Once ranked fourth on a list of the 100 most powerful people in British culture, Sir Antony Gormley continues to attract such praise as “the U.K.’s best-known contemporary sculptor” and even “world’s best sculptor.”

To account for such admiration, it helps to understand his work is characterized by a distinctive combination of qualities. For one, because most of his more than 60 large-scale public sculptures are grounded in the human figure, they remain intuitively accessible to a broad public. His 177-foot hilltop Angel of the North, for example, has a claimed audience of 33 million people per year, mainly from drivers who pass by it on a busy highway in England.

At the same time, Gormley, 75, relentlessly experiments and explores different ways of representing bodily experience, which results in challenging, experimental works that garner respect from a sophisticated art-world audience. In his first major U.S. museum survey, curated by the Nasher Sculpture Center’s Jed Morse, both these aspects of Gormley’s work are evident.

Before visiting the Nasher, I had wondered how it would handle the inherent challenge of conveying a sense of Gormley’s vast, grand oeuvre to viewers within a finite indoor space. I found the two-part installation in the Nasher’s lower-level gallery (which technically concludes the exhibition) offers an incredible sense of how the artist’s mind works, and will surely encourage visitors to look up some of Gormley’s magnificent public works, and perhaps even visit them. (To name only a few of these, I’ll mention Horizon Field, Another Place and Havmann as examples of how he engages his monumental figures with the surrounding landscape.)

News Roundups

The Nasher Sculpture Center’s lower-level gallery features several dozen scale models of Antony Gormley’s public sculptures.

Kevin Todora / Nasher Sculpture Center

The first element of the lower-level gallery is a kind of labyrinth, with several dozen scale models of Gormley’s public sculptures placed on work tables (with human figures alongside each for scale), allowing for a kind of studio tour and the ability to compare different ideas and to see how they develop.

Surrounding these work tables is the gallery’s second element: a single glass display case running around three sides of the room, containing selections from 50 years’ worth of Gormley’s notebooks, showing his stray thoughts and sketches at every stage of the process. Together these two displays provide an excellent grounding from which to see the main part of the exhibition upstairs.

In a press tour ahead of the opening, Gormley said his concern is above all with how the body experiences the space around it (as opposed to, say, the detached perspective of a disembodied eye looking upon its subject from a distance).

This concern comes from his spiritual biography, which has led him to emphasize the unity of the material body and the immaterial spirit. Raised Catholic, Gormley spent 1971 to 1974 studying Buddhism in India and Sri Lanka, and he seriously considered becoming a Buddhist monk. He credits several of his insights to Buddhist Vipassana meditation.

“Drift VI,” in the Nasher Sculpture Center’s entrance gallery is artist Antony Gormley’s take on a core human figure surrounded by a “bubble matrix” of interlocking metal shafts, as if diagramming the vectors of force that press inward and outward where the body’s surface meets the surrounding air.

Kevin Todora / Nasher Sculpture Center

This background helps make sense of the pieces that don’t look like humans, for example Drift VI, in the entrance gallery, which, Gormley says, surrounds a core human figure with a “bubble matrix” of interlocking metal shafts, as if diagramming the vectors of force that press inward and outward where the body’s surface meets the surrounding air.

Antony Gormley’s “Domain XCVI” allows for reflections of the sun, clouds and weather to penetrate the figure’s boundaries.

Kevin Todora / Nasher Sculpture Center

More identifiably humanoid, but similarly porous, the Domain series, perched on the roofs of the Nasher and those of surrounding buildings, allows for reflections of the sun, clouds and weather to penetrate each figure’s boundaries, recalling Gormley’s monumental Quantum Cloud and Exposure.

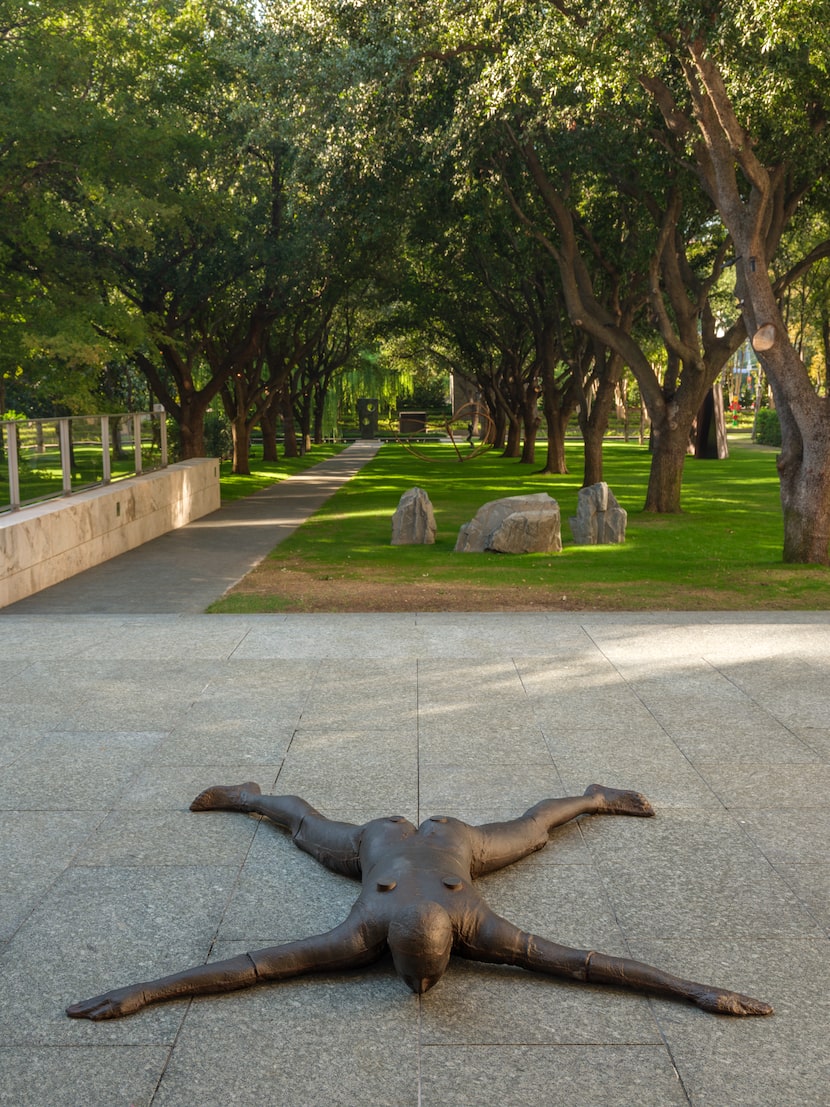

In contrast, the iron and lead casts of Gormley’s so-called body-case works, whose shapes were developed by wrapping the artist’s body with plaster as he meditated and held his posture for several hours at a time, appear more solid and connect more directly to the tradition of modern cast sculpture.

Several modern classics from the Nasher’s collection, including Rodin’s The Age of Bronze (c. 1876), are on view alongside Gormley’s works to facilitate comparison. The technique of casting calls attention to both the piece’s tactile surface and its weight, which Gormley’s casts, including Close V, Field, Prop and Three Places, exploit in various ways.

“Close V” is among the works featured in “Survey: Antony Gormley” at the Nasher Sculpture Center.

Kevin Todora / Nasher Sculpture Center

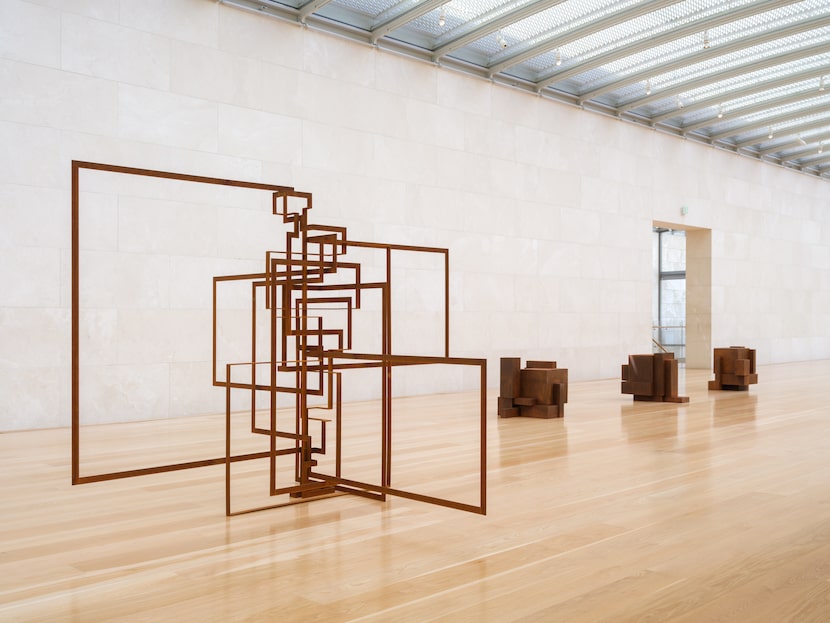

Gormley’s other main approach is to express the human body in terms of a three-dimensional architectural-type grid, using either hollow, open forms (Implicate IV and Open Hold) or closed, solid blocks (Shift, Sense and the Block series). These could be interpreted as a process moving in either direction, whether as a whole form dissolving into a collection of smaller parts (toward entropy) or as a group of smaller parts coalescing into a larger whole (toward order).

Thinking about Gormley’s work in relation to the present, and to recent popular sculptures by Kristen Visbal and Thomas J. Price, one might say Gormley belongs to a skeptical, anti-heroic trend in his avoidance of commemorating specific figures (in contrast to the typical pre-modern sculptural monument that depicts a military man on horseback, glorifying his conquests).

Some of Antony Gormley’s sculptures express the human body in terms of a three-dimensional architectural-type grid, like “Implicate IV” (left), or closed, solid blocks.

Kevin Todora / Nasher Sculpture Center

But compared to those other figurative sculptors, Gormley goes further in de-emphasizing personal identity. The human figures in his work are largely devoid of any signs of particular character or biography, being made up of only the most fundamental elements: surface, weight, sight, touch and force. Offering a sense of absence and silence, they project a meditative calm in turbulent times.

Texas mural of Charlie Kirk defaced with conservative activist’s own words

Texas mural of Charlie Kirk defaced with conservative activist’s own words

A colorful mural appeared on the side of an Edinburg grocery store. Shortly after, it was vandalized.

5 POC-owned North Texas galleries you’ll want to visit

5 POC-owned North Texas galleries you’ll want to visit

Explore art spaces that amplify underserved voices and reimage what community and creativity look like in D-FW.

Review: Fort Worth art show draws from collection of H-E-B chairman, Charles Butt

Review: Fort Worth art show draws from collection of H-E-B chairman, Charles Butt

From seascapes to abstractions, ‘American Modernism’ at the Amon Carter Museum explores a century of U.S. art and identity.

Details

“Survey: Antony Gormley” continues through Jan. 4 at the Nasher Sculpture Center, 2001 Flora St., Dallas. $10 for adults, $8 for DART riders, $7 for seniors, $5 for educators and students with ID, and free for children under 12, military and first responders with ID, SNAP EBT card holders, and members. Free every first Saturday of the month, from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., and every third Saturday of the month through October, from 6 p.m. to midnight. Open Wednesday through Sunday from 11 a.m. to 5 p.m. For more information, call 214-242-5100 or visit nashersculpturecenter.org.