As several of Israel’s Western allies recognise a Palestinian state, Israel has accelerated plans for settlements that it hopes will make the two-state solution impossible.

Published Sept. 22, 2025 11:07 BST

As several of Israel’s Western allies recognise a Palestinian state, Israel has accelerated plans for settlements that it hopes will make the two-state solution impossible.

Published Sept. 22, 2025 11:07 BST

Home to 2.7 million Palestinians, the Israeli-occupied West Bank has long been at the heart of plans for a future nation existing alongside Israel. The model is known as the two-state solution to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and would also include Gaza. It is backed by most countries around the world.

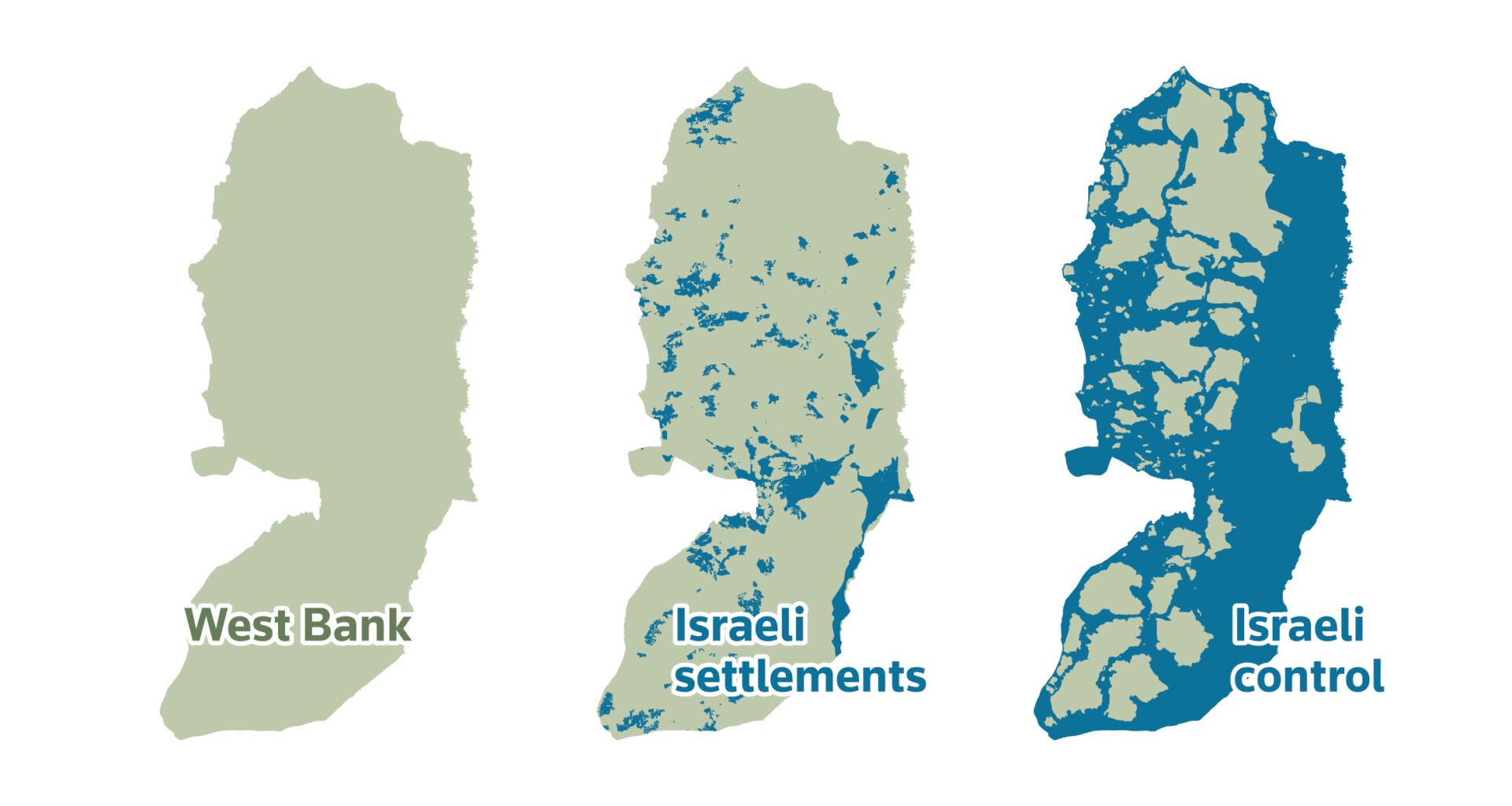

But the construction of settlements for Israelis has reduced the land left for Palestinians, cutting their towns and cities off from each other.

