Central and South Texas are hotspots for a rare parasitic disease garnering national attention as researchers argue that the disease should be considered endemic in the U.S.

Chagas disease is a parasitic disease caused by infected kissing bugs, penny-sized insects named after their tendency to bite people and animals around the mouth. Although most people don’t have long-term complications from the disease, in rare cases, Chagas disease can cause gastrointestinal problems and cardiac issues resulting in strokes or fatal heart arrythmias.

Earlier this month, researchers — including those with Texas A&M University and the Texas Department of State Health Services — laid out the case for classifying Chagas disease as endemic, which means that it spreads regularly in a given area, across the U.S. in a paper in the journal of Emerging Infectious Diseases.

The paper relied on data collected in Texas, where Chagas disease has already been considered endemic since 2013.

The disease is incredibly rare, though researchers worry that it’s also underreported, partly because it’s not labeled as endemic in the U.S. From 2013-2023, there were 273 cases of Chagas disease in Texas, according to data from the Texas Department of Health and Human Services.

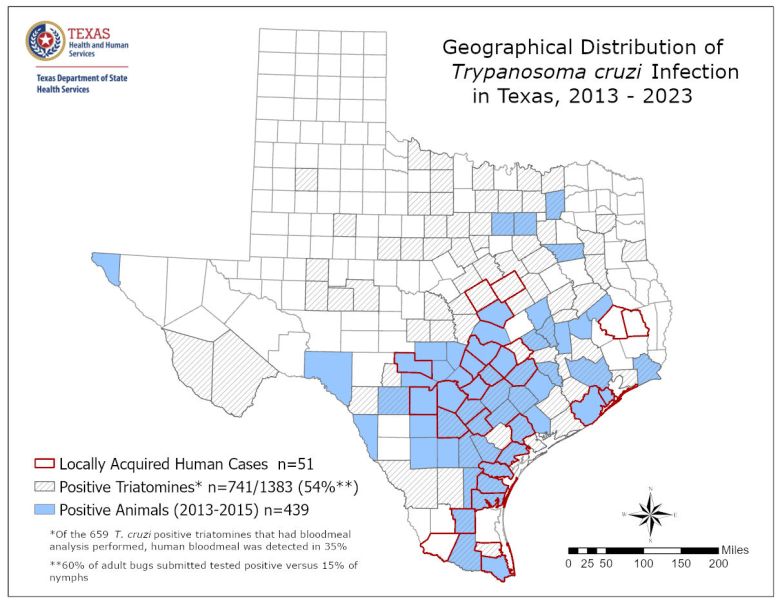

However, just 51 of those were acquired locally, the rest were transmitted in Latin America and South America, where the bug and disease are more common.

A map shows which Texas counties have seen cases of locally-acquired Chagas disease from 2013 through 2023, as well as counties where kissing bugs have been found to carry the parasite that causes the disease. Credit: Courtesy / Texas Department of State Health Services

A map shows which Texas counties have seen cases of locally-acquired Chagas disease from 2013 through 2023, as well as counties where kissing bugs have been found to carry the parasite that causes the disease. Credit: Courtesy / Texas Department of State Health Services

Chagas disease was once thought to be a disease Americans could only contract overseas, but researchers pointed to cases of locally acquired Chagas disease in eight states, most notably Texas, and the presence of kissing bugs in 32 states.

Bexar County had the most locally acquired cases in the state of Texas during that 2013 to 2023 time period, with 11. Eighty-nine of the state cases were of unknown origin, meaning it’s unclear if they were acquired locally or from overseas.

Chagas disease is even more of a concern for canines, especially wherever there are larger populations of dogs in outdoor kennels. Texas is the only state where Chagas disease is a reportable condition for canines. Available data shows that from 2013 to 2015, 431 dogs in Texas tested positive for Chagas disease.

Researchers hope that changing the non-endemic label would increase awareness of the relatively little-known disease, open up further research opportunities, better treatment, and spur efforts to monitor kissing bug populations. Gabe Hamer, a Texas A&M wildlife biologist and co-author of the paper, said that the non-endemic label perpetuates a lack of awareness and misconception that the disease can’t be acquired locally among doctors, veterinarians and the public.

“People hear the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention], they hear the World Health Organization saying that Chagas is not endemic,” he said. “They spread this knowledge that, ‘yeah the kissing bugs are here, but there’s no risk of getting exposed locally.’ But clearly that’s not the case.”

What are kissing bugs?

Triatomines, nicknamed kissing bugs or vampire bugs, are penny- to quarter-sized flying insects found throughout the Americas, as far north as Pennsylvania. They can be identified by their orange stripes, skinny legs and cone-shaped heads.

The life cycle of Triatoma gerstaeckeri, a species of kissing bug native to Central and South Texas. Credit: Courtesy / Gabe Hamer, wildlife biologist at Texas A&M

The life cycle of Triatoma gerstaeckeri, a species of kissing bug native to Central and South Texas. Credit: Courtesy / Gabe Hamer, wildlife biologist at Texas A&M

The parasite, known as Trypanosoma cruzi, can be present in about half of these bugs — with higher or lower prevalence depending on the species.

