chairman of the Scientific Council of the Paul Ehrlich Foundation is Professor Dr. Thomas Boehm, Director Emeritus at the Max Planck Institute of Immunobiology and Epigenetics in Freiburg, and the Chairman of the Board of Trustees is Professor Dr. Jochen Maas. In his function as Chairman of the Association of Friends and Sponsors of Goethe University, Prof. Dr. Wilhelm Bender is also a member of the Scientific Council Trustees of the Paul Ehrlich Foundation. In this function, the President of Goethe University is also a member of the Board of Trustees.