Melanie Sepulveda, a Staten Island teacher, had her doubts about the new “bell-to-bell” cellphone ban in New York schools.

In the past, she watched students drift through the hallways at I.S. 27 Anning S. Prall, looking at their phones and feet. Some pre-teens, entrusted with bathroom passes, filmed TikTok videos outside her English classroom where a quiet corridor, save for a few offices, gave cover to their scheme.

This school year is different. When students arrive in the morning, I.S. 27 collects the phones for the full school day, even during lunch and free periods. Kids adjusted quickly. One of Sepulveda’s students, with no phone for distraction, brought a SpongeBob LEGO Set to use during recess. The activity got the girl and her classmates talking, so much so that they ran out of time to build it that first day.

“I don’t even have the words to explain the trepidation I had going in about how the kids were going to be like, jonesing and freaking out,” said Sepulveda, who teaches seventh graders, “compared to the impression I have of how well it’s going.”

A month into the school year, a clearer picture of how New York City public schools have implemented Gov. Hochul’s phone ban is coming into focus — with students, parents and teachers reporting fewer distractions in the classroom and a smoother transition than some had feared.

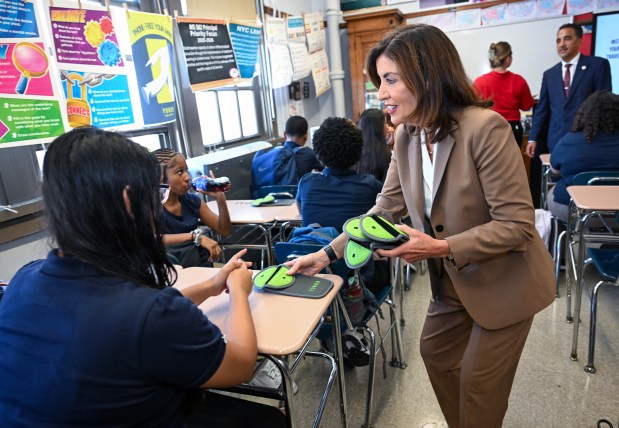

Gov. Kathy Hochul highlights distraction-free schooling by showing students new Yondr cell phone pouches at M.S. 582, The Magnet School for Multimedia Technology and Urban Planning, on Thursday, Sept. 4, 2025. (Susan Watts / Office of Governor Kathy Hochul)

Gov. Kathy Hochul highlights distraction-free schooling by showing students new Yondr cell phone pouches at M.S. 582, The Magnet School for Multimedia Technology and Urban Planning, on Thursday, Sept. 4, 2025. (Susan Watts / Office of Governor Kathy Hochul)

The law, which went into effect this fall for all school districts and charter schools across the state, responds to a growing recognition that phones can be detrimental to children’s mental health, academic progress, and social skills.

Some teens have approved exemptions, and others just try to circumvent the new rules. But on the whole, families and school staff described a cultural reset where the phones and social media no longer dominate the hallways and cafeterias.

The city’s schools chancellor, Melissa Aviles-Ramos, reflected in an email that students are not only learning with fewer distractions, but also truly connecting with their classmates through “lunchtime dance parties, hallway chatter, and in-classroom discussions.”

“We are excited to see the continued impact of this policy,” the chancellor said.

Cell phone pouches are pictured on the first day of school at HBCU Early College Prep High School in Queens, New York, on Thursday, Sept. 4, 2025. (Michael Appleton / Mayoral Photography Office)

Cell phone pouches are pictured on the first day of school at HBCU Early College Prep High School in Queens, New York, on Thursday, Sept. 4, 2025. (Michael Appleton / Mayoral Photography Office)

Christian, a seventh grader at P.S./I.S. 78 in Queens, said his school already restricted phones, but this year started requiring velcro pouches for the devices. It hasn’t been too hard of a transition: The main difference is he has to wait until he’s put his pouch in a bin and exited the school building to use his device.

Christain said it feels different to talk to his friends on the phone, compared to in person. “Online, like messaging, you can’t really see their expression or just actually talk more, instead, just like, a few minutes or so, then they have to go.”

Christian’s mom, Whitney Toussaint, is just glad he’s paying attention.

“I couldn’t imagine being a teacher and having to compete with the smartphone,” Toussaint said. “The kids are there to learn and pay attention in class, and not text each other during class or play games during class.”

At Edward R. Murrow High School in Brooklyn, one of the city’s largest schools with about 3,500 students, administrators opted for “PhonX3” pouches from the vendor Faraday, which block cell signal and open with velcro. They’re also rolling out translation devices for English learners who used their phones for that purpose.

But the biggest deterrent has been the existence of a law, more authoritative than a school policy could ever be.

“They did not think it was just coming from us inside the school. We were not being quote-unquote ‘haters,’” said Terrain Reeves, an English and media communications teacher. “We were actually enforcing not just a policy, but a law that’s written on the books.”

During the first month of school, Reeves caught a student with a phone, who protested that he had an online business to run. He did not face disciplinary action for the infraction, which as required by law must be frequent or otherwise egregious to result in any real consequences.

“You can just look at them if you see them with the phones, and they know to put it away,” Reeves said. “It doesn’t mean they won’t test us — and that’s being teenagers.”

“The students, they’re expecting because you’re teachers, you’re also blind and can’t see them with their phone!” she joked.

Maria Hantzopoulos, a mom of two students at western Queens high schools, said she’s been “pleasantly surprised” by how much she likes the new policies.

“If you had asked me a month ago, I would’ve said it would be a power struggle with kids. It’s going to be hard to enforce, are they going to have the staff to do it?” said Hantzopoulos, who was also a former teacher in the city’s public schools before the rise of smartphones.

But after the COVID-19 pandemic, when her kids were in third and sixth grade, and all instruction delivered through a computer, she appreciated “a detox from that, many years later.” A co-president of her daughter’s PTA, she brought in UNO for students to play at lunch. Her son, a freshman, came home from his new school one day with the phone numbers of 10 recent friends written on his arm, because he couldn’t immediately add them to his phone’s contact list.

“I don’t even hear complaints from my kids at this point. They were complaining at the beginning,” Hantzopoulos said. “It’s just like they accepted it. It’s a nonissue at this point.”

Manhattan’s School of the Future phased in its phone restrictions over multiple school years, starting with sixth graders. By the time the state’s ban was in place, the vast majority of students already knew the drill: Put your phone in a Yondr pouch, where it will stay locked until the end of the school day.

“I feel like I can actually do real teaching again, because I’m not competing with this device for a kid’s attention,” said Jeremy Copeland, a 12th grade history teacher. “The teacher’s there to teach, and not be the phone warden.”

In the absence of phones, students have found other ways to pass their free time. There’s been a “slight resurgence” of digital cameras, as teens get creative to document their high school years, Copeland said. The teacher also reported an uptick in the number of student groups, including a new spelling bee club.

“Kids know that during lunch or during a free period, they’re not going to have that digital security blanket to hold on to, and they have to interact with their peers. So why not do it in a setting where they get to talk with people who have common interests and enjoy similar activities?” Copeland said.

“As sometimes overstimulating as the murmur of dozens of voices conversing at the same time can be, it’s a pleasure to hear,” he added. “I’ll take that any day over watching 15 people stare at their phones in silence in the same room.”