The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) met last week to review part of the agency’s vaccine schedule. The independent panel considered proposed changes to recommendations for the measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella (MMRV) vaccine; hepatitis B vaccine; and COVID vaccine.

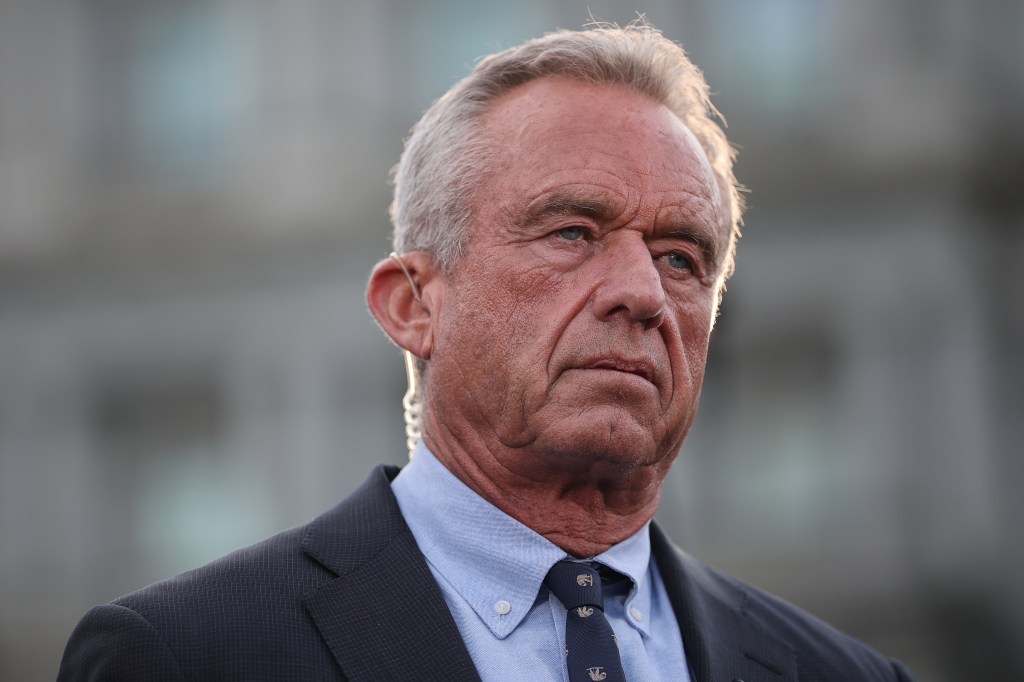

For years, hundreds of laws and regulations across virtually every state and several U.S. territories have incorporated the recommendations of the panel. But Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. overhauled the panel in June and stocked it with like-minded vaccine skeptics, prompting medical associations and states to begin unwinding their reliance ACIP guidance.

The Thursday-Friday meeting—the second since Kennedy took the unprecedented step of firing all 17 previous ACIP members and the first since he added five additional members just days earlier—further splintered the previous consensus about who should get what vaccines, and when.

Lawmakers, medical associations, and former public health officials had feared that the re-made committee would narrow or remove recommendations for some vaccines at the meeting last week, not on the basis of new scientific findings or data, but in furtherance of the secretary’s anti-vaccine agenda. Indeed, the recently fired CDC Director Susan Monarez testified before Congress last week that Kennedy had asked her to commit to rubber-stamping whatever the committee decided regardless of the scientific evidence.

The results of the meeting were a mixed bag. ACIP tabled a planned vote to recommend delaying the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine from birth to at least 1 month of age if the mother tests negative for the disease. But the committee rescinded its recommendation for the combination MMRV vaccine for children under age 4. The recommendation for a two-shot series of a separate MMR vaccine and chickenpox (varicella) vaccine for young children remained unchanged.

The panel also revoked the recommendation encouraging routine COVID vaccination and replaced it with language recommending that individuals 6 months and older consult with health care providers, a practice known as shared clinical decision-making (SCDM), about COVID immunization.

