by Mike Koshmrl, WyoFile

In the coming months, thousands of elk will migrate onto the National Elk Refuge, just outside the town of Jackson, where the Jackson Elk Herd winters.

Historically, they’ve traveled long distances from summer range in places like southern Yellowstone National Park, but so-called “suburban elk” that stick nearer to Jackson to feed off hayfields and in residential subdivisions are increasing. It’s a headache for ranchers and wildlife managers that also reduces hunting opportunities and threatens the herd’s natural biodiversity. To best conserve long-range migration, wildlife managers would ideally concentrate hunting pressure on the refuge on the “suburban elk” — a task that has been nearly impossible until now.

“When they’re on the refuge and there’s thousands of elk milling around, you can’t tell just by looking at them whether they migrated eight kilometers or 80 kilometers,” said Gavin Cotterill, a quantitative disease ecologist with the U.S. Geological Survey.

New research Cotterill headed changes the equation.

“Based on this work,” he said, “we can predict where conflict-prone suburban elk [that get into livestock feed] are going to be.”

Cotterill’s study, “Elk personality and anthropogenic food subsidy: Managing conflict and migration loss,” assists wildlife managers with tools to decipher which of the 10,000 elk in the herd are migrating from where. Specifically, the research could help concentrate hunting pressure on the lowland elk that summer on ranchland and amid the trophy homes of the wealthiest Americans once they reach the National Elk Refuge. Doing so could help efforts to preserve struggling migratory elk that now take the brunt of the gunfire.

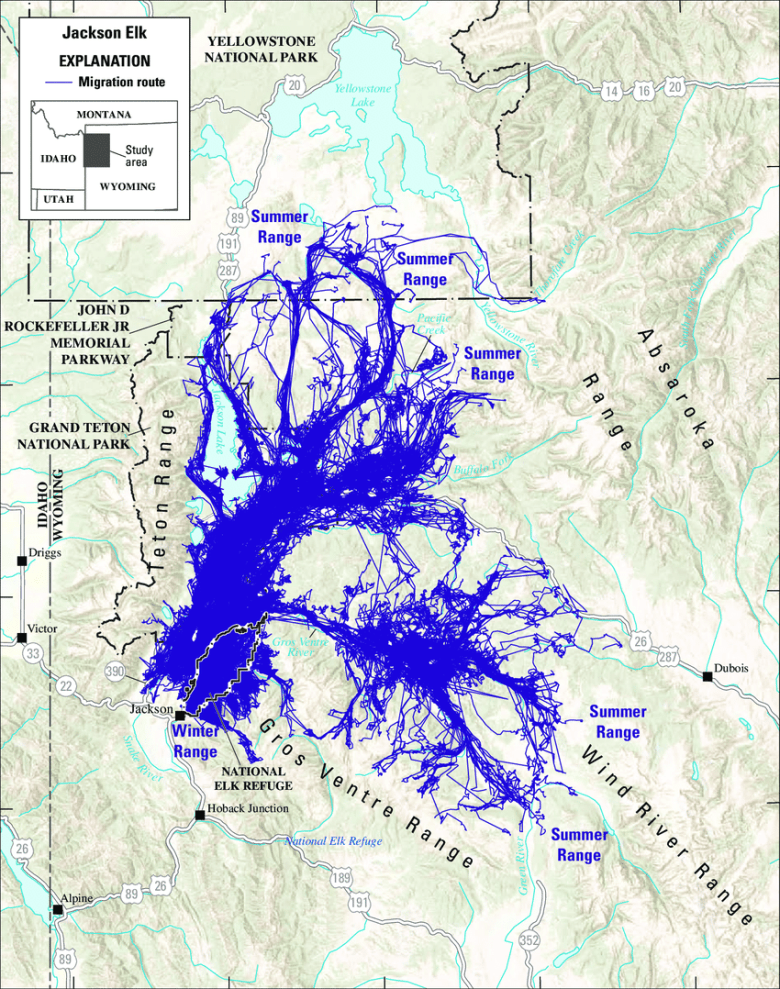

Migrating animals in the Jackson Elk Herd travel an average one-way distance of 39 miles, with journeys topping out at 168 miles. The routes are delineated in this map from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Ungulate Migrations of the Western United States, Volume 1. (USGS)

Migrating animals in the Jackson Elk Herd travel an average one-way distance of 39 miles, with journeys topping out at 168 miles. The routes are delineated in this map from the U.S. Geological Survey’s Ungulate Migrations of the Western United States, Volume 1. (USGS)

How does it work? With location data from 101 GPS-collared female elk, Cotterill used modeling to discover that the conflict-prone elk that generally live south of Grand Teton National Park were four times more likely to use the southernmost feeding areas on the refuge nearer to the town of Jackson.

“The single strongest predictor of which feeding area they’re going to use was whether they ate livestock feed in suburban areas,” Cotterill said.

That’s a finding the Wyoming Game and Fish Department has a keen interest in, and it has potential to help reverse an undesirable trend that’s long been afoot in the Jackson Elk Herd. Historically, virtually all animals that winter on the National Elk Refuge were considered “long-distance migrants” that spent summer in places like Yellowstone National Park, the Teton Wilderness, the Gros Ventre drainage and northern Grand Teton National Park. By 2012, however, the proportion was less than 60% — and the suburban elk are potentially still in the process of taking over.

“We may actually be seeing a slight increase in those short-distance migrants,” Game and Fish Disease Biologist Ben Wise said.

Thousands of elk hoofprints dot a snowy slope in November 2022 at the National Elk Refuge, where part of the 10,000-strong Jackson Elk Herd has made its annual migration. (Angus M. Thuermer, Jr./WyoFile)

Thousands of elk hoofprints dot a snowy slope in November 2022 at the National Elk Refuge, where part of the 10,000-strong Jackson Elk Herd has made its annual migration. (Angus M. Thuermer, Jr./WyoFile)

The growing imbalance, he said, is related to big differences in reproductive success and calf survival. Lowland elk that live in housing subdivisions and on ranches are adding 40 or 50 calves to their ranks for every 100 cows, but the calf ratio is only about 20 per 100 for migrating elk.

Wise, who’s a co-author of the study, explained that come fall of 2026, the bolder elk that dwell in the refuge’s southernmost feeding areas will have more of a target on their back. And it’ll be because of their own kind. He’s using the term “Judas elk” to describe GPS-collared animals that will assist Game and Fish in pointing hunters toward the problematic suburban elk. The tracked animals, in essence, will be attracting a source of danger — human hunters — to their herdmates.

“It’s something that’s really kind of novel for this area,” Wise said. “We have so many different elk coming from so many different summer ranges into this winter range [on the refuge]. And we’re definitely trying to manage for certain segments and bolster those populations where we can, while still getting harvest on the segments that we don’t have a lot of access to anywhere else.”

Easing hunting pressure on the long-distance migratory elk has historically proven a great challenge because the herds cut through other late-season hunt areas, like Grand Teton National Park. Then they’re the first to arrive at the federal wildlife refuge, where hunters are waiting for them.

Jackson Hole’s pesky suburban elk, meanwhile, spend most of the fall in a much trickier landscape where they’re hard to hunt. Then they’re typically the last cohort to show up on the refuge.

A herd of at least several hundred elk on the National Elk Refuge bid farewell to the last shed hunters departing the adjacent Bridger-Teton National Forest on May 1, 2024. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

A herd of at least several hundred elk on the National Elk Refuge bid farewell to the last shed hunters departing the adjacent Bridger-Teton National Forest on May 1, 2024. (Mike Koshmrl/WyoFile)

The “Judas elk” will help wildlife managers point hunters toward the so-called suburban elk when they do arrive.

“When they cross the line, how do we get hunters to go out there?” Wise said.

The elk will be tracked this winter as part of a broader effort to equip 150 members of the Jackson Elk Herd with GPS collars. They’ll be programmed to transmit “finite, fine-scale information” about their location several times a day from November through early January, Wise said.

In wildlife management, the concept of a “Judas” animal — a nod to the Christian Bible’s apostle who betrayed Jesus— is well established. “Judas wolves” were used during the mid-1990s to capture packmates of Canadian wolves reintroduced into the Northern Rockies, and “Judas lake trout” have also been used to map out the nonnative species’ spawning beds in Yellowstone Lake with the intent of choking out the next generation before it begins.

Using “Judas elk” to help hunters go after Jackson Hole’s conflict-prone suburban elk comes after years of effort to rebalance the herd by conserving the long-distance migrants.

“Elk are pretty, pretty savvy to anything that we’ve done,” Wise said. “How do we outsmart this herd of elk for more than just one year?”

Cotterill’s study also reflected on the complex task of conserving the Jackson Elk Herd’s migrations. Movement corridors in Jackson Hole cut through protected landscapes like the Bridger-Teton National Forest and are “pretty well preserved” as open spaces, he said.

“What we’re saying is that might not be enough,” Cotterill said.

Adaptable species like elk readily capitalize on human-related food sources, like hay meant for cattle. They also take “anthropogenic refuge” from predation, and have less risk of being eaten by grizzly bears or wolves in the suburbs than they do in wilder places.

“That’s working against long-distance migration,” Cotterill said, “in the favor of these short-distance migrants.”

Cotterill’s study was supported by the USGS’ Ecosystems Mission Area. It’s a division of the federal agency that the Trump administration is seeking to almost completely eliminate.

This article was originally published by WyoFile and is republished here with permission. WyoFile is an independent nonprofit news organization focused on Wyoming people, places and policy.

Related