In early 2020, as Luis Martinez-Sobrido geared up for his move from Rochester, New York, to Texas, he and other scientists grew increasingly concerned about reports of a new coronavirus spreading in China.

It was around early February when he arrived in San Antonio, and when the new virus went from something to keep an eye on to an impending global emergency.

Martinez-Sobrido, a molecular biologist and virologist who had spent the last two decades studying influenza, was hired by Texas Biomedical Research Institute to research a universal vaccine against the flu that would offer broad, long-lasting protection against the seasonal virus.

COVID-19 required a three-year detour from that project.

Martinez-Sobrido is widely recognized for his expertise in developing recombinant viruses, lab-produced proxies for actual viruses that are critical for developing vaccines and studying viral diseases. Texas Biomed utilized that expertise to study SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, ultimately aiding in the rapid development of the mRNA vaccines for the virus, estimated to have prevented millions of deaths and hospitalizations across the world.

Within the last two years, Martinez-Sobrido has returned to the big project he had planned when he first joined Texas Biomed: developing a flu vaccine that would offer lasting immunity against several kinds of influenza viruses — one that wouldn’t need to be updated annually.

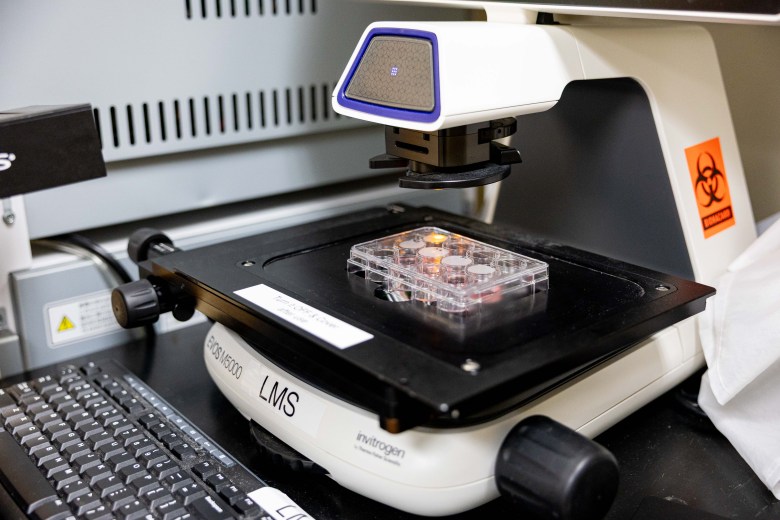

Luis Martinez-Sobrido, a molecular biologist and virologist at Texas Miomedical Research Insitute, examines cell culture plates that his graduate student use in their research for vaccines and immunization developments. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

Luis Martinez-Sobrido, a molecular biologist and virologist at Texas Miomedical Research Insitute, examines cell culture plates that his graduate student use in their research for vaccines and immunization developments. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

An educated guess

Influenza infects upwards of 40 million people, hospitalizes hundreds of thousands and kills tens of thousands of people every year in the U.S., according to 2011-2024 estimates by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Every year, scientists play a cat-and-mouse game with the virus. Because influenza has different strains and subtypes that continually mutate, the flu that circulates this fall will be different from the one that circulated last year. As a result, the flu shots we receive in our arms every fall are formulated differently.

Every summer ahead of flu season, which starts around October and lasts through May, a panel of experts convened by the World Health Organization meet to look at which influenza virus subtypes are circulating in the Southern Hemisphere during their flu season. They use this data to predict which ones will circulate in the Northern Hemisphere, and match our seasonal shots.

This process is a bit of an educated guess, Martinez-Sobrido explained.

“Sometimes these predictions are more accurate than others, and that’s why the vaccine is more efficient,” he said. “And sometimes the prediction is not that good, and that’s when the vaccine is not able to protect as well, because the virus circulating is not exactly the virus that they predicted and they included in the vaccine.”

The severity of each flu season is partly determined by how well this prediction matches the actual virus that circulates. But how many people get their seasonal shot, and which strains are circulating, also play significant roles in the number of infections, hospitalizations and deaths.

The SARS-CoV-2 virus is similarly prone to frequent mutation like influenza. The initial COVID-19 vaccines protected us against the original strain of the disease that came out of Wuhan, China. But new variants continually force researchers to update our vaccines, access to which has now been restricted in the U.S.

‘The virus is smarter than we are’

Several kinds of influenza viruses exist, but influenza A – and its two main subtypes, H1N1 and H3N2 — as well as influenza B, are the main culprits behind human flu infections.

The challenge for researchers like Martinez-Sobrido is to identify properties of the virus that are conserved across all of these different influenza strains and subtypes that could be used in a universal vaccine.

Martinez-Sobrido and his team use micrsocpoes like the EOS M5000 to look at cells and tissues and how visuruses interact with red and white blood cells in their research. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

Martinez-Sobrido and his team use micrsocpoes like the EOS M5000 to look at cells and tissues and how visuruses interact with red and white blood cells in their research. Credit: Amber Esparza / San Antonio Report

“If you use these types of protein sequences that are conserved between all the influenza viruses, the idea is that these vaccines contain these protein regions, then you will generate antibodies against these conserved regions, and then you will be protected against all types of influenza virus,” Martinez-Sobrido said.

Scientists have been researching a universal flu shot since 2008, with some endeavors even making it to early-stage clinical trials. Martinez-Sobrido is the first to do such research here in San Antonio, however.

The American Lung Association has put $700,000 behind Martinez-Sobrido’s research since 2023. Texas Biomed declined to give the total dollar amount behind the research.

There’s different ways to go about this in the lab, all of which Martinez-Sobrido and his team are investigating. That includes mRNA vaccines, which can be developed and updated more quickly than other kinds of vaccine technology. The rapid development of the COVID-19 vaccine was a result of that groundbreaking technology.

However, despite their safety and potential in treating a multitude of diseases, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. has fueled mistrust in mRNA vaccines. In August, Kennedy Jr. announced that the government was axing $500 million in funding to develop new mRNA vaccines to instead focus on “safer, broader vaccine platforms.”

Martinez-Sobrido said that they’re still looking into a universal influenza vaccine that utilizes the mRNA method, but that they’re considering alternatives, too.

So, how close are researchers to cracking the code? It’s hard to say.

“The major challenge is the virus always finds ways to mutate, and be able to overcome any potential trick that we do to protect us,” he said. “I think the virus is smarter than we are.”

“That being said,” he continued, “the more we invest in universal vaccine development, not only for flu but also for other viral infections, the closer we will be to get to a point where we will be able to develop a universal influenza vaccine.”