By Andy McCullough, Dennis Lin and Cody Stavenhagen

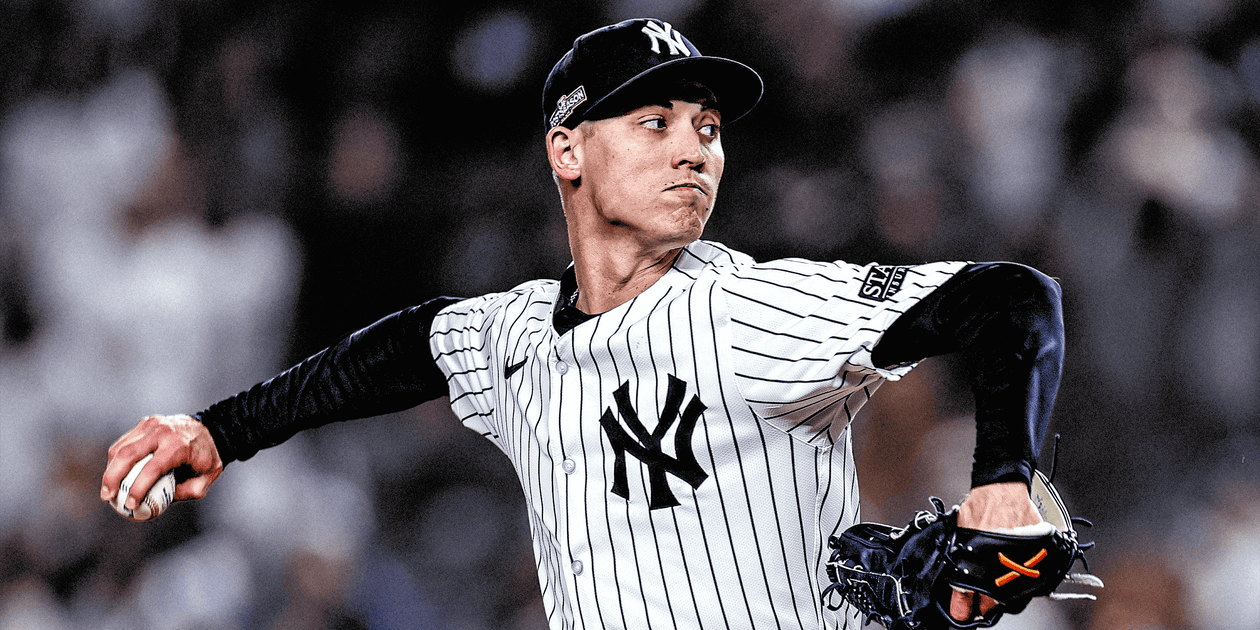

During the final weeks of the regular season, as New York Yankees reliever Luke Weaver spiraled into unreliability, he found himself confronting a time-honored baseball problem that has become more acute in the current era. He worried he was tipping his pitches.

When he took the mound, he admitted after Saturday night’s wretched outing in Game 1 of the American League Division Series, he worried “if I’m giving things away, if I’m doing things out of the ordinary that people are picking up on.” His thoughts became jumbled, which has hampered his effectiveness. And his concerns are not unfounded, Yankees pitching coach Matt Blake confirmed. In October, Blake explained, “there are more eyeballs on you.”

And what those eyeballs have increasingly been trained to do in the past few seasons is spot clues from pitchers. As the postseason continues, those within the game expect the discourse about pitch tipping to only increase. When Philadelphia Phillies reliever Matt Strahm served up a go-ahead home run to Los Angeles Dodgers outfielder Teoscar Hernández in Game 1 of a National League Division Series on Saturday, Hernández’s teammate Andy Pages had raised his right arm moments before the pitch. Was Strahm tipping? Was Pages signaling the catcher’s location? Were the Dodgers simply bluffing? Either way, the ball landed in the seats, and the subject occupies the minds of pitchers across the sport.

“It’s always something you have to be worried about,” San Diego Padres starter Dylan Cease said. “And you never really can be 100 percent sure that it’s not going on.”

Interviews with players, coaches and executives provided several reasons for the widespread paranoia. The implementation of PitchCom in 2022 has shifted scrutiny away from the catcher’s fingers and toward the pitcher’s body. The advent of the pitch clock has deprived pitchers of the extra time needed to steady themselves during moments of heightened stress.

