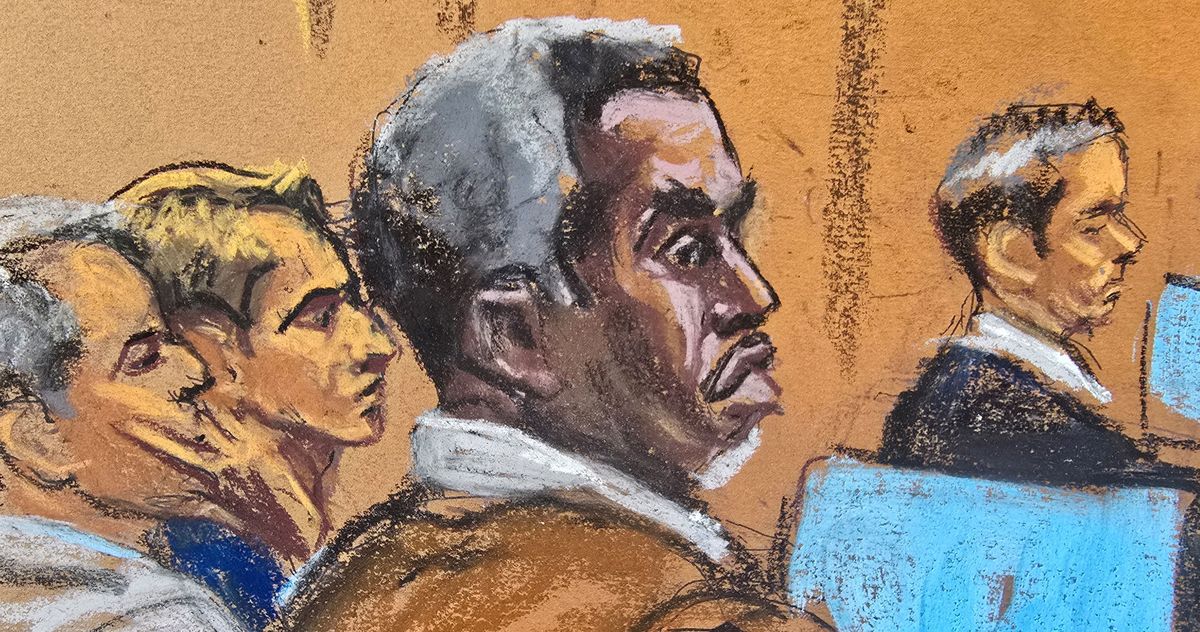

Photo: Jane Rosenberg/REUTERS

After more than six weeks of graphic and often grueling testimony, the sex-trafficking trial of Sean “Diddy” Combs is nearing its conclusion. Since proceedings opened in May, prosecutors have called more than 30 witnesses to the stand, their testimony painting a despicable picture of the mogul. His ex-girlfriend Casandra “Cassie” Ventura described a pattern of alleged physical, sexual, emotional, and financial abuse sustained throughout their 11-year relationship. Various employees recalled working for days without sleep, in one case telling the court they endured kidnapping and, in another, rape. “Jane,” a recent ex of Combs’s, said the rapper ensnared her in a cycle of coerced sex, which she was still struggling to understand. The government’s witnesses testified to bribery, extortion, drug distribution, and a suite of other crimes they claimed Combs covered up by leveraging his business networks and formidable influence in the entertainment industry. “He doesn’t take ‘no’ for an answer,” as Assistant U.S. Attorney Christy Slavik put it in her closing arguments. “The defendant used power, violence, and fear to get what he wanted.”

Combs faces five counts of racketeering, sex trafficking, and transportation to engage in prostitution, to which he has pleaded not guilty. Legal experts have cautioned from the start that this case is a tricky gambit. Because domestic violence, sexual abuse, and extortion are not federal crimes, “the Feds have taken what is essentially a lot of disparate state crimes and charged them as a federal case,” explains Sarah Krissoff, a trial attorney at Cozen O’Connor and former federal prosecutor for the Southern District of New York. “They’ve tried to do that coherently by putting it under the umbrella of racketeering and sex trafficking, but it just doesn’t fit perfectly within those frameworks.” The defense consistently sought to exploit the gaps, arguing that while Combs engaged in intimate-partner violence and drug abuse, he is not guilty of the particular crimes he has been charged with. Instead, the team said, he is a man with out-of-the-box tastes in the bedroom, which were always consensual, if also kinky.

