Shanghai Correspondent, Lianhe Zaobao

Translated by Candice Chan

China’s young graduates, adrift in a tough job market, are seeking solace in youth hostels and spiritual practices like tarot and astrology. As employment pressures mount, can new social structures offer them purpose and belonging in an uncertain future? Lianhe Zaobao correspondent Li Kang speaks to these hostel dwellers and academics to find out more about how young people are coping in a difficult environment.

Before closing her suitcase, 21-year-old Li Qian (pseudonym) carefully places her graduation certificate, degree certificate and household registration booklet on top, checking repeatedly that they do not get crumpled.

Just a few months ago, the fresh graduate had lugged all her belongings to Shanghai in search of work, staying at a youth hostel in the city centre. In mid-August, she was once again packing her things, preparing to leave.

As for what comes next, Li Qian hasn’t had time to think it through. Standing at the door of the shared eight-bed dorm room, she spoke quickly, a hint of urgency in her voice: “I’ll go home first, then see if there are any opportunities.”

As employment pressures mount, youth hostels in China’s big cities have gradually shifted from being stopovers for backpackers to temporary havens for jobseekers.

Youth hostels: temporary havens for jobseekers

The youth hostel, charging 80 RMB (US$11) for a bed per night, is the accommodation for many jobseekers like Li Qian from across China. Some move out after finding work, some settle in for a longer stay, but many more, like Li Qian, remain only briefly before quietly leaving again.

As employment pressures mount, youth hostels in China’s big cities have gradually shifted from being stopovers for backpackers to temporary havens for jobseekers. They also reflect the harsh realities faced by today’s youth. Under an increasingly severe job market, young people in China are like floating duckweed, swept along by the tide of the times — without roots to anchor them nor any shore to rely on.

Sensing this uncertainty, when 28-year-old Kun first entered the workforce two years ago, he chose to stay long term in hostels. His reasoning was simple: renting an apartment requires at least one month’s deposit plus one month’s rent, which means a stay of at least two months. In contrast, living in a hostel meant that even if he were laid off, he could pack up and leave at any time.

In July this year, Kun moved from Shenzhen to Shanghai, joining the ranks of hostel-dwelling jobseekers. On his first night, he immediately began revising his portfolio, preparing to look for a job as a designer. In Shanghai — where spending feels like “burning through Shanghai currency” — he stuck to a strict food budget of no more than 50 RMB per day. At this pace, his “reserves” could last another six months.

As for whether he could find a job within six months, Kun sounded fairly certain in his first interview: “Shanghai already has the most job opportunities of any city. If I still can’t find one despite working this hard, then I’ll just go home. There’s no point in struggling.”

From lively to quiet over past ten years

For 34-year-old hostel regular K, today’s youth hostels feel very different compared to a decade ago. He shared that people used to stay in hostels to make friends and exchange stories from all over the country. Now, with more jobseekers checking in and improved facilities, the atmosphere has become much quieter.

At the Rumianke Youth Hostel near Shanghai’s Jiangsu Road, there are four-, six- and eight-bed rooms. Each room, about 20 square metres, has a shared bathroom and shower. The bunk bed, less than two square metres, is the only private space residents have. Although many people stay together, they tacitly stagger their washing times and avoid disturbing one another.

… nearly one in five young people outside of school is unemployed.

The most popular spot in the common area is a row of individual study desks facing the wall. Every evening, these seats are filled with young people hard at work — reading, revising resumes or preparing for interviews. Each person is absorbed in their own task, and there’s hardly any conversation to be heard.

Behind this change is the intensifying pressure of job competition over the past decade. Since China’s government first released youth unemployment data in 2018, the figure has climbed from just over 10% to a record 21.3% in 2023. In December of that year, the government adjusted the calculation by excluding students still in school, which lowered the rate to below 20%.

However, according to the latest figures from China’s National Bureau of Statistics, released on 17 September, the unemployment rate for 16- to 24-year-olds not in school rose to 18.9% in August, the highest level since the statistical adjustment. In other words, nearly one in five young people outside of school is unemployed.

Nearly one in five young people outside of school is unemployed.

Nearly one in five young people outside of school is unemployed.

Facing a one-in-five risk of joblessness, even graduates from China’s top universities dare not be complacent. Lei Xi, a 20-year-old student at a prestigious university in Shanghai, moved into a youth hostel this summer to begin her third internship.

Majoring in finance, Lei Xi’s internships spanned internet companies, quantitative hedge funds and foreign firms, essentially covering the main paths she intends to pursue after graduation. Even so, she does not hide her employment anxiety, describing the current job market as “brutal, distorted and terrifying”.

She said that most of her classmates are simply trying to “get by”, giving up hopes for a job they actually like. “As long as there’s a job we can do, that’s enough.”