“In the heat of the battle,” Padres pitching coach Ruben Niebla said, “sometimes that’s the last thing they might be thinking about.”

The proliferation of multi-camera systems has effectively created a surveillance state in which even the most minute movement can be recorded and analyzed. “They’re not just finding it in the game,” Seattle Mariners pitcher Logan Gilbert said. “They’re finding it before you even go on the mound.”

“It’s usually never something that big, honestly,” added Toronto Blue Jays starter Kevin Gausman. “It’s usually something you’re like, ‘How could they even see that?’ A lot of times it’s at an angle where you’re like, ‘Well, they’re not ever going to see that angle.’ But someone might.”

Unlike the sign-stealing scandals that engulfed the sport in the late 2010s, it is legal to use technology to decode a pitcher’s tells, so long as technology is not used to transmit the information in real time. Which leads to moments like the night in August at Petco Park, when the Padres telecast captured a Boston Red Sox coach gazing at an iPad featuring the differing pre-pitch setups of Padres closer Robert Suarez. It also leads to dugouts chirping at opposing coaches at first and third base for venturing outside the coaches’ boxes. There’s a clear purpose for this, said Detroit Tigers pitcher Casey Mize: “so they can get better vantage points of our gloves or our arms to try to relay that.”

When asked which teams excel at this art form, players pointed to the clubs with both the deepest pockets and the keenest eyes: The Boston Red Sox, Los Angeles Dodgers, New York Yankees and Philadelphia Phillies were all mentioned, as were the Cleveland Guardians, Houston Astros and Milwaukee Brewers. To be successful at scoring runs in this era requires the ability to pick up tips.

Even pitchers on elite teams are not immune. Phillies starter Jesús Luzardo altered his delivery earlier this year to avoid tipping. Red Sox starter Lucas Giolito noticed the whiff rate on his changeup decrease because “they know it’s coming,” he said. As Dodgers closer Tanner Scott combusted in September, he cast about for an explanation. “Maybe I’m tipping,” he said. “I have no friggin’ clue right now.”

Even if a pitcher isn’t betraying his next move, hitters routinely attempt to cause unease. That might entail a batter crossing home plate and whispering in the ear of his teammate in the on-deck circle. Or it might involve demonstrative movements on the basepaths. In late April, Padres starter Nick Pivetta grew agitated when San Francisco Giants catcher Patrick Bailey appeared to be relaying signs from second base. Months later, Bailey acknowledged he had been bluffing that night. “You’re just trying to create paranoia,” Bailey said. “I think any chance to get the attention of a guy making pitches, it’s definitely an advantage.”

More often, perhaps, the paranoia is justified. Several hitters suggested that in a given series there is usually one pitcher on the opposing team performing with an obvious tell. “I don’t give too much away, but, I mean, at least one,” Dodgers first-base coach Chris Woodward said. “There’s no question.”

As pitchers rise through the amateur ranks and the minor leagues, they learn the importance of shielding prying onlookers from seeing their pitch grips. In the majors, though, the vigilance extends beyond the basics of glove placement and finger movement. For some pitchers, consulting with video coordinators and working to limit tipping has become a key part of the between-starts routine, and rookies are cautioned about the perils of inattention.

“It can make or break your career,” Dodgers pitcher Emmett Sheehan said. “You can go from being a great pitcher to being a terrible pitcher.”

Padres reliever Jason Adam opted for a larger glove to better disguise his hand. Many pitchers who throw splitters, such as Mize, Gausman and Mariners starter George Kirby, wear long sleeves beneath their jerseys, because finding the grip causes a small ripple in the forearm. “It would just flex, and people would see it,” Kirby said.

A few seasons ago, Dodgers officials met with reliever Alex Vesia and pulled up side-by-side video of his fastball and his slider.

“And they were like, ‘Hey, do you notice anything different in these two videos?’” Vesia said. “I was like, ‘No, I’m coming set the exact same way.’ And they were like, ‘Look at your mouth.’”

Before he threw sliders, he chomped a wad of gum. On fastballs, his jaw stayed still.

He stopped chewing gum.

Alex Vesia was surprised to learn the source of his pitch tipping. (Luke Hales / Getty Images)

“It can be anything,” Cease said. “Where your glove’s positioned. What your head’s doing. What your breathing is. I mean, it can be literally anything. We’ve got to be robots out there, borderline, you know?”

