Chicago Tribune visual journalist Stacey Wescott has been making pictures in and around Chicago for 26 years.

On Friday, she was assigned to document a protest outside the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement holding center in Broadview, where activists have been gathering routinely to show their opposition to the Trump administration’s surge in illegal immigration enforcement actions in the region. During the protest on Sept. 19, federal agents deployed a significant amount of a chemical agent upon protesters who were attempting to obstruct ICE workers and others at the facility.

During an ensuing melee after gas was deployed, Wescott made a photograph of former Marine Curtis Evans carrying an American flag amid a cloud of gas in the middle of the confrontation.

The photo soon appeared on the Tribune’s website as the featured image alongside a story about the skirmish and later in the Tribune’s Saturday print edition. Following its publication online, the photograph received substantial attention: thousands of people shared the shot on social media and the photo propelled the accompanying story to be a top read on the Tribune’s website two days in a row.

Following its publication, the Tribune asked Wescott to describe what happened on that Friday and how she made the photograph. Here, Wescott and on-site reporter Caroline Kubzansky reflect on what happened that morning that led to the image.

6 a.m.

Stacey Wescott: I arrived in Broadview an hour early because I had been out at 4:30 a.m. to photograph a local community patrol group that works to alert residents about ICE sightings in Elgin. When I arrived in Broadview, I could see protesters and other journalists were already there. I grabbed my gas mask and strapped it across my neck. I had both of my Canon R3s, one with a 24-70 2.8 lens and the other with a 70-200 2.8 lens.

6:13 a.m.

Wescott: The first confrontation of the day occurred when a small group of protesters sat on the ground and blocked vehicles trying to leave the ICE facility. Federal agents emerged from a gated parking lot, shot pepper balls and gas at the protesters and forcibly removed them.

7:05 a.m.

Caroline Kubzansky: It was the second Friday in a row I’d been out to the Broadview facility watching people try to obstruct ICE vehicles and agents and it had gotten physical the week before, too. But when I arrived this time, I saw how many more people were gathered on the street. I knew that agents, if they chose to use force, would need a lot more pepper balls, gas and manpower to subdue the crowd and clear a path.

8:33 a.m.

Wescott: Protesters could see a vehicle getting ready to leave and they lined up and locked arms across the sidewalk while a federal agent on the rooftop knelt into position, preparing to shoot pepper balls and gas canisters at the crowd. I put on my gas mask and stationed myself south of the driveway so I could see both the protesters and the agents from my angle.

Kubzansky: An automated recording ordering protesters to disperse was playing over the building’s loudspeakers. I was standing on the northern side of the gated driveway where most of the confrontations had previously taken place, wearing my gas mask and holding my phone in my hand. I was a few feet from Evans, who became the subject of Stacey’s photo.

8:34 a.m.

Kubzansky: As the gate opened, I could hear agents start to fire pepper balls from the roof. A white SUV drove very slowly into the crowd of people. I started to back up, thinking it would be better to take in the scene as a whole rather than get caught in the fray. I was maybe 10 feet from the center of the crowd and could see gas starting to rise around the car. Evans was much closer to the middle of the group.

Wescott: A protester closer to the agents picked up the gas canister and hurled it back at them as they surrounded him and dragged him back behind the gate. There was a lot of screaming on both sides.

Kubzansky: The next thing I saw was a man hit the ground, face-first, just outside the gate. Agents tackled him immediately, and I zeroed in on that arrest as the vehicle kept pressing through the crowd. Then I lost track of everything for a few minutes while the majority of the gas dispersed. I realized I didn’t know where Stacey was. We are taught to stay with our reporting partners in chaotic situations, and I gave myself a little kick for losing her.

Wescott: I couldn’t see whether it was the gas or the agents that moved the protesters out of the way, but the SUV eventually got through the crowd. Frustrated by not being able to see through the gas, I swung my camera forward and saw a man who was carrying an American flag walk into the huge cloud of gas. He didn’t have a mask on and didn’t react to the gas. I shot 44 frames of him in two seconds.

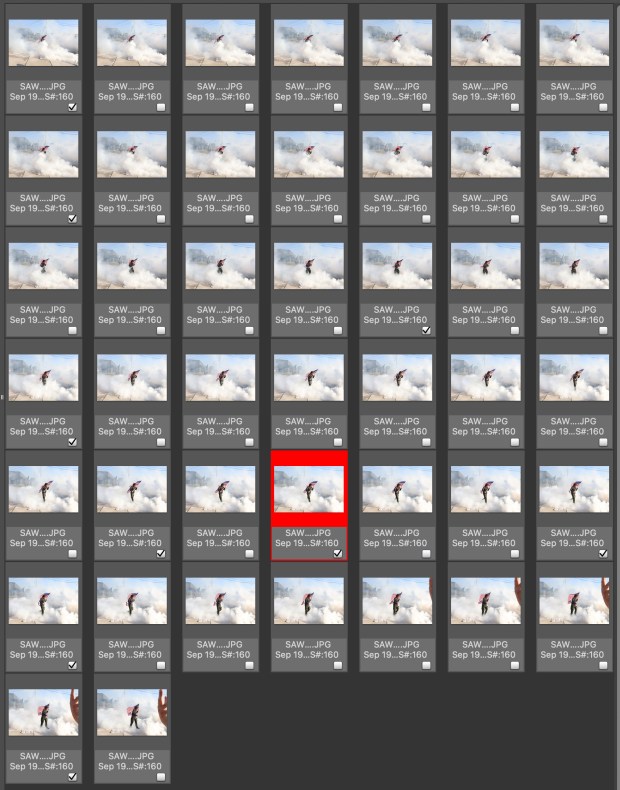

The 44 images shot by Tribune photographer Stacey Wescott showing Curtis Evans carrying a U.S. flag through gas deployed by federal officers outside of the ICE facility in Broadview last Friday morning. (Stacey Wescott/Chicago Tribune)

The 44 images shot by Tribune photographer Stacey Wescott showing Curtis Evans carrying a U.S. flag through gas deployed by federal officers outside of the ICE facility in Broadview last Friday morning. (Stacey Wescott/Chicago Tribune)

I momentarily thought, Oh, that was an unexpected moment. The white gas was lower to the ground, allowing part of his body and the flag to be visible. It was also notable because almost everyone else had fled to catch their breath, so the background was clean. People have since remarked about me including in the photo the sign on the ground that says, “Every ICE agent will be held to account.” As I took the photo, I never actually noticed it.

Shortly after taking the photos, I walked down the block to take off my mask, look through my camera, choose some photos that I thought told the story I had just witnessed and transmit them back to the Tribune’s photo desk for publication. Then I went to find Caroline. We both had gas masks on during the protest and were in decent shape, but we took turns lying on the grass, pouring water over each other’s faces.

8:53 a.m.

Wescott: I wiped off my gear and then walked back to look for the flag man.

Todd Panagopoulos, our director of photography, sent me a message: “Nice flag shot.”

I wrote back:

“Guy with flag coming thru smoke

Curtis Evans Evanston

Military veteran USMC

During Reagan

In intelligence

1980-84“

Todd knew how to decipher that and add it to the caption.

Kubzansky: I spoke to my editor about what had just happened and sent material to my colleague Rebecca Johnson, who was covering the story and writing from the Tribune’s metro desk. That’s when Stacey ran over and told me I had to come and talk to Evans. She already knew she’d made a compelling picture.

I found Evans more or less where I had last seen him, in front of the gate, with the flag still on his shoulder and a hit of pepper ball powder on one pant leg. I asked if he wouldn’t mind moving out from the middle of the driveway just in case agents released more chemicals as we were talking, and he smiled and shook his head.

“I know it’s scary,” he said.

I was struck by how upbeat and seemingly nonchalant he was about standing in front of the gate. He’s 65, lives in Evanston and said he’d recently retired from a career in public works. We talked about why he’d felt like it was important to be out there that day, his experience of the standoff with the white SUV, his history with the Marines, what he hoped to accomplish that morning and the fact that he felt himself in uncharted territory.

I end every interview by asking people if there were any questions I should have asked them. Most people initially say no but then they think of something they forgot. Evans did exactly that.

“I know what you should know,” he said. “Let people know that tear gas only hurts, and that’s what it’s designed to do. Pepper balls only hurt. You’ll be okay.”

When I saw the picture later, I thought Stacey had captured the chaos of that morning and the determination of the people there in a way that words never could.

10 a.m.

Wescott: I was told to leave, shower and edit more photos from home. I did that and transmitted 48 total photos. Nine were of Curtis and the flag, which is a lot. I asked the photo editors to review all the frames of Curtis and the flag and to select the one that best conveyed what happened in Broadview. Some photographers might cringe at this and feel strongly about choosing which one is “best,” but I didn’t feel strongly one way or the other about one particular frame.

I’ve also learned that sometimes what I think, like or feel about the photos I take isn’t always the one that resonates most with my editors and our readers. Let the editors pick, I thought. I still don’t know if they stuck with the original one published on our website or if they changed it out.

I also reached back out to Curtis to share a screenshot of the photo of him in our gallery and verify his status as a veteran — he mentioned that his Marines training included annual exposure to tear gas, where “you learn that it really sucks and it’s not going to kill you.”

After the photo was published on our website, it boomed on social media, in our newsroom and in my circle of friends and family. I am grateful that people have found such meaning in the image. Curtis shared my surprise at the reaction to the picture, and said he hopes it “galvanizes people a little.”

“The photo, just visually, was striking,” he said. “But I hope it doesn’t distract from the fact that there’s something profoundly wrong going on (in Broadview). I hope people pay attention to that fact.”

Originally Published: September 22, 2025 at 12:04 PM CDT