The most striking thing about The Athletic’s interview with Jurgen Klopp this week was just how at ease he seems with not being a manager anymore.

“Not. At. All,” he responded when asked if he was fully across the previous weekend’s football, going on to extol the virtues of spending time with his grandkids, going to the cinema and attending weddings.

“I don’t want to work as a coach anymore,” he said, while adding the caveat that he might change his mind in the future.

It was interesting reading in the aftermath of Graham Potter’s departure from West Ham United, and the question that has come up in the intervening days: What now for him?

Potter’s position is a tricky one. It’s difficult to see him getting a Premier League job next, and he might consider a Championship job as too much of a step down at this stage in his career. The most likely destination feels like a mid-range European club: a Hamburg or Club Brugge, or possibly one of the multi-club groups’ outposts; a club where the standard is still good but without the same crushing pressure that comes with an Englishman in the Premier League, where the stink of failure that now (perhaps unfairly) hangs over his head will be less pungent and will be allowed to clear a little.

But here’s an alternative suggestion for what he could do next: nothing.

Or, at least, something completely different. Because he doesn’t need to be a football manager. There are other things out there.

Perhaps he should follow the lead of Klopp, and indeed Gareth Southgate, by opting out. Klopp still has a job in the game, as overseer of the Red Bull Group, which seems to consist of giving advice here and there, watching games, assessing potential signings and then persuading those signings to, erm, sign. Aside from the fact that most fans in Germany now seem to dislike him for his association with the fizzy drinks brand, it sounds like a pretty sweet gig.