Combs’s team did not call any witnesses of its own, a potential signal to jurors that the defense felt there was nothing to rebut and that the government failed to meet its burden of proof in the case. In his closing arguments, lead defense attorney, Marc Agnifilo, told jurors that prosecutors had taken Combs’s “swingers’” lifestyle and spun it into a “badly, badly exaggerated” tale of trafficking. “He did what he did,” Agnifilo said. “But he’s going to fight to the death to defend himself from what he didn’t do.” As jurors prepare to find that line, here’s a breakdown of the charges against Combs and the sticking points the jury may face as it deliberates beginning on Monday.

The federal government defines sex trafficking as using “force, fraud, or coercion” to get someone to participate in a commercial sex act: a scenario predicated on the exchange of sex for something of value, whether given, promised, or received. Racketeering, as defined under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, generally speaks to organized crime: A person — or, more often, a group of people — engaged in a pattern of criminal behavior in order to turn a profit. The RICO Act has historically been used to prosecute the Mafia and requires the commission of at least two “acts of racketeering”; in Combs’s case, the government says those acts include bribery, arson, kidnapping, extortion, and forced labor. Transportation to engage in prostitution, meanwhile, is exactly what it sounds like: bringing a person across state lines to engage in a commercial sex act.

While it may be a stretch to argue that Combs’s entire portfolio of businesses — his record, production, and clothing companies; his alcohol label — was a front for a system of sexual abuse, the RICO statute can still apply if legitimate business occurred alongside the alleged criminal activity. “What seems to be the biggest thing,” explains Julie Rendelman, a former Brooklyn prosecutor and current defense attorney, “is the desire to protect himself from any type of reputational and criminal exposure.” If Combs had committed crimes, and then directed his employees to commit crimes in order to bury anything that might damage his standing in the entertainment industry, that would fall under RICO. “That would include the payoffs to the hotel workers,” Rendelman notes, and “the threats to expose certain things about people who speak out.”

For former Manhattan prosecutor Jeffrey Chabrowe, however, the fact that none of Combs’s alleged accomplices has been charged “does look weird.” Chabrowe notes that RICO cases usually involve more than one defendant, often dozens of them. “The idea would be that the bigger the organization and the longer their reach — the more people he needs to run a record label and/or do everything that he’s doing with these victims — the more help he needs,” Chabrowe says. “He can’t be doing all this on his own.”

In court, several names came up repeatedly in connection with Combs’s alleged crimes. According to witness testimony, his longtime chief of staff, Kristina Khorram, helped him buy back security-camera footage — in which Combs can be seen brutally assaulting Ventura in an elevator bank — from the Intercontinental Century City hotel in Los Angeles. Khorram was also accused of encouraging Jane to fly with narcotics in her checked bag after Combs told her to bring him drugs. The rapper’s close friend and head of security, D-Roc, was said to be present for many instances of abuse and once took Ventura to a plastic surgeon after Combs split her eyebrow on a bed frame. That so many people supposedly involved in Combs’s alleged criminal enterprise have not been charged, Chabrowe says, “I think that’s going to make a jury wonder.”

For Chabrowe, the sex-trafficking charges are more straightforward. Many people might conceive of sex trafficking as the kind of crime Agnifilo described in his closing statements (“I suppose you can sex-traffic your girlfriend if you sell her into prostitution,” he said). But according to Chabrowe, it doesn’t always work that way. “You don’t have to necessarily use violence to traffic someone,” he explains. “They could be free to leave. They can have ID. They can have a phone. They could even be getting paid. But if they’re somehow being coerced, it’s still sex trafficking.”

In Ventura’s case, that manipulation is easy to spot. As a Bad Boy artist, her career was in Combs’s hands; as she and several other witnesses testified, her ability to take professional opportunities hinged on Combs’s approval. If he was upset with her, she testified, he might take away her car, confiscate her phone, or beat her so badly that she had to spend the following week recovering in a hotel. Because Combs often watched Freak Offs from the sidelines, directing and recording each encounter, he also had a lot of damaging footage at his disposal, which Ventura said he routinely used to blackmail her into cooperating. Other witness testimony backed up her claim: Ventura’s mother testified to sending Combs $20,000 after he threatened to release two sex tapes of Ventura, which a transaction email and financial records corroborate. The Intercontinental video, too, might help jurors understand the consequences Ventura faced if she didn’t comply with his wishes — particularly if they buy her claim that the beating occurred in the context of a Freak Off and that the mogul chased her down as she tried to escape.