Teams decipher the tips through camera systems like KinaTrax, which offers motion-capture footage of both hitters and pitchers. Analysts study the footage and condense it into reports for the coaching staff. “We have people whose job it is to figure out tips on other pitchers and present that to players who want to be presented with that,” Mize said. And then the coaches present the hints to the players in pregame meetings, which can be reinforced by the in-game usage of iPads that include uploaded footage of at-bats soon after completion. “Hitters always used to do it in the dugout, and they could pick up something,” Padres bullpen coach Ben Fritz said. “But now it’s given to them ahead of time.”

How much value do hitters derive from these tips? It depends on who you ask.

Some hitters love it, especially when facing relievers who tend to throw fewer pitches. The ability to know if the pitch will be a fastball or a breaking ball can be vital. “It’s like having the answers to the test,” Bailey said.

Some find the extra information distracts them from the already arduous task of trying to hit. “I hate the obvious ones,” Yankees outfielder Cody Bellinger said. “Because it’s like, I have to see it and I don’t want to see it. I’m like, ‘F—. Now I can’t un-see it.’”

Some won’t discuss the subject at all. “There’s no way,” said the usually affable Yankees first baseman Paul Goldschmidt, “I’m going to answer any questions about pitch tipping.”

Despite Bellinger’s ambivalence on the subject, he played his part in September when the Yankees demonstrated their skill at uncovering a pitcher’s intentions. The team had picked up something on Blue Jays starter Max Scherzer’s changeup. After Bellinger hit a single, he flapped his arms toward teammate Aaron Judge at second base. Judge made a similar motion whenever Scherzer threw a changeup to Ben Rice, who eventually homered.

The sequence irked Toronto, but most pitchers tend to blame themselves for giving something away with a runner at second base. There is often more irritation when the signaling involves the coaches at first and third base. There were several instances this season of clubs jawing about coaches exiting the designated box to aid hitters.

“I don’t think you should be able to get way down and see something that you shouldn’t be able to technically see in the box,” Tigers ace Tarik Skubal said. “Otherwise, what’s the point of the box?”

According to an MLB official, the Commissioner’s office has instructed umpires to emphasize during their pregame managers’ meeting that coaches should stay within the box. Once the game begins, though, the umpires tend to track the location of the baseball and the actions of the players. The umpires could focus on the coaches at the request of the opposing manager — but since that manager’s club may be engaged in the same activity, there is a lack of incentive to call out the transgression.

To counter the 360-degree spying, the visual aids in the dugouts and the coaches roaming down the baselines, some pitchers have resorted to subterfuge in the form of faking tips. On occasion, when dealing with a pesky runner at second base, Gilbert will open his glove as if searching for his curveball grip only to switch back to a fastball. Gausman likes messing with hitters’ heads.

“Maybe I’ll do the same thing on three pitches in a row,” Gausman said. “And on the fourth one, it’ll be the same pitch, but I’ll do something different. You’ll be amazed, you do one extra flick of the glove, and they’ll be like, ‘Well, he’s thrown three fastballs. He didn’t do that the first three.’ So automatically, they’re like, ‘Oh, he’s throwing an off-speed pitch.’”

For most pitchers, though, the prospect of pretending to tip adds another layer of thought to an already complicated endeavor. The clock also reduces the time for tomfoolery. So the best bet, several pitchers said, was not to worry too deeply about the other team’s intel. Hitting is still quite difficult: the league-wide batting average in 2025 was .245, nine points lower than it was in 2015.

“I always tell guys, too: the 2017 Astros still got out,” Strahm said before the postseason began. “Just make your pitch.”

Facing Hernández at Citizens Bank Park on Saturday, Strahm might have tipped his pitch. Pages might have given Hernández a clue on the setup of catcher J.T. Realmuto. Or it could simply be this: Hernández, a three-time Silver Slugger, teed off on a belt-high 91 mph fastball.

For Weaver, who was once considered one of Yankees manager Aaron Boone’s most trustworthy late-inning relievers, there may not be any more opportunities to overcome the tipping. He acknowledged the challenge of maintaining his composure while splitting his focus between the opposing hitters and his own body.

“I’ve just got to be tidy, clean, and go out there and give myself the best chance,” Weaver said. “But ultimately, too, you’ve got to keep your brain clean and clear. The moment’s already big. You don’t need more things stacking up on your plate.

With reports from The Athletic’s Brendan Kuty

(Illustration: Will Tullos / The Athletic; Photo: Luke Hales/Getty Images)