The bugs favor rural areas, often living in wood piles, rock crevices and junk piles. The presence of rodents and canines, animals the bugs feed on, will also attract them. You can find them “wherever a rat is going to be nesting, or a raccoon or an armadillo,” Hamer said.

People who live in very rural areas, or often go hunting or camping, are at a higher risk of encountering the bug. “But for the average person living more in an urban part of San Antonio, you’re not likely to encounter these things very regularly,” Hamer said.

Here’s the good, albeit gross news about kissing bugs: The method of transmission for Chagas disease from bug to humans is quite inefficient and unlikely. After kissing bugs feed on animals or humans, usually biting around the mouth and eyes, they defecate. Researchers believe that the parasite can only be transferred if the person then rubs the feces into the bite, or introduces it into the body through their eye or mouth.

“It’s just a low probability of actually happening,” Hamer said, “and that’s that’s very different from, say, a mosquito that can transmit things like West Nile Virus or Dengue [fever]. You’d have to have almost 2,000 [or] 4,000 positive kissing bugs feeding on a human before transition occurs one time, before that person actually gets exposed.”

Canines face a greater risk because they sometimes eat the bugs, a much more efficient way for the parasite to enter its host.

What is Chagas disease?

Dr. Duane Hospenthal, an infectious disease expert with the Baptist Health System, is a part of the U.S. Chagas Disease Provider Network. Even so, he only sees a handful of cases of Chagas disease every year, and people rarely come to him with major complications.

People almost always find out they have Chagas disease when they go donate blood, he said. “It’s not one of those diseases that rolls into the hospital, we diagnose and we treat right then and there,” Hospenthal said. “I would guess, if a case of this disease rolled into the hospital in most places in the U.S., it would never be diagnosed, and the patient would probably be fine.”

During the acute phase of Chagas disease, one to two weeks after being exposed to the parasite, people can experience mild, often flu-like symptoms. Another sign of a Chagas disease is swelling of the eyelid, indicating that the parasite has entered through the eye.

If not treated, the disease transitions into a chronic phase where most people don’t have any symptoms — the parasite is still present, but not causing any complications.

But about 20 to 30% of people who don’t get treatment and enter the chronic phase can have heart complications down the road, which can be fatal, as well as gastrointestinal tract problems. Hospenthal refers many of his patients to Dr. Armistead Wellford, a cardiologist with Baptist Health, who can see if the parasite is causing cardiac issues.

“Most of the time the disease is self-limiting,” Wellford said. “I really don’t have anyone who’s had any major issues with Chagas.”

That being said, Wellford encourages treatment as early as possible, often pushing patients to take a 60-to-90 day course of anti-parasitic medication, which can be challenging.

There are two medications available: benznidazole, a 60-day treatment, and nifurtimox, a 90-day treatment. Both medications have some not-so-pleasant side effects like stomach pain, rashes, headache, vomiting, and others. But Wellford tries to persuade patients that it’s not worth risking long-term risk of heart disease.

“Half of the people I have stopped it because of side effects, and they’re like … ‘I don’t have any symptoms. The medicine’s making me sick, I stopped it,’” Wellford said. “Then you have a staring contest.”

Similar to humans, dogs can develop heart problems from Chagas disease, but the canines are usually asymptomatic, according to Sarah Hamer, also a wildlife biologist with Texas A&M and co-author of the research paper.

The bottom line on Chagas disease

You likely don’t need to worry about kissing bugs and Chagas disease, the experts said. As Hospenthal put it, “it’s probably not in my top 1,000 things to worry about.”

That being said, “awareness is good,” he said.

“Certainly, if your kid wakes up and you see a weird looking bug that you can’t identify, and they have a big swollen eyelid or the side of their face, that may be something you want to know about just in case your pediatrician does not.”

It’s also good to know what the bug looks like and steps you can take to limit the risk if you live in a very rural area or go hunting or camping often. According to Hamer, you can: Reduce lights outside your home, which can attract the bug; remove trash piles, wood piles or other debris that could be habitats for the bugs; and install screen doors.

You should also limit the number of rodents and other small animals like possums, raccoons and coyotes around your home, if possible. And if you’re still finding the bug in or around your household, hire a pest control company to spray your home and seal openings where the bugs could be entering the house.

And if you find a bug you suspect is a kissing bug, you can send a photo to Texas A&M’s Kissing Bugs and Chagas Disease community science program. If it is a kissing bug, you can even send it to the university for them to test of the parasite is present.

Hamer hopes that the researchers’ paper will open up more research and funding toward understanding Chagas disease and surveillance of kissing bugs.

“In vet schools, medical schools, a lot of them already talk about Chagas, and a lot of them do recognize that it’s locally acquired, but a lot of them don’t,” he said. “And so [it would help] if it was just more across the board, helping to make sure that all practicing veterinarians, physicians or even other public health professionals to make sure they’re aware of it.”