What’s the difference? As the CDC explains on its site, a routine recommendation’s guidance is that “the default decision should be to vaccinate the patient based on age group or other indication, unless contraindicated. For shared clinical decision-making recommendations, there is no default.” A member of ACIP’s COVID work group noted during the meeting that under SCDM, “vaccination is often interpreted as optional.”

The panel split 6-6 on a separate vote to require a prescription to get a COVID vaccine; the committee’s chair, Martin Kulldorff, broke the tie by voting no. Some members appeared unaware of how a prescription requirement would impact vaccine access. Kulldorff also said during the meeting that the committee doesn’t have the authority to establish a prescription requirement.

The shift in recommendations stops short of removing the vaccine from the schedule entirely, and HHS has said in a statement that insurers would continue to cover vaccination. But in the immediate aftermath of the meeting, it is unclear exactly how the new guidance will affect vaccine access. Multiple committee members themselves voiced confusion on what their votes actually meant for healthy people and for vulnerable populations trying to get vaccinated. How the panel’s changes affect access to vaccines will vary by location and how state laws integrate ACIP recommendations.

A further complicating factor is that the Food and Drug Administration’s approvals for the latest COVID vaccines, issued in August, are narrower than the new ACIP guidance, limiting approved eligibility to people over 65 or those with risky underlying conditions. The FDA’s limits have already made it harder for many people to get a vaccine without an “off-label” prescription from a doctor. The diverging and unclear guidance had already resulted in widespread confusion among state governments and pharmacies trying to preserve access and led to even people within the eligible groups being unable to get the vaccine.

Public health experts expressed relief that infant access to the hepatitis B immunization was unchanged and that the recommendation for the MMR and varicella vaccines was not rolled back even if the option of the MMRV combo shot is now set to be removed from the schedule.

“It’s kind of like low intensity, what they did in some ways. … [O]nly 15 percent of kids took the combo,” Demetre Daskalakis, the former director of the CDC’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, said in an interview with the Atlantic Friday.

“It’s more the principle, that they—with no data, with no reason to do it—have just removed a vaccine from the pediatric schedule.”

Indeed, the two-day meeting in Atlanta highlighted how successful Kennedy has been in supplanting scientific decision-making and evidence-based evaluation with rote vaccine skepticism. Many of the panel members’ statements and presentations suggest ACIP will continue on a trajectory away from consensus and data-driven vaccine analysis and toward a vaccine-skeptical agenda marked by increased confusion and polarization.

Kulldorff, an epidemiologist who has served as a paid expert witness in litigation against vaccine manufacturers, opened the meeting by laying down a gauntlet to the committee’s critics. “When there are different scientific views, only trust scientists who are willing to engage with and publicly debate the scientists with other views,” he said. “With such debates, you can weigh and determine the scientific reasoning by each side, but without it, you cannot properly judge their arguments.” He cited an op-ed authored by nine former CDC directors criticizing Kennedy and ACIP, challenging them to a public debate: “If they want to be trusted, they should accept.”

Broad vaccine policy or public health goals are topics appropriate for an open debate setting. But evaluating highly technical and scientifically complex studies and safety data is not an exercise well-suited to the debating stage, but rather, a structured, collaborative discussion where different perspectives and questions can be explored on a foundation of validated and accepted evidence—something the ACIP and its working groups were previously known for and had formalized through its evidence-to-recommendation framework.

After Kennedy remade ACIP in June, the panel abandoned that process, including much of the public transparency that came with it. The details of the proposed changes the committee would be voting on, for example, were not announced publicly before the meeting last week began—in fact, CDC staff preparing materials for the meeting apparently didn’t know the specifics of some proposals until the night before.

Several committee liaisons representing outside medical groups during the meeting asked why ACIP is considering new recommendations for these vaccines in the first place. Prior to Kennedy’s installment at HHS, ACIP would schedule votes on changes to recommendations when new circumstances (e.g., a public health emergency or a new vaccine) or new data and studies arose that prompted reconsideration. The process for developing a potential new recommendation or change to an existing one would often take the better part of a year.

The absence of that process was clear throughout the meeting but particularly when it came to the proposal to push the hepatitis B vaccine birth dose for infants back to 1 month of age. Members seeming to favor the change did not offer new safety evidence justifying the shift nor did they make clear why 1 month was selected. “Why would we pick 1 month, why [not] 2 months?” asked Cody Meissner, a vaccine expert and pediatrician who’s also the only current ACIP member who has served on the panel before. “There is no evidence that it’s safer at a later time.”

“There’s no evidence of harm from administering the neonatal vaccine that I’ve heard presented or that I’m aware of,” he added.

“Is there really a reason that the committee can provide for making a change?” pressed Flor Muñoz, a pediatrician and ACIP liaison representing the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

Later in the meeting, committee member Robert Malone addressed the query. “I think the question in my mind is a little disingenuous,” he said. “The signal that is prompting this is not one of safety, it’s one of trust. It’s one of parents being uncomfortable with this medical procedure being performed at birth.”

Malone added that “hopefully, [parents] are comforted by the data that have been provided, but I suspect that many concerns will linger.” He also noted that he had received no communication from anyone at CDC as to why ACIP was reviewing the hepatitis B recommendation now.

But the comments also highlighted what was on display throughout the meeting: the elevation of vaccine skepticism for skepticism’s sake, even in the face of contradictory evidence. While CDC staff presented a systematic review of data on the hepatitis B vaccine, noting strong evidence indicating its safety, Malone insisted, “The absence of data that statistically proves lack of safety does not mean that the product is safe.” Retsef Levi, a professor of operations management at MIT’s Sloan School of Management, advanced a similar line.

Infectious disease experts and former public health officials panned the members’ comments as removed from scientific reality. “You can’t prove absolute safety—that’s proving a negative,” Jake Scott, an infectious disease physician and clinical associate professor at Stanford University, argued on X in response to Malone’s comments. “We don’t have ‘absence of data.’ We have mountains of evidence. You’re demanding logical impossibilities while ignoring decades of proof.”

Tom Frieden, the CDC director during the Obama administration, noted, “There were statements that ‘concerns’ and ‘trust’ are more important than data—including by members who themselves, or whose organizations, have been primary disseminators of disinformation about vaccines.” Kennedy’s new picks seemed to be doing exactly what he has long accused the public health establishment of doing: substituting personal priors and ideology for sound science.

The committee’s discussion of COVID vaccine information also frustrated observers, as when Levi raised concerns about mRNA used in the shots lingering in the body after vaccination. Drew Weissman, the director of vaccine research at the University of Pennsylvania’s medical school and a recipient of the 2023 Nobel Prize for work that helped lead to the development of the COVID vaccines, said the claims rely on cherry-picked research and bad information. “What these people do, is that they search, they find one paper or two papers that make an outlandish claim based on bad data that hundreds or thousands or tens of thousands of other papers refute, they don’t mention everything that refutes it,” he told Stat in an interview after the meeting.

Some panel members veered into anecdotes and speculation about vaccine safety effects while committee liaisons and even other panel members emphasized the lack of data to support their colleagues’ assertions. “We’re going beyond data and turning into a discussion of speculation and a discussion of possible clinical outcomes for which we have no data,” Joseph Hibbeln, a neuroscientist who previously worked at the National Institutes of Health, said during the discussion of the hepatitis B vaccine.

And during both days, confusion among the committee members was apparent, with some uncertain of what exactly they were voting on, how the voting procedures worked, or even what effects their decisions would have on vaccine policy.

On Thursday, the panel voted to preserve access to the MMRV combo shot under the Vaccines for Children Program, which subsidizes vaccines for uninsured or underinsured families, even though the move conflicted with its previous vote to drop the recommendation for the combo shot. Committee members opened the second day of the meeting explaining that they were confused and had made the vote in error. As Kulldorff, the committee chair, prepared to reverse the vote, he praised the “enormous depth and knowledge” the panel possessed on vaccines and science but noted that nearly all of the members “are rookies” on the panel.

“There are many technical issues that we might not grasp as of yet,” he added.