Lei Xi has also long understood that passion must rest on an economic foundation — otherwise, one must bow to reality. “A three- or five-year career plan is impossible. If I can be sure of what I’ll be doing next year, that’s already pretty good,” she said.

They move from the familiar spaces of hometowns and schools into strange social settings, experiencing multiple layers of disembedding — spatial, relational and professional — which brings greater and more complex pressures and uncertainties. — Zhao Litao, Senior Research Fellow, EAI, NUS

Today’s migrant youth: worse off

Zhao Litao, a senior research fellow at the East Asian Institute (EAI) of the National University of Singapore (NUS) who has long studied social stratification and mobility, told Lianhe Zaobao that in the context of major changes in the economy and employment structure, today’s Chinese youth live in an era of high uncertainty. It is difficult for them to form stable expectations or make long-term plans.

He pointed out that the root of the problem lies in a “structural reality”. The dilemmas facing young people in China are not due to their individual abilities or choices but are shaped by the broader macro environment. However, lacking social support networks, they can only manage on their own by continually adjusting their expectations and behaviours, gradually slipping into a state of “atomised disembedding”.

“Disembedding” refers to the severing of ties between individuals and their familiar social structures, leading them to drift away from their original environments and networks of relationships.

Today’s young Chinese who live in hostels while job hunting often find themselves in entirely unfamiliar cities.

Today’s young Chinese who live in hostels while job hunting often find themselves in entirely unfamiliar cities.

Zhao explained that the first generation of migrant workers who moved into big cities had the support of fellow villagers, relatives and other familiar networks. By contrast, today’s young Chinese who live in hostels while job hunting often find themselves in entirely unfamiliar cities. They move from the familiar spaces of hometowns and schools into strange social settings, experiencing multiple layers of disembedding — spatial, relational and professional — which brings greater and more complex pressures and uncertainties.

Among them, elite university graduates feel especially deprived: “They have been studying hard since childhood, only to end up unable to secure suitable jobs. The harm caused by this gap is all the more severe.” — Professor Chang Chih-chung, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Taiwan’s Kainan University

Professor Chang Chih-chung of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Taiwan’s Kainan University noted that young Chinese today are broadly facing a widening gap between their educational credentials and job expectations. Among them, elite university graduates feel especially deprived: “They have been studying hard since childhood, only to end up unable to secure suitable jobs. The harm caused by this gap is all the more severe.”

After a month in the hostel, Kun left Shanghai and returned to Shenzhen in late August. In a follow-up interview, he said that he had secured a position at a design firm there, back in a role familiar to him.

Before leaving Shanghai, Kun did not receive a single interview notice; he had only managed to complete his portfolio. When asked why he left, his reply was brief, “Shanghai’s fine too, just that I had fewer friends there than in Shenzhen.”

Preparing for ‘doomsday’

Amid unprecedented confusion and uncertainty, some young people in China have learned to prepare for the worst, as if engaged in a “doomsday survival” race against time.

When asked what skills he had prepared for “doomsday”, Kun blurted out: selling starch sausages.

This was not mere fantasy — it came from his own experience. While working in Shenzhen, Kun had set up a street stall with a friend selling hamburgers. Despite all the effort, they did not make any profit. He later realised that a simple sausage-grilling business requiring just 200 RMB in capital (100 RMB for a grill and 100 RMB for supplies) was actually the optimal solution.

A resident goes up the steps at a youth hostel.

A resident goes up the steps at a youth hostel.

Kun doesn’t shy away from his willingness as a university graduate to run a street stall. In fact, he views it as a practical choice: “By the time I turn 35, many jobs might be replaced by artificial intelligence. So I might as well try working for myself now and see if I can make it.”

Growing up in an era of dramatic economic fluctuations and rapid technological change, this generation seems almost naturally trained to cope with the ebb and flow of fortunes. Kun calmly added, “When the tide goes out, you’ll see who’s been swimming naked.”

Nowadays, more and more of her peers also turn to mystical practices, from Western tarot, star charts, and divination, to Eastern fortune-telling, incense offerings, astrology and praying to deities.

Meanwhile, some young people place their hopes in mysticism. Li Xuehan, a 20-year-old sociology student, has been learning about bazi (lit. Eight Characters) since high school. Nowadays, more and more of her peers also turn to mystical practices, from Western tarot, star charts, and divination, to Eastern fortune-telling, incense offerings, astrology and praying to deities.

When interviewed, Li said that fortune-telling gives her a kind of “power to believe”. She shared, “If it tells me the future will be good, then I feel more faith in life, and the present suffering becomes bearable.”