Approval to build settlements has accelerated rapidly under the current Israeli government, which includes vehemently pro-settler parties that want to annex the West Bank to Israel.

A Reuters review of settlement growth in the West Bank over several decades – mapping out the expansion of areas under Israeli control and exploring data showing the impact on daily life for Palestinians – reveals how deeply settlements and other measures have fragmented the territory and why, unless they are removed, an independent state seems increasingly distant.

Israel tightly restricts Palestinians’ access to land in the West Bank, carving out swathes for:

- Israeli settlements, including built-up areas, municipal areas and land cultivated by settlers

- Israeli military bases, firing zones and nature reserves

- Areas where Israel exercises civil and security control, including East Jerusalem

Part of the Israeli settlement of Maale Adumim in the Israeli-occupied West Bank, August 14, 2025. REUTERS/Ronen Zvulun

While the world’s attention has been on the war in Gaza, the situation in the West Bank may have a longer-term impact on the future of a decades-long conflict that destabilises the entire Middle East.

Western powers Australia, Britain, Canada and Portugal formally recognised a Palestinian state on September 21, a reaction to Israel’s conduct in Gaza. Most of the U.N.’s 193 member states already recognised Palestine and several others now plan to do so, a shift criticized by Israel’s staunchest ally, the United States. Netanyahu says a Palestinian state would be a security threat to Israel.

Palestinian Foreign Minister Varsen Aghabekian Shahin said the countries’ recognition was an irreversible step that brought Palestinian independence and sovereignty closer.

But it will take more than recognition to save the two-state solution.

Israeli settlements have grown in size and number since Israel captured the West Bank in a 1967 war. They stretch deep into the territory with a system of roads and other infrastructure under Israeli control, further slicing up the land.

Palestinians want their capital to be East Jerusalem, which Israel also captured in 1967, then annexed. Israel has declared Jerusalem as its own undivided capital, although only a handful of countries recognise it as such.

In July, the United Nations’ highest court said Israel’s occupation of Palestinian territories was illegal and its settlements should be quickly withdrawn, the latest call for an end to the occupation since a U.N. Security Council resolution in 1967.

There is no sign of that happening. By linking up with other Israel-controlled areas, the new settlement block approved by Netanyahu, also known as E1, would go still further, cutting the West Bank in half and severing it from East Jerusalem. Some Israeli ministers are now pressing for formal annexation of the West Bank in response to allies recognising Palestine.

A map of the area around Jerusalem, showing Israel and the West Bank. It distinguishes between Palestinian communities in green, and Israeli settlements in blue. A planned settlement named E1 is marked in a red outline. A small locator map of the West Bank appears in the lower right corner.

The E1 initiative will displace 2,500 residents of Bedouin communities from the area where the building work will go ahead, according to the Palestinian government. The largely pastoral communities say the construction of a road to the new housing will additionally cut them off from the nearby Palestinian town of Al-Eizariya, where their children go to school.

“If they build that road, it will separate us from Al-Eizariya entirely,” said Mohammad al-Jahalin, a resident of the Bedouin community of Jabal al-Baba.

Mohammad al-Jahalin, a member of a Bedouin community, looks out at an area set to be developed into the E1 project to expand the Israeli settlement of Maale Adumim, seen in the background. September 17, 2025. REUTERS/Ammar Awad

For Palestinian residents of the West Bank, the settlements not only threaten the dream of self determination after decades of Israeli occupation, but intrude on their lives in innumerable ways.

When Tareq Shihadeh, 80, looks down the hillside towards his family’s farmland from his home in the village of Ein Yabrud, he remembers a childhood harvesting olives, grazing sheep and goats and enjoying picnics by the spring.

His 17-year-old grandson Tareq has barely experienced that life. For the past 10 years armed settlers have stopped them accessing their land, shooting at Palestinians who try to walk there, Shihadeh said.

“It’s a few minutes away but we can’t reach it,” said the younger Tareq.

Tareq Shihadeh, 80, reminisces at home with his grandson about life in the Palestinian village of Ein Yabrud. July 16, 2025. REUTERS/Mohammed Torokman.