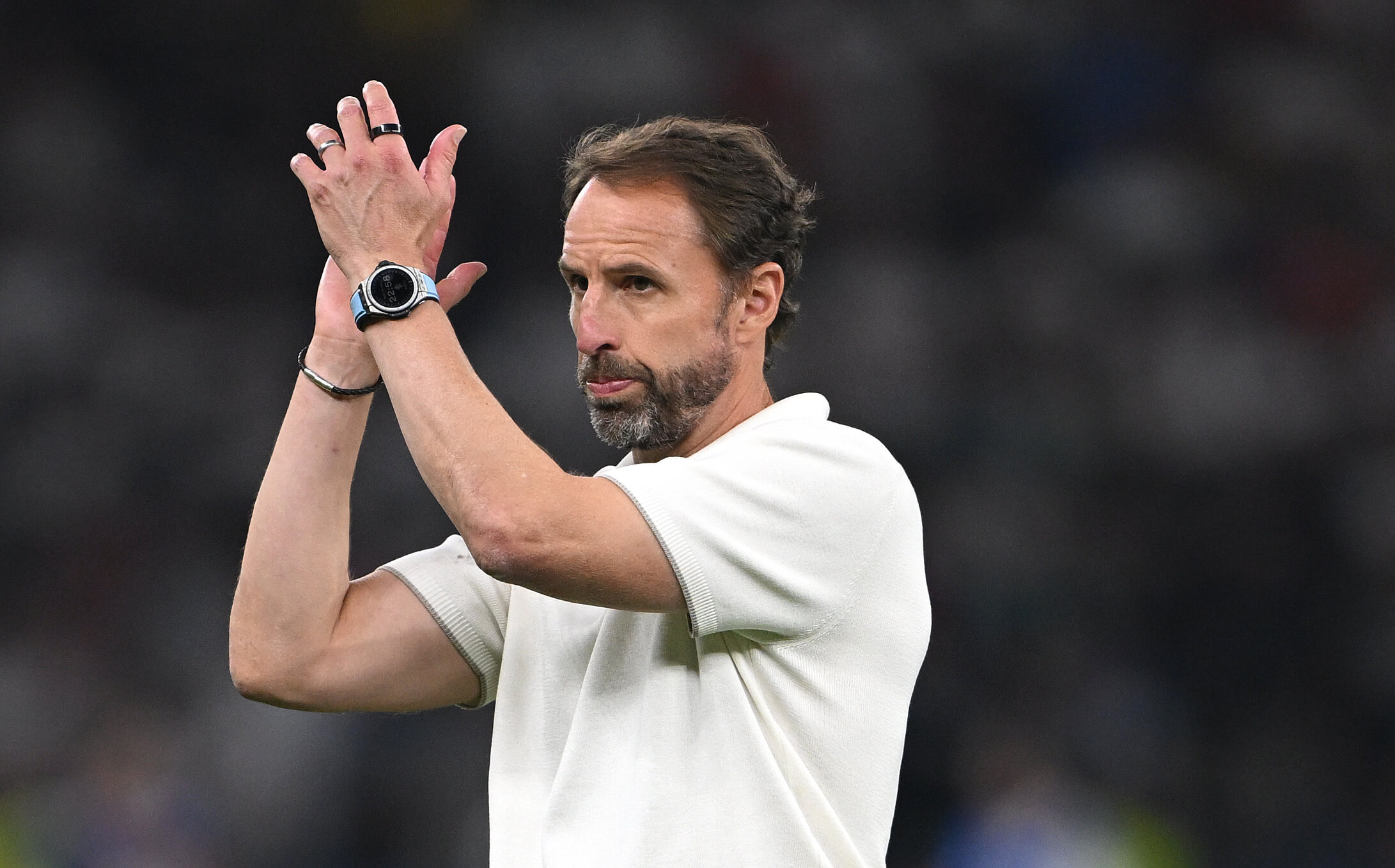

Southgate, since stepping down as England manager after a second straight European Championship final appearance in summer 2024, has floated around what might reductively be called the LinkedIn-o-sphere: giving speeches, popping up at conferences, being a guest lecturer at Harvard University, writing another book about leadership, presumably a sequel to his previous book about leadership.

Again, he seems happy. Like Klopp, Southgate said earlier this summer that he doesn’t miss the stresses of his previous employment. Last year, he told the European Club Association conference that he was “enjoying life”.

Jurgen Klopp is enjoying his role with the Red Bull Group (Rudy Carezzevoli/Getty Images)

The common factor there is a relative lack of stress. Both men are doing stuff that keeps them occupied, interests them on some level and pays the bills, but doesn’t consume their every waking thought. Sounds nice.

Granted, there is a difference between them and Potter, legacy-wise. Being sacked by Chelsea and then West Ham in less than three years is slightly different to winning league and European trophies and being a statue-level hero at three different clubs, or taking England to two major finals and making the national team likeable again. There may well be a strong sense of dissatisfaction and ‘unfinished business’ about his managerial career, which he may want to, well, finish.

But there doesn’t need to be. Potter may not have won any trophies in England, but reaching the point he did, considering his humble coaching beginnings in the Swedish fourth tier with Ostersund, unquestionably makes his career a success.

Perhaps Klopp and Southgate opting out of the coaching game, when they were surrounded by speculation about their next move and could very easily have hopped onto the first likely opportunity after leaving Liverpool and England respectively, will in some way ‘de-stigmatise’ the idea of not chasing the next job, just for the sake of it.

Southgate does not seem keen to return to management (Stu Forster/Getty Images)

There is an assumption that any manager who leaves one role will naturally just try to find the next one. Yet there’s something quite bleak about the cycle for the out-of-work manager now, in England at least: there’s the initial period of self-reflection out of the limelight; the feelers being put out to see what jobs might be available; easing back into the public eye with the odd media appearance; the interview with a trusted print journalist; the inevitable appearance on Monday Night Football, pushing around virtual counters on the big screen as Jamie Carragher nods approvingly.

Potter has already done that once, between leaving Chelsea in April 2023 and joining West Ham in January this year. The prospect of doing it all again feels exhausting for those of us watching from the outside, never mind what he must feel.

This is not intended to imply that Potter is terrible at management and thus shouldn’t do it anymore. It’s also not the same as retiring, or ‘doing an Alan Curbishley’ by drifting out of relevance to the point where the phone simply stops ringing. This would be opting out, making an active decision to do something else.

What could that be? Anything.

He could take a Klopp-esque ‘overseer’ role somewhere; he could set himself up as an advisor to other managers; he could write a book; he could give speeches; he could become a sort of roving consultant; he could start a podcast in which he discusses coaching, a more cerebral version of Sean Dyche’s Utter Nonsense; he could do something completely unconnected with football; hell, he could just roam the Earth if he wanted to. Without prying into his financial circumstances, after three Premier League contracts and nice pay-offs from two of them, it’s safe to assume he doesn’t need the money.

There would be inevitable criticism of Potter, or anyone in his position, if they chose not to pursue another job. They would be charged with a lack of ambition, of giving up, of choosing the easy path. But as a life decision, it increasingly looks like the most sensible option.

Because being a football manager increasingly seems a disproportionately stressful experience, and more difficult to control than ever before. Most are dropped into a club, usually because, at best, something has gone wrong, or at worst, due to the club being rotten to the core. They are then immediately battered from all sides by competing interests and expectations, are presented with a set of players they didn’t choose and won’t have the final say on any future recruits, and in the face of all this, are expected to get results straight away.

There’s a randomness to it which suggests there are very few definitively good and definitively bad managers, just a series of circumstances in which some people fit and some don’t, almost regardless of how skilled they are.

And what about some sort of work/life balance? What about their loved ones? When do these managers see their families and friends? Wouldn’t it be nice to think about what would be best for those closest to them? Or at least have the option of several lives other than their own not being governed by the vagaries of the football industry?

Maybe Potter still needs to be a manager. Maybe his soul is still fired by the idea of coaching, and he can’t imagine doing anything else. Maybe he is genuinely enthused by the next opportunity, whatever that might be.

But just like some of the others, he should be able to do something else, to choose another path.

How interesting and refreshing that would be.

(Top photo: Richard Pelham/Getty Images)