She thinks that young people’s willingness to believe in mysticism has a lot to do with today’s social uncertainty. Li said, “I feel very lost about the future. I don’t know which direction to take, so I need something to guide me, to give me something to believe in.”

Authenticity and turning inward

Li was one of the interns who came to Shanghai and stayed in a hostel this summer. But by the third week of her internship, she chose to resign.

With her cropped haircut, she projects a rebellious and tough vibe. However, Li said quitting her only in-person internship during college was neither impulsive nor an act of rebellion, “I already got a sense of the headhunting industry through my internship and learned how my boss thinks — that’s enough. Besides, this is my last summer before entering the workforce. Shouldn’t I take a break?”

“Slow down, wait a little” — Li repeated this phrase several times during the interview. It reflects a personal value system she’s been rebuilding since starting university, focused on stepping away from the whirlpool of meritocracy, understanding her true needs, and “becoming a mature person”.

“We’ve already enjoyed the most abundant material life. Ours is the generation meant to develop spiritually.” — Li Xuehan, a 20-year-old sociology student

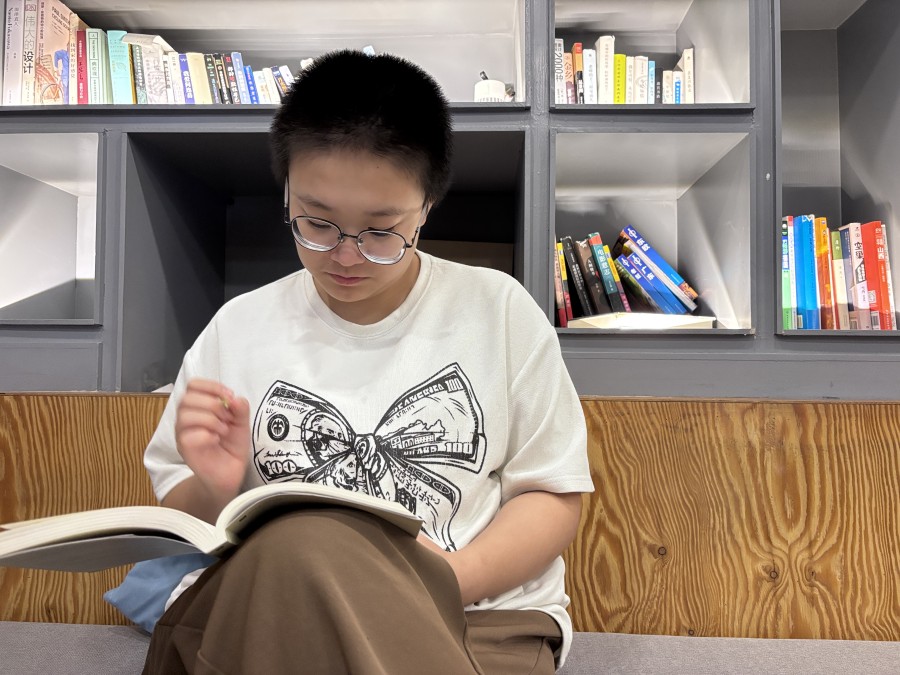

The usually bubbly Li Xuehan during a quiet moment.

The usually bubbly Li Xuehan during a quiet moment.

Her definition of maturity is: to view the world rationally, to accept her own emotions and to exist in society as an independent individual without relying on any other identity.

But how does she resolve the practical problem of supporting herself? Li admitted that finding a job that meets all her expectations is difficult, but getting one that pays is not impossible: “I’ll definitely be able to survive.”

Li said that what feels more urgent than income is spiritual growth: “We’ve already enjoyed the most abundant material life. Ours is the generation meant to develop spiritually. If we don’t take on this task now and pass it onto the next generation, then where exactly are we heading?”

Academic: society should keep up with youth

In the preface to his new book Remaking Youth: Essays in Anthropology and Sociology (《再造青年:人类学社会学论集》), published this May, Yan Yunxiang, an anthropology professor at the University of California, Los Angeles, described the growing focus of young people on their inner lives as an “inward turn”.

He wrote that in contemporary Chinese society, young people are clearly at the forefront of this inward turn, showing a strong interest in inner harmony and the pursuit of it. “The inward turn has enhanced young people’s capacity for self-reflection, prompting them to rethink and challenge the values imposed by the adult world,” Yun said.

NUS’s Zhao Litao also noted that while new social norms and values take time to develop, shifts in social and economic realities happen much sooner, forcing young people to face them first. As a result, youth mindsets often outpace broader societal changes.

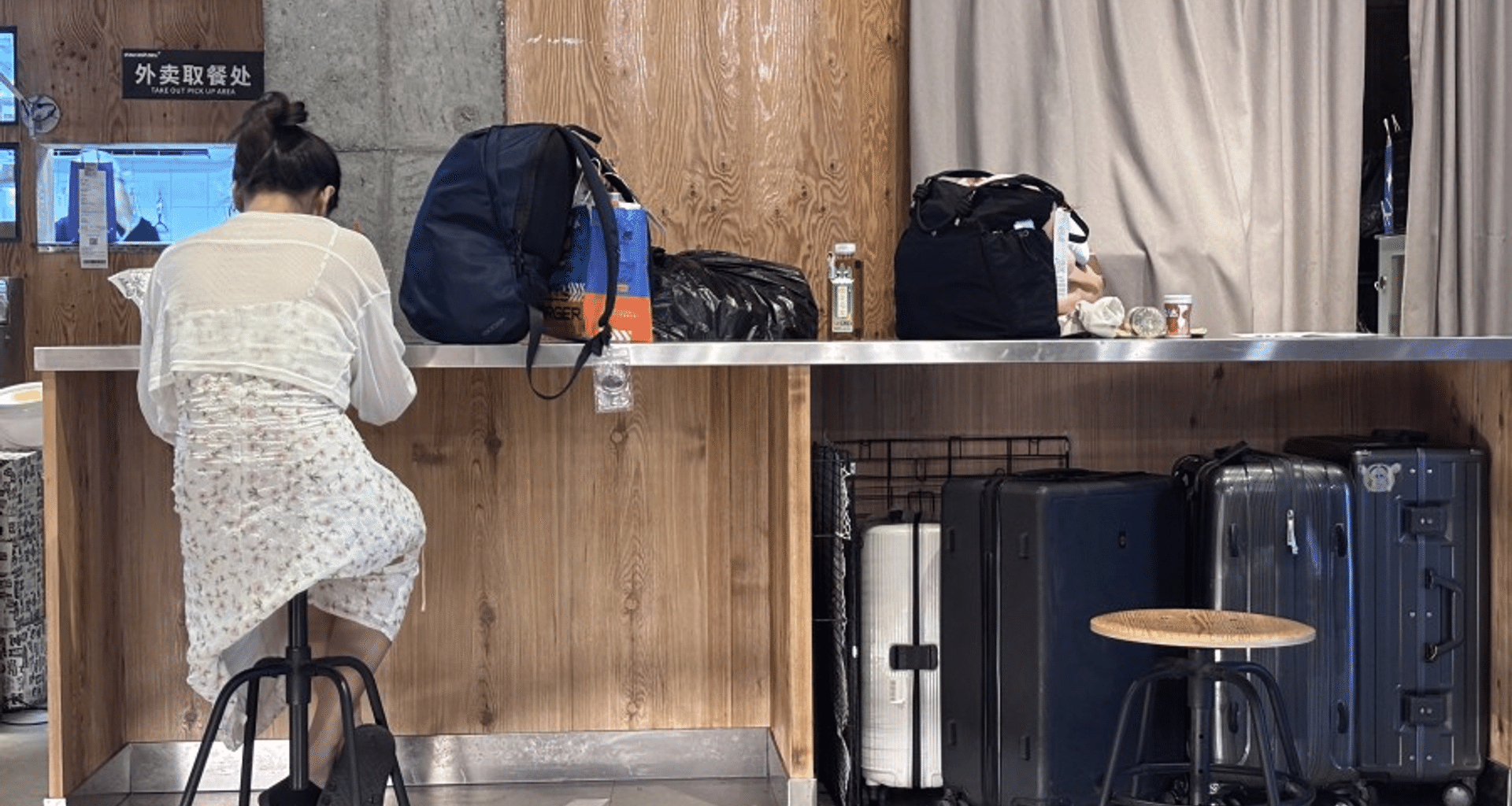

Residents at a youth hostel in Shanghai.

Residents at a youth hostel in Shanghai.

In an ideal scenario, he said, the values and support systems of society as a whole should adjust accordingly. But at present, young people face not only difficulties in finding jobs but also multiple pressures from social expectations and parents, while the support they receive remains far from adequate.

How can China’s “atomised disembedded” youth be reintegrated into society? Zhao argued that young people need not only decent jobs but also meaningful lives. Institutions, culture and norms all must adapt and evolve to create spaces where young people can find both purpose and belonging.

The government could provide more reliable and longer-term spaces for youth through employment services, transitional housing and growth resources. — Zhao

He pointed out that alumni associations, hometown fellowships and social work organisations could all play a role. Compared with youth hostels, the government could provide more reliable and longer-term spaces for youth through employment services, transitional housing and growth resources.

“Changes in social values are inevitable,” Zhao added. “What we hope for in the future is not a single fixed model, but a truly inclusive environment that embraces diverse career paths and ways of life.”