Israeli rights group B’tselem has documented incidents of settler aggression on Ein Yabrud farmers’ land, and says the neighbouring settlement of Ofra is built on land registered to Palestinians. The Yesha Council, a body that represents West Bank settlers, did not immediately reply to a request for comment.

Israel was created in 1948 through a United Nations plan to partition what had been British-controlled Mandatory Palestine. The plan gave the new Jewish state of Israel 56% of the land and an envisaged Palestinian state 43% while Jerusalem was to remain under international control.

Jewish leaders accepted the plan. Arab countries rejected it and went to war with Israel, which quickly defeated them, leaving it in control of 78% of the original territory of Mandatory Palestine. The remaining 22%, split between the West Bank, the smaller Gaza Strip and East Jerusalem, is where a Palestinian state is foreseen.

Israel captured and occupied both territories after defeating Arab armies in another war in 1967 and started building settlements soon afterwards.

It says settlements are critical to its strategic depth and security and their status should be resolved in peace negotiations, although these have been stalled since 2014.

In 2005, Israel pulled its troops and evicted its settlers from Gaza, which was later taken over by Hamas.

Palestinians and most countries regard all the settlements as illegal under international laws that prohibit settling occupied territory with an occupying power’s own population.

Israel disputes this, though it has not formally annexed the West Bank and Gaza, as it has done with East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights. Successive Israeli governments have used subsidies and other inducements to encourage Israelis to move into new settlements in the West Bank, citing historical and biblical ties to the area, which it calls Judea and Samaria

Israel’s settler communities are not homogeneous. Some settlers are driven by ideology. Others want a cheap apartment. Some settlements adjacent to Israel are seen by many Israelis as ordinary towns, unlike more isolated enclaves deep inside the West Bank.

Ideological settlers believe they are pioneers redeeming land promised by God to the Jewish people. Some have established their own “outposts” on land they have seized. These are illegal even under Israeli law, but many have ultimately been approved by the Israeli state — decisions that rights groups say encourage activists to take over more and more land.

The West Bank is now home to around 500,000 Israeli settlers. They are protected by the Israeli military and served by a network of Israeli-built roads that are often barred to their Palestinian neighbours.

Some settlements are now decades old. The largest has more than 80,000 residents. Successive Israeli governments have sworn they can never be abandoned.

The West Bank lies between Israel and Jordan.

Map showing Israel, the Gaza Strip and the West Bank with Jordan to the east and the Mediterranean Sea to the west.

The Oslo accords in 1993 were the closest Israelis and Palestinians have ever come to a peace deal. They divided the West Bank into three zones of control.

Area A Palestinian authority

Area C

Israeli military control

The same map now categorises the West Bank into Area A (Palestinian authority), Area B (Joint Israeli and Palestinian control) and Area C (Israeli military control). Gaza is controlled by Hamas and Israel is under control of the Israeli government.

The arrangement was meant to be temporary during negotiations towards a final deal but the peace process stalled.

The same map remains in view.

Israeli military barriers, settlements, bypass roads, roadblocks and jurisdictions take up land around Palestinian communities, often making it impassable to them.

The same map now highlights Israeli presence in the West Bank showing that military barriers, settlements, bypass roads, roadblocks and settlement jurisdictions weave between Palestinian areas.

Israel’s military continues to operate at will in all three zones.

The same map remains in view.

The Oslo Accords only envisaged Israeli control of Area C lasting five years, but as the peace process broke down, its control was extended and solidified.

Area C makes up about 60% of the West Bank. It often includes agricultural and grazing land belonging to Palestinian villages that are themselves in Areas A or B.

Israeli authorities exercise military law in areas they govern in the West Bank and when dealing with Palestinians detained in raids on Areas A and B. Jewish Israeli settlers are dealt with entirely under the Israeli civil code according to international rights group Human Rights Watch, which says “the application of dual bodies of law has created a reality where two people live in the same territory, but only one enjoys robust rights protection”.

Palestinians require Israeli planning permission for any development or building in Area C. Such permission is nearly always denied, the relevant Israeli authority told parliament in 2023. Israel has meanwhile designated large areas as state land, firing zones and nature reserves.

It has also allocated large parts of Area C for settlements and the infrastructure required to sustain them.

The Palestinian population in the West Bank is now largely urban, concentrated in East Jersualem and several other cities and refugee camps.

