A large painting looks from a distance to be a classic 1930s style French poster, but get closer. Closer. Much closer, and you’ll realise that it’s not painted conventionally, but made up of hundreds of thousands of tiny dots.

This is Le Chahut by Georges Seurat and is the centrepiece of an exhibition about pointillism, painting by dots.

Pointillism was one of several styles that emerged in the 30-40 years around the turn of the 19th century, upending painting entirely. Not that the painters would have called it that – they hated the term.

The idea behind it was that rather than blending, for example, blue and yellow paints on the palette to create green, they would place tiny dots on the canvas, and when you stand back, the yellow and blue dots merge to form green.

Although somewhat faded from popular consciousness today, pointillism is all around us. It’s what underpins a lot of colour printing – the use of tiny dots of the three core colours to form the thousands of colours we see when the page is held up.

The modern printer uses microscopic dots that the eye can’t see individually, but the artists revelled in showing off what they were up to – expressing the dots visibly as part of the artwork itself.

And now a large collection of dotted paintings has come to the National Gallery for an exhibition of dottiness.

Most of the exhibition draws on a collection by one remarkable woman, Helene Kröller-Müller, the daughter of a rich industrialist who spent her wealth on art, put much of it on display for the public, and just before she died, gave the whole lot to the Dutch government.

As a group collection united by technique, it’s an exhibition that wanders somewhat from portraits to landscapes to overtly political.

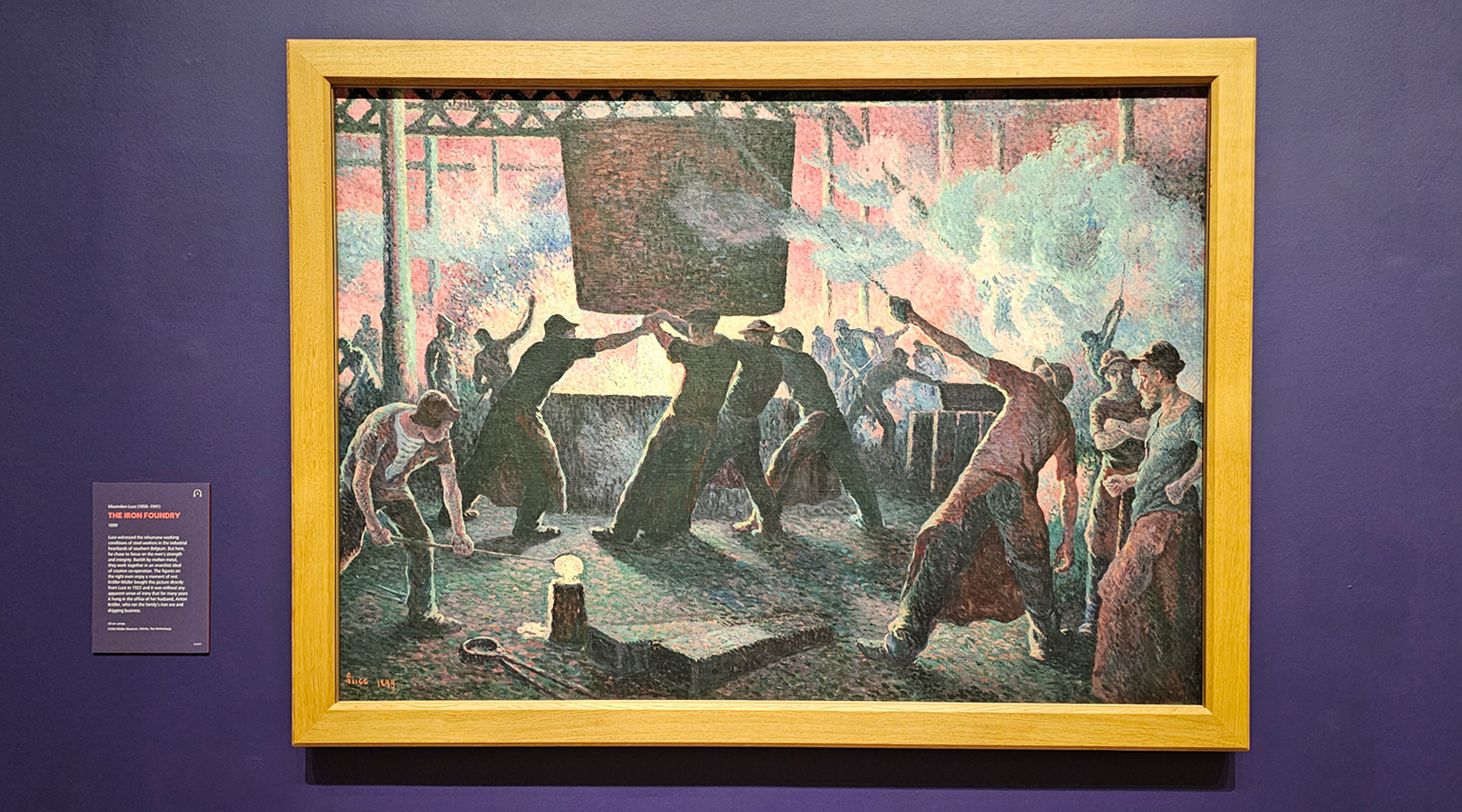

Some of the political paintings are topical, such as the before and after of a labour strike, albeit at a time when going on strike could be literally fatal. A magnificent almost Communist style painting of labourers working in an iron foundry was hung, apparently without irony, in the office of Helene’s husband, who was in charge of the family’s iron ore business.

A painting of a middle-class family at breakfast caught my attention as the man is already in a smoking jacket and hat with a stub of a cigar in his hand. Just when did he start?

Londoners may also delight in seeing several paintings of the industrial Thames.

For all the colour on display, it’s sometimes the monochrome paintings that seem most detailed, as if the colour is trying to blur things that are revealed by removing the colour.

The exhibition concludes with a transition, a woman sewing, and you can see that the semi-rigid structure of Pointillism is starting to give way to the more free-flowing Art Nouveau movement.

As an exhibition, it’s a rare chance to see some of the huge Helene Kröller-Müller collection without having to travel to the Netherlands museum, and to see Le Chahut, which hasn’t left the Netherlands at all in about 40 years.

The exhibition, Radical Harmony: Helene Kröller-Müller’s Neo-Impressionists, is at the National Gallery until early February 2026.

- Standard Ticket: £27

- Concessions: £25

- Under 18 : Free

- Art Fund : £13.50

Tickets are on sale from here.