A tall, barrel-chested redhead sold cars with an eye on the future. He was bold and loud and rich and saw what no one else could see: a professional sports franchise transforming an old town into a modern metropolis.

Like a biblical prophet, the car dealer was a visionary, a voice in a wilderness of unbelief. When civic leaders planned HemisFair ’68 to modernize San Antonio, B.J. “Red” McCombs recognized one of its buildings as a catalyst for the city’s future.

A businessman from the West Texas burg of Spur (pop. 863), McCombs imagined HemisFair Arena as the home for a pro sports team, a venue that would draw thousands of fans and attract national media.

Opportunity beckoned in 1973. The Dallas Chaparrals of the American Basketball Association went on the market. Angelo Drossos, a local stockbroker, wanted a group of local businessmen to buy the team and asked McCombs to be the lead investor.

“San Antonio didn’t have a bad image; it had no image,” McCombs wrote in his 2010 memoir “Big Red.” “We needed a major professional sports team to get on the radar.”

According to “Big Red,” McCombs and his group leased the team for $200,000 with an option to buy after one year. One investor told McCombs, “You can count me in. But as far as pro basketball goes, I’d rather watch water drip from a faucet.”

Red McCombs with the Spurs Coyote in 1973. Credit: Courtesy / McCombs Family

Red McCombs with the Spurs Coyote in 1973. Credit: Courtesy / McCombs Family

A team re-named the Spurs played its first game on Oct. 10, 1973 and drew 5,879 people in a venue that held 10,070.

“I remember going to the opening game,” former mayor and former Bexar County Judge Nelson Wolff told the San Antonio Report. “It was so nondescript. I didn’t think it was a big deal.”

At the time, local fans showed equal or more enthusiasm for pro wrestling at Municipal Auditorium north of downtown, which held 6,000.

“It was not uncommon for a big wrestling match to draw 2,000 and 3,000 and maybe even a sellout,” said former Express-News sports editor Barry Robinson. “I’m sure some wrestling matches drew more (fans) than some Spurs games.”

Only 1,799 people came to watch the Spurs win their first game on Oct. 16. In that contest, a slender Virginia Squires forward impressed with silky moves and finger rolls. McCombs told Drossos, “We ought to see if we can get this kid on our team.” Within months, McCombs had signed the Spurs’ first box office draw, George Gervin, a future Hall of Famer.

McCombs’ vision expanded incrementally from star to star and era to era, from Gervin to David Robinson to Tim Duncan to Victor Wembanyama. The Spurs grew with San Antonio and San Antonio grew with the Spurs, city and team intertwining until the two became recognized as one outside the U.S.

Mention San Antonio to people in Argentina, Italy and France, and one word rolls off the tongue: Spurs. Locals who travel aboard have stories. Here’s one: In May 2021, a journalist and his wife took a river cruise on the Danube in Europe.

“Our lunch server knew a lot about the Spurs and recited four or five names of players — Tony [Parker], Tim, Manu [Ginobili], David Robinson,” said former Express-News reporter David Hendricks. “It was all he knew about San Antonio.”

Pre-HemisFair ’68 San Antonio was known for the Alamo. Now it is arguably best known for a basketball team. The evolution from American outpost to global destination is a unique story. To paraphrase former Mayor Henry Cisneros: No other professional sports franchise in the U.S. has transformed a city’s identity the way the Spurs have transformed San Antonio’s.

Fifty-two years later, McCombs’ vision continues to grow. Plans for an estimated $3 billion to $4 billion sports and entertainment district have emerged from the very ground that gave birth to his vision: Hemisfair. McCombs did not live to see the proposed downtown Spurs arena and surrounding development known as Project Marvel.

In one of their only chances to weigh in on the larger vision, voters will decide on Bexar County’s portion of a complicated funding structure for the arena in a venue tax election Nov. 4.

Marsha Shields, McCombs’ daughter, says she knows how her father would feel.

“I am confident that if he were here, Red McCombs would be doing everything he could to support the new arena, the entertainment district and the convention center expansion,” Shields said. “Our downtown is ripe for revitalization and having the Spurs as the anchor tenant back at Hemisfair is a full-circle opportunity.”

The hope of HemisFair and ‘Ice’

Civic leaders in the early 1960s wanted to bring a world’s fair to San Antonio (pop. 587,718 at the time). As the nation’s 17th largest city, San Antonio lacked capital, clout and an international profile. It also faced a nearly impossible requirement: persuading at least 20 major companies to present industrial pavilions at the fair.

Banker Tom C. Frost IV raised capital. McCombs pursued Fortune 500 companies. Using a powerful network of connections, he secured Humble Oil, Southwestern Bell and other Texas corporations. Wanting a national corporation, he called Lee Iacocca, a Ford Motor Company vice president. A heated conversation ensued.

Iacocca declined McCombs’ request, calling San Antonio “that dusty little town of yours,” which prompted an exchange of profanities, according to “Big Red.” McCombs hung up and played a hidden advantage.

He complained to good friend, Texas Gov. John Connolly, a close ally of President Lyndon B. Johnson, also a Texan. Connolly told McCombs to call Iacocca back with a warning: The President would be calling him soon. When HemisFair opened on April 6, 1968, Connolly and Henry Ford II posed for a photo in front of the “Wide World of Ford” exhibit.

The world’s fair attracted six million visitors, launched the city’s modern tourism industry and created landmark structures, such as the Tower of the Americas, the Henry B. González Convention Center and the Hilton Palacio del Rio. Once the six-month fair ended, the shine on the city vanished. By 1973, San Antonio was once again known for a historic battle in 1836 — plus 92 acres of dormant downtown land.

Images of the monorail at HemisFair ’68 are displayed at the Institute of Texan Cultures in 2018. Credit: Courtesy / UTSA Special Collections at ITC

Images of the monorail at HemisFair ’68 are displayed at the Institute of Texan Cultures in 2018. Credit: Courtesy / UTSA Special Collections at ITC

One remnant of the property, HemisFair Arena, offered a glimmer of hope. It became a popular concert venue — Elvis Presley, Johnny Cash and Led Zeppelin performed there in the