Population

density in the

West Bank

Population per 100×100m area

Population density

in the West Bank

Population per 100×100m area

Population density

in the West Bank

Population per 100×100m area

Population density

in the West Bank

Population per 100×100m area

Population density in the West Bank is visualised in a 3D spike map in orange tones, pinpointing population centres like Ramallah, Jenin, Nablus, Hebron, and Jericho. Insets show population per 100 square meters for Ramallah (45,644 people) and Hebron (244,196 people). Text explains that Israeli restrictions limit Palestinian’s access to land.

Sources: European Commission (Global Human Settlement), Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics

Settlements in the West Bank have steadily expanded over the decades. The growth is now accelerating, with the coalition governing Israel since December 2022 widely seen as the most supportive ever of settlers.

The United Nations Human Rights Council in March published a report saying Israeli settlement growth was happening at an ever-increasing rate.

Since 2023, the number of West Bank settlement housing units submitted for construction exceeded the previous nine years combined. In 2025, the number was nearly double that of 2020, the previous high in the period, data from Israeli NGO Peace Now shows.

A series of maps visualising the change in Israeli settlements within the West Bank over time. There are three maps oriented horizontally representing the years 1980, 2000, and 2024. In 1980, there was a small concentration of “Israeli settlements” marked in the upper part of the map. By 2000, these settlements appeared more dispersed. The 2024 map shows the settlements and marks “E1 planned settlement” with a red area. A more detailed depiction is presented in the inset showing Israeli settlements (blue) and Palestinian communities (green) and highlighting towns like “Nablus” and physical features such as “Highway 60”.

Many Palestinians living in the West Bank are registered as refugees with the United Nations. They or their parents or grandparents were among the 700,000 Palestinians who fled or were pushed from their homes during the fighting in 1948.

Refugee camps established in the West Bank after 1948 have grown into densely populated townships. The camps have been focal points of opposition to Israel’s occupation.

Hilltop view of the Palestinian refugee camp Balata on the edge of the West Bank city of Nablus, November 14, 2002. – REUTERS

Following the deadly October 7, 2023 attack by Palestinian Hamas militants on Israeli communities from Gaza, Israel has launched military campaigns in several camps, including in early 2025, that have displaced tens of thousands of people once more and killed hundreds of Palestinians. Israeli Defence Minister Israel Katz has said the raids reduced the threat from armed Palestinian groups.

Human Rights Watch has documented unlawful use of lethal force by Israeli security forces in the West Bank, denouncing a sharp spike in killings of West Bank Palestinians.

Palestinian fatalities in the West Bank

have risen risen after Oct. 7 attack

Palestinian fatalities in the West Bank

have risen risen after Oct. 7 attack

Palestinian fatalities in the West Bank

have risen risen after Oct. 7 attack

A bar chart displays the number of fatalities from 2008 to 2025. The vertical axis is labeled with numbers from 0 to 500, indicating the number of fatalities. The chart shows relatively low numbers from 2005 to 2020, with a noticeable peak around 2015. There is a significant increase in fatalities in 2023 and 2024, reaching close to and above 500.

Note: Data as of Sep. 11, 2025.

Source: United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs

The Israeli military also maintains control and security in the West Bank with a system of roads, checkpoints, access restrictions and gates.

Newly constructed roads to serve settlements promote the growth of settlement populations but also act as barriers between Palestinian villages.

Some highways are only open to Israeli citizens, leading to long, complex journeys for Palestinians trying to cross from one side of a restricted road to the other.

Long queues build up at checkpoints on roads that Palestinians can use. It often takes hours to travel short distances.

In early 2025 the United Nations humanitarian agency OCHA documented 850 separate obstacles to movement in the West Bank, up from 565 before the start of the Gaza war.

Add a description of the graphic for screen readers. This is invisible on the page.

A view shows Palestinian houses in the village of Ein Yabrud with the Jewish settlement of Ofra seen in the background, in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. REUTERS/Raneen Sawafta.

Settlers and Palestinians in the West Bank also have different access to resources, including water.

Daily water consumption

in the West Bank

Litres per capita per day

World Health

Organization

recommended

minimum

Palestinians

without

access to the

water grid

Daily water

consumption

in the West Bank

Litres per capita per day

World Health

Organization

recommended

minimum

Palestinians without

access to the

water grid

Daily water

consumption

in the West Bank

Litres per capita per day

World Health

Organization

recommended

minimum

Palestinians without

access to the

water grid

Add a description of the graphic for screen readers. This is invisible on the page

.

Source: OCHA and Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics.

The disparity is not only evident in household consumption, but it affects Palestinian agriculture and other economic sectors in the West Bank too.

Israeli national

water carrier

Mekorot, Israel’s national water company, dominates the pipeline

network supplying the West Bank.

Israel has imposed strict regulations on the use of the Mountain Aquifer—the main water source available to Palestinians in the West

Bank.

Access to water from the Jordan River is prohibited for Palestinians.

Israeli national

water carrier

Mekorot, Israel’s national water company, dominates the pipeline

network supplying the West Bank.

Israel has imposed strict regulations on the use of the Mountain Aquifer—the main water source available to Palestinians in the West

Bank.

Access to water from the Jordan River is prohibited for Palestinians.

Israeli national

water carrier

Mekorot, Israel’s national water company, dominates the pipeline

network supplying the West Bank.

Israel has imposed strict regulations on the use of the Mountain Aquifer—the main water source available to Palestinians in the West

Bank.

Access to water from the Jordan River is prohibited for Palestinians.

A map showing Israel and the West Bank with major water pipeline’s controlled by Mekorot, Israel’s national water company, mountain aquifers and freshwater pipelines.

Source: Mekorot, Who Profits Research Center and Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs

For Israelis living in settlements and Palestinians in adjacent villages, the different legal, security and travel rules, as well as resource access, create huge disparities. Israel says the restrictions in place protect its security.

In parts of the West Bank adjoining the border with Israel, these differences are accentuated by the barrier, a network of fences interspersed with concrete walls Israel mostly built between 2000 and 2005 in response to the second Palestinian intifada, a period of suicide bombings and shooting attacks by Palestinians, and Israeli airstrikes, demolitions, no-go zones and curfews.

The barrier runs mainly along the border, but in places it extends several kilometers into the West Bank.

An ultra-Orthodox Jew walks along part of a concrete barrier in Gilo, a Jewish settlement on land Israel captured in 1967 and annexed to its Jerusalem municipality, August 15, 2010. REUTERS/Baz Ratner

A Palestinian woman walks along a concrete barrier in the West Bank town of Abu Dis, on the edge of Jerusalem, December 27, 2005. REUTERS/Mahfouz Abu Turk

The barrier brings several major Jewish settlements in the West Bank into the Israeli side. It has also cut off some Palestinian towns and villages from the rest of the West Bank, complicating inhabitants’ ability to travel. Israel says the barrier keeps would-be Palestinian attackers from reaching its cities, however plans to extend it further have largely stalled.

Internationally-

recognized border

Barrier proposed and

under construction

Internationally-

recognized border

Barrier proposed and

under construction

Internationally-

recognized border

Barrier proposed and

under construction

A map showing part of Israel and the West Bank. The map highlights the “Barrier” in a solid line and a “Proposed barrier” in a dashed line. Areas labeled “Palestinian areas” are shaded in green, while “Settlements” are marked in blue. The barrier encircles Israeli settlements stationed between Palestinian areas.

Sources: Peace Now; United Nations OCHA occupied Palestinian territory

All of these efforts – new roads, barriers, checkpoints – have ramped up since the October 7, 2023 Hamas attack. In addition, Israel has demolished Palestinian homes including those it deems to be illegal constructions.

Attacks by activist settlers on Palestinian villages, farms and people in the West Bank have also sharply increased “in both the number and severity” since October, 2023, Israeli rights group B’Tselem has said.

Even as Israel expands its settlement building and control in the West Bank, the creation of a Palestinian state alongside Israel remains the most widely-accepted solution to the conflict both internationally and, according to Palestinian polling, among Palestinians themselves. With polls showing confidence in peaceful co-existence is low in Israel, however, settlers in the West Bank and their powerful supporters in Israel’s government are taking major strides to prevent it becoming a reality.

United Nations (Israeli settlements, restricted areas and Palestinian communities in the West Bank), European Commission (Global Human Settlement), Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics, PeaceNow, “A Survey of Palestine” prepared by the Government of Palestine for the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine in 1946

Reporting and graphics by

Angus McDowall, Ally J. Levine, Sam Hart, Prasanta Kumar Dutta, Mariano Zafra, Ali Sawafta, Charlotte Greenfield, Pesha Magid

Edmund Blair, Frank Jack Daniel, Jon McClure