It’s Sunday, September 3, 1939, and the world is once again at the brink of a global conflict. Hitler’s invasion of Poland is underway, and Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain is soon to speak from 10 Downing Street. And, in A.D. Players’ production of Freud’s Last Session by Mark St. Germain, over at 20 Maresfield Gardens, London, 83-year-old Sigmund Freud awaits the arrival of a young Oxford professor named C.S. Lewis.

Though Lewis assumes Freud’s invitation is based in his taking offense at a character Lewis modeled on Freud, one Lewis describes as a “vain, ignorant old man,” Freud says no. He never read Lewis’s book; he was intrigued by Lewis’s essay on Paradise Lost.

Freud, an avowed atheist, has summoned Lewis, an atheist-turned-Christian, to understand why he “abandoned truth and embraced an insidious lie.” In turn, Freud wonders if Lewis came, at least subconsciously, for a debate. Regardless of whether or not he did, that’s what the men find, an intellectual tête-à-tête that digs not only into their different worldviews, specifically regarding the existence of God, but also their families and, in particular, their fathers (whom they both despised), the problem of suffering, sex, mortality, and humanity, which appears to be once again on the eve of catastrophe.

Though Freud and Lewis never met in real life, St. Germain was inspired to bring them together for a morning conversation in his 2010 play by Armand Nicholi, a Harvard professor who turned his course on the two men’s diametrically opposed viewpoints into a 2002 book called The Question of God. As such, the play is talky and never leaves its singular location, Freud’s London study. Though light on action, Christy Watkins’s direction keeps the evening taut, expertly navigating the ebb and flow, the wit and tension of St. Germain’s script so the back-and-forth never gets a chance to wane in the play’s brisk, 80-minute runtime.

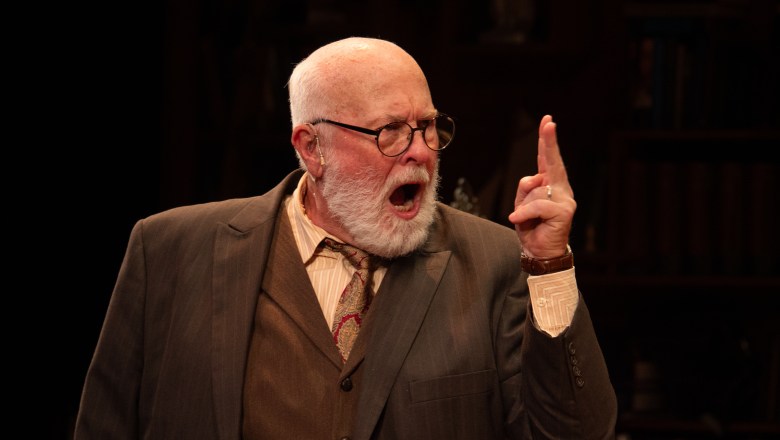

James Belcher in Freud’s Last Session at A.D. Players. Credit: Jesse GrothOlson

James Belcher in Freud’s Last Session at A.D. Players. Credit: Jesse GrothOlson

Freud’s Last Session is a two-hander, and, as such, the production belongs to its two actors, James Belcher and Philip Hays.

Belcher projects every bit of the intellectual certainty you would expect from Freud, his voice sure and booming. But it’s the way Belcher embodies Freud’s illness, with a recurring cough and a handkerchief glued to his hand, that adds tension and poignancy to the character. His cancer, inoperable and advanced, forces his own frailty to the fore, undermining him, as even though his mind is sharp and he is more than willing to bark and bellow his disagreement, his body repeatedly betrays him when he does.

Opposite Belcher, Hays plays C.S. Lewis with an openness and optimism that stops just short of naivete. His younger status is further emphasized by Costume Designer Marissa Burnsed, who gives Hays a softer look, with a light blue sweater vest beneath his jacket. Hays’ quieter mannerisms are a good foil to Belcher’s bombast. As Lewis, Hays often appears to take Freud’s more aggressive salvos in stride, with a curious tilt of his head and a thoughtful twist of his mouth. Though Freud does manage to score some direct hits, it’s the air raid siren, and the ensuing panic, that reveal an even deeper humanity in Lewis’s character. Hays lets the shadow of Lewis’s experience in the World War I settle over him – composure disappearing, eyes unseeing, breathing uneven.

Together, Belcher and Hays settle into a captivating rapport, making it easy to forget that the play is just two men talking in one room. Their chemistry is entrancing, particularly during humorous exchanges. Belcher’s quips lean dry, sometimes disdainful, while Hays delivers with more of an aware, understated amusement. The perfectly played rhythm keeps the conversation dynamic and real. The momentum of the play is further sustained by the design choices, which ensure the world hums (and sometimes wails) with life throughout the show.

Philip Hays in Freud’s Last Session at A.D. Players. Credit: Miranda Zaebst

Philip Hays in Freud’s Last Session at A.D. Players. Credit: Miranda Zaebst

The play is contained within one crescent-curved set, which depicts Freud’s London study, a replica, he says, of the one he left behind in Vienna after fleeing the Nazis. In the hands of Scenic Designer Chad Arrington, with properties by Charly Topper, the room, highly detailed and richly textured, feels like an extension of Freud’s mind – overflowing with knowledge. Books fill the shelves that line the walls and more are stacked, precarious and haphazard, in every available nook. Artifacts, busts, a globe, and other assorted knick-knacks, as well as a phone and radio that are almost third and fourth characters in the play, fill the space between.

Amongst the furniture is, of course, Freud’s famous couch, the throw over it an echo of the Qashqa’i shekarlu rug that covered the real deal. The real prize of the room, however, is the eye-catching stained-glass window at the set’s center, flanked by red curtains drawn to mostly obscure the frosty windows through which the men look for and catch glimpses of the encroaching war outside.

The war is an ever-present threat looming over Freud and Lewis’ encounter. It’s made most concrete via the updates coming in over the radio and then panic-inducing when the air raid siren blares, both diegetic examples of Sound Designer Jacob Sanchez’s contributions to the production. They interrupt and add further depth to the world outside the study.

Christina Giannelli wraps the study in warmth with her lighting choices, giving the room an almost cozy feel that contrasts with the war so close on the horizon. The 14 light bulbs that hang bare over the stage add an interesting note, again emphasizing the concept of ideas at play here. Most effective, though, is the dramatic spotlight that introduces Freud in the play’s opening image – standing before the stained-glass window, back to the audience – which the show later closes with, circling back to it in a haunting tableau.

Freud’s Last Session is a gift of an answer to the question-plea of “to be fly on the wall.” For a brief moment, over at The George Theater, you can be a fly on the wall to hear two of the finest thinkers of the 20th century engage in a little good faith debating on a Sunday morning, though it’s far from a quiet Sunday morning. War is inevitable, and life is never guaranteed. Freud says at one point, “Do you count on your tomorrows? I do not.” This sense of urgency is woven though the play, making the production not just an intellectual exercise, but a deeply human reflection on the questions that we wrestle with most. And, as Freud reminds us, the “greater madness is not to think of it at all.”

Performances of Freud’s Last Session will continue at 7:30 p.m. Wednesdays through Fridays, 2 and 7:30 p.m. Saturdays, and 2 p.m. Sundays through October 19 at The George Theater, 5420 Westheimer. For more information, call 713-526-2721 or visit adplayers.org.$30-$85.

This article appears in Jan 1 – Dec 31, 2025.

Related