As a child of the internet, I know how much I would have hated guidelines like this. I also know how badly they’re needed.

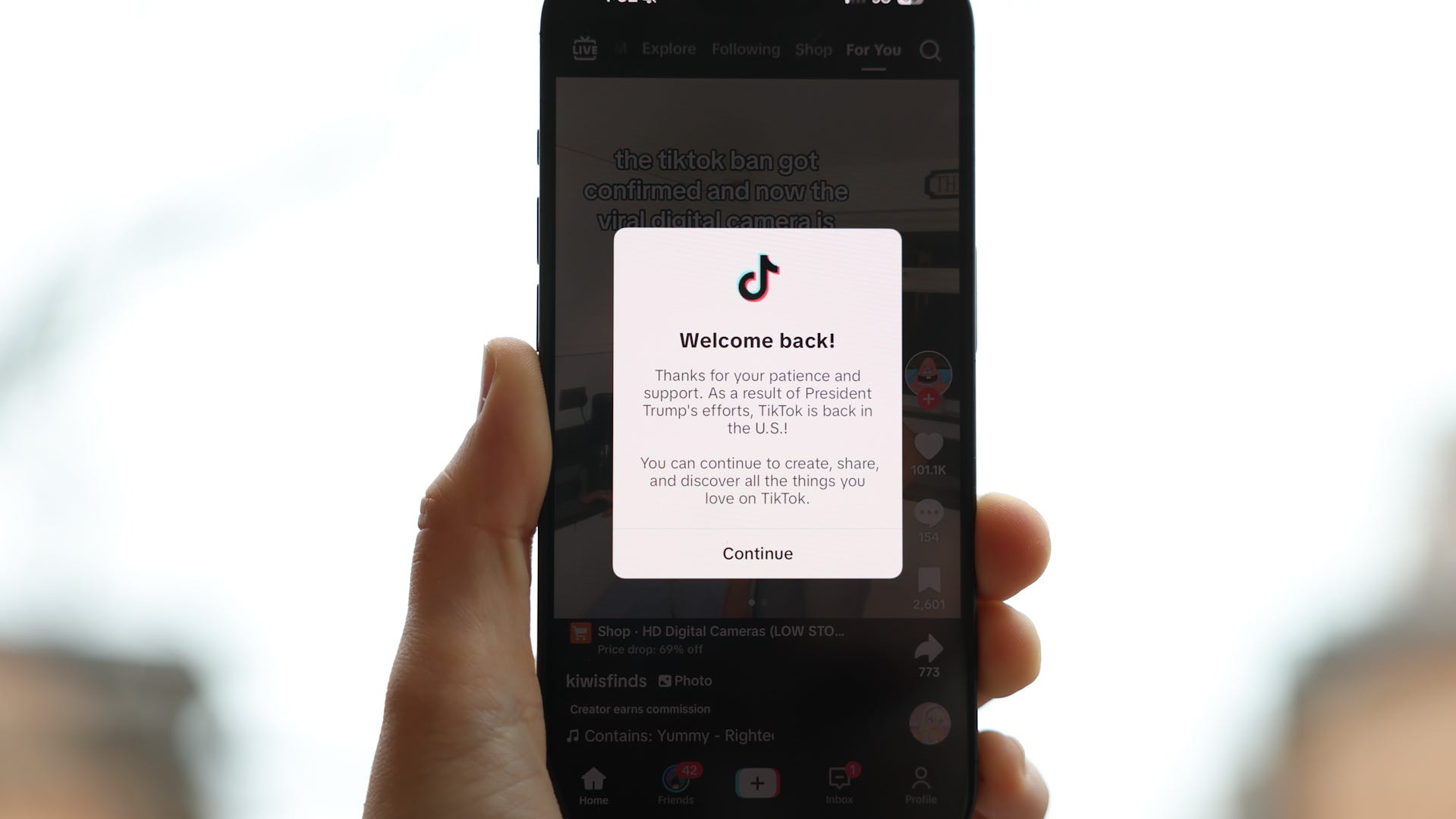

President Trump extends TikTok deadline as algorithm questions loom

President Donald Trump pushed TikTok’s ban to December 16. A U.S. buyer may be coming—but what happens to the algorithm?

On Sept. 15, New York State Attorney General Letitia James announced proposed regulations for TikTok, Instagram and other social media companies that would require some form of age verification on sites for users under 18. Although it seems that the attorney general’s office is underestimating how easy it is to skirt social media rules, it’s certainly a step in the right direction.

“The proposed rules released by my office today will help us tackle the youth mental health crisis and make social media safer for kids and families,” James said in a news release.

The new guidelines were introduced so that social media companies will be compliant with the Stop Addictive Feeds Exploitation (SAFE) for Kids Act. The new law, which passed in 2024 and has yet to go into effect, will keep children from receiving personalized feeds and notifications between midnight and 6 a.m. unless they receive parental consent.

I grew up very online. I worry for the next generation.

I have spent most of my life logged in to some social media platform or another. While I’ll never know what my teenage years would have been like offline, I am almost certain I would have had better mental health had I not been glued to a screen, capable of seeing every single thought that my classmates had and saying whatever came to mind.

I was allowed to create my first Facebook account at 11 years old when I transferred to a new school. I was hooked from the start – it felt like the place all the grownups were. Being there, I concluded, meant I was a grownup, too.

Opinion alerts: Get columns from your favorite columnists + expert analysis on top issues, delivered straight to your device through the USA TODAY app. Don’t have the app? Download it for free from your app store.

It wasn’t long before I spent all my free time on the website. I “became a fan” of dozens of pointless pages. I tended to my crops on FarmVille. I fretted about which overedited photo to use as my profile picture. I participated in a trend where teenagers would post “truth is,” prompting other people to like your status so that you could post what you really thought about them on their profile.

Even as a preteen, I knew that having the perfect online presence was part of the social hierarchy of middle and high school. I would message boys at my school with the hopes that one of them would develop a crush on me. I would try to talk up the popular girls so that they would let me into their circle. Every like, comment and tag became a source of gratification – especially if the “right people” were the ones interacting.

I got older, and my preferred platforms changed. Soon, I was posting selfies on Instagram and divulging my secrets on Tumblr. I began spending even more time online as I chased internet fame, scrolling for hours into the early morning. I also started to notice that my baseline mood was sadness. At 17, I was diagnosed with depression.

New York’s regulations are good, but implementation will be difficult

While my mental illness was not caused by my social media use, it certainly didn’t help things. I knew even then that the huge feelings swirling in my brain were exacerbated by my screen time, but I couldn’t stop scrolling.

Today’s teenagers have even more to worry about. Social media algorithms have only grown more sophisticated, to the point that every popular platform is tailored precisely to a user’s interests and habits. Artificial intelligence has become commonplace on multiple platforms, leading to a Pandora’s box of ethical dilemmas. Not to mention the content that is easily accessible online, something that was on display when the video of Charlie Kirk being assassinated went viral on X.

The regulations New York wants to implement are not perfect – I’m not even sure they’re going to work. Verifying young people via government-issued identification only works if they have a form of ID, which most people don’t have until they’re at least 15. There’s also the possibility that social media companies will confirm a person’s age by having them submit a selfie or video and analyzing it, which seems like it could be easily manipulated or just flat-out incorrect.

In spite of these concerns, I’m glad New York is trying to do something about children’s social media consumption. As a child of the internet, I know how much I would have hated guidelines like this. I also know how badly they’re needed.

Follow USA TODAY columnist Sara Pequeño on X, formerly Twitter: @sara__pequeno