Jane also testified to bouts of explosive violence, including one argument in which she said Combs kicked down a series of doors as she tried to hide from him, then “picked me up in a choke hold and choked me,” as Vulture reported. That alleged assault continued for hours and ended with her agreeing to a “hotel night” she did not want after Combs got in her face and asked her, “Is this coercion?” Jane insisted she deeply loved Combs and wanted a substantive, monogamous relationship with him, but she was also financially reliant on him. The mogul sent her $10,000 per month to cover her rent. “I feel obligated to perform these nights for you in fear of losing the roof over my head,” she said in a text to Combs.

The defense also showed text messages in which Jane and Ventura seemed to express consent, and even, occasionally, eagerness, when it came to Combs’s sexual fantasies. The team has returned to those messages again and again to demonstrate that whatever abuse may have occurred in these relationships, the women’s participation was voluntary. But “sex crimes can happen even in sometimes-loving, long-term relationships,” says Rendelman; for Combs to be convicted on the trafficking charges, the jury must “accept that someone can be forced to do something because of what’s hanging over their head, whether it be financial or, in Cassie’s case, fear of being physically abused.”

Although it’s certainly possible that a juror could be confused about whether Combs’s behavior was coercive or “part of the story of a really horrific relationship,” Krissoff says, they don’t need to find that the women’s participation was forced in every sex act; “you just have to find that one of them was.” That’s a point prosecutors hit in their closing arguments, reminding jurors that if there is “one single Freak Off that jurors find was the product of force, threats of force, fraud, or coercion, Mr. Combs should be found guilty of sex trafficking.”

The sheer volume of evidence and the length of the proceedings may make it difficult for panelists to keep the timeline of the case straight. “The reason the government uses the racketeering statute a lot is that you can fold up tons of disparate criminal acts into one charge,” Krissoff explains. That’s useful for prosecutors. But it’s potentially confusing for jurors because there are so many different pieces to puzzle into one picture. “Not only is it a long trial, which is hard for juries, but it’s a really sprawling presentation of evidence,” Krissoff notes.

Prosecutors’ closing arguments seem to have succeeded in simplifying the case for jurors, outlining precisely what they need to deliver a guilty verdict on each count and pointing to evidence — of drug distribution, kidnapping, and bribery, for example — that would satisfy the guidelines. Yet jurors also need to believe the government’s witnesses, and as Rendelman notes, those witnesses have some credibility issues. “Most of them had a financial stake in it,” she says. “Some of them had immunity from their own prosecutions.” The defense has repeatedly hammered home the idea that Combs is, as the team puts it in its cross-examination of Mia, the victim of a “Me Too money grab.” In his closing arguments, Agnifilo returned to that idea, describing Ventura as a “winner” who was “sitting somewhere in the world with $30 million” after settling with Combs and the Intercontinental. Jane, he pointed out, was still living “in a house [Combs is] paying for.”

The defense will be hoping for a full acquittal, though based on the transportation-to-engage-in-prostitution count alone, that outcome seems unlikely. Prosecutors presented records of Combs personally haggling over the cost of the male escorts he hired and flew over state lines. That charge carries a maximum prison sentence of ten years.

When it comes to the bigger allegations in the case, there’s a mountain of evidence jurors must parse. It’s harder to dodge a conviction once the jury develops a negative view of the defendant, as Krissoff observes, and in this case, there’s not much to like. Still, she adds, “the risk to the government here is that the defense needs only one person to agree with them.” That’s not outside the realm of possibility. Say one of the jurors has been shamed for having a kink, or for their sexuality; they might feel some sympathy for Combs, who was described on the stand as a bicurious cuck. His team has painted him as a man who is being persecuted for unconventional sexual preferences, and if it succeeds in “getting under the skin of just one person,” Krissoff says, that could trigger a hung jury and a mistrial.

On the flip side, the Intercontinental footage — which prosecutors played for jurors dozens of times throughout the trial — makes it hard to cast Combs as an empathetic figure. In Rendelman’s opinion, jurors may struggle to separate that video from the other allegations against him.“I think it’s hard for a jury to unring a bell,” she explains. “When you see the darkest side of an individual and then you hear multiple individuals discussing that individual in similar terms, it’s going to have a far-reaching impact on each of the charges — even when it arguably shouldn’t.”

If prosecutors don’t succeed in getting a conviction on the RICO count, which carries a prison term of 25 years to life, a conviction on even one of the two sex-trafficking counts would be enough to earn Combs at least 15 years in prison. According to Chabrowe, that number may rise if the judge thinks prosecutors came close to proving their RICO argument. “He could get not guilty on large parts of the case,” Chabrowe says. “But, basically, as long as he goes down on any of it, he’s getting double digits.”

Stay in touch.

Get the Cut newsletter delivered daily

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice