If unemployment remains high and vacancies are falling on the quarter, why are the majority of British firms still struggling to recruit? That paradox is captured in the British Chambers of Commerce’s Quarterly Economic Survey (QES). Each quarter we ask UK businesses of all sizes and sectors if they have tried to recruit recently, and if so, have they faced any difficulties?

This historic data tells a story about the UK labour market over recent years. It is a tale of cyclical swings layered on top of stubborn structural mismatches. It reflects unprecedented upheaval following the pandemic and a reshaping of the immigration landscape. It can help us understand why British firms in 2025 still cannot find the workers they need.

From “tight” to “tighter”: 2017–2022

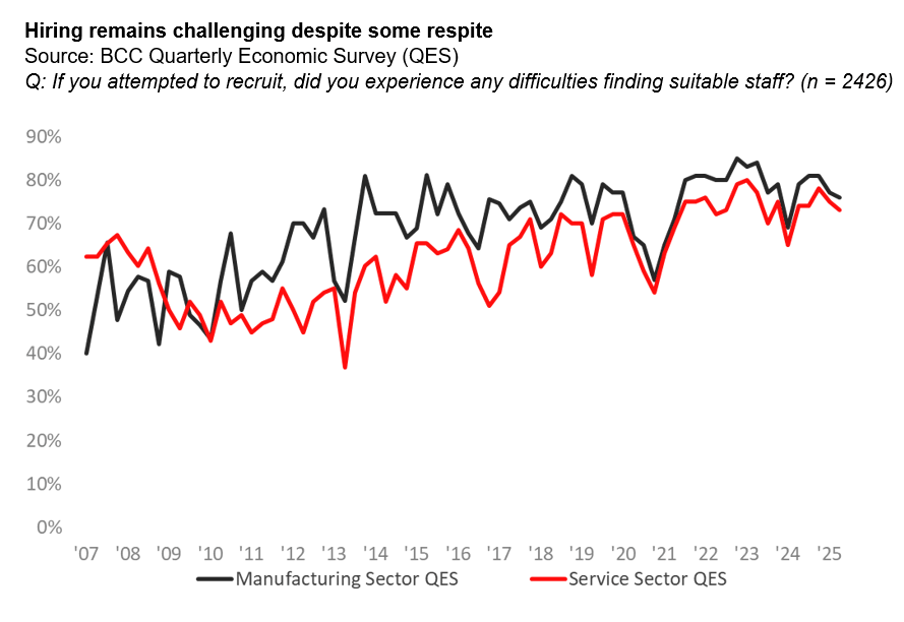

Recruitment was already difficult for many firms before the pandemic. The BCC’s survey in the late 2010s routinely showed more than half of hiring employers struggling to fill roles. But when the global economy began to reopen after 2020, the challenge turned into a crisis. By 2021, around 70% of firms that tried to hire reported difficulties, with hospitality and manufacturing hit hardest.

That figure rose even further through 2022. By the final quarter of that year, 82% of recruiting firms said they could not find the staff they needed, the highest share on record since the series began.

Chart 1: Recruitment Difficulties (% of hiring firms)

A plateau of pain: 2023–2024

The pressure stopped intensifying after that peak, but it did not ease. Across 2023, roughly three-quarters of firms continued to report difficulties, with construction and logistics particularly affected.

For a brief moment in early 2024, it looked as though the logjam might be clearing, but by mid-2024, the figure had climbed back up, reminding employers that this was not a temporary blip but an entrenched trend.

Stuck in the seventies: 2025

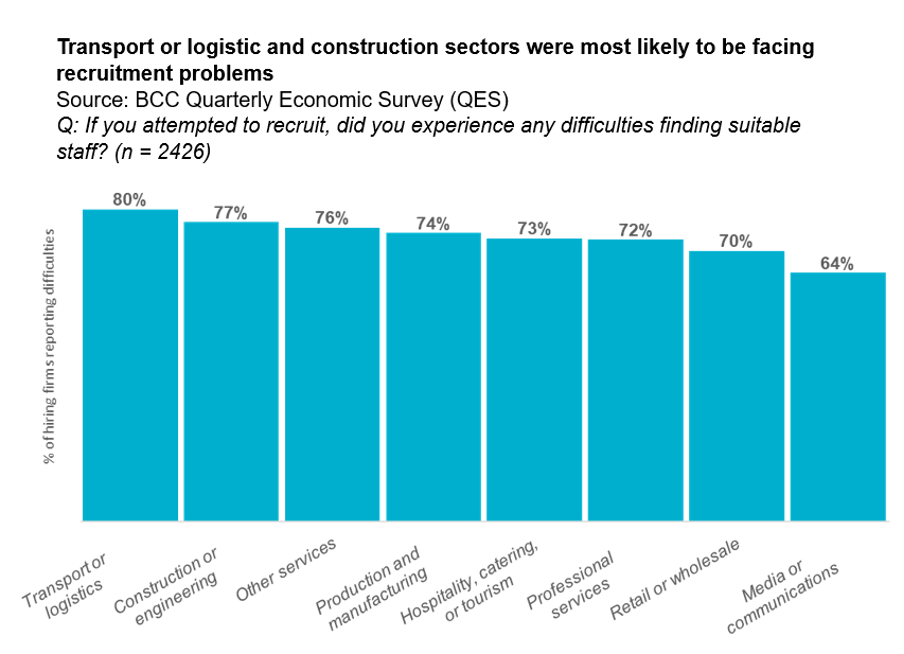

Fast-forward to 2025, and the numbers are stubbornly high. In Q1, 76% of recruiting firms still faced difficulties; in Q2, it eased only slightly to 73%. Crucially, only around half of firms (55%) were even attempting to recruit at that point, reflecting weaker demand and rising employment costs.

The pain is not spread evenly. Logistics stands out, with four-fifths of firms in this sector struggling to hire.

Chart 2: Recruitment Difficulties by Sector (Q2 2025)

Brexit and the immigration constraint

The UK’s formal exit from the EU in 2020 reshaped labour supply. The end of free movement reduced the flow of EU workers into sectors heavily reliant on them, such as hospitality, agriculture, construction, and care. Employers adjusted at first by drawing on domestic labour and global migration routes, but by 2023–24 the picture changed again.

Tighter rules introduced in 2023 raised minimum salary thresholds and increased visa fees, particularly for shortage sectors. As business groups noted at the time, this pushed up recruitment costs while leaving many vacancies hard to fill.

Deeper frictions and data doubts

The Resolution Foundation has described the post-pandemic rush to recruit as a collective scramble, colliding with reduced a labour supply. Even as vacancies cool and official surveys show labour-market slack returning, many employers remain unable to fill roles.

NIESR’s analysis supports this view. Their 2025 Outlook emphasise that recruitment bottlenecks persist despite rising unemployment. That suggests the problem is not simply cyclical overheating but a deeper mismatch between workers and jobs.

The official labour market data is also a major source of complication. The ONS Labour Force Survey, the backbone of UK jobs statistics, has been plagued by falling response rates and sharp revisions. The Resolution Foundation has flagged that official LFS estimates sometimes paint a looser picture than alternative datasets, making it harder for policymakers to read the true state of the market.

What next?

The BCC’s trend line since 2017 tells us three things. Recruitment difficulties are the rule, not the exception. Softer economic conditions may dent demand but do little to resolve mismatches. Genuine relief requires action: improving skills pipelines, recognising overseas qualifications more quickly, investing in productivity so firms can pay more, and designing migration rules that reflect real shortages.

The most concrete fact here is simple: in mid-2025, three out of four British firms that try to hire still cannot find the workers they need. That is not the mark of a healthy labour market, nor a recipe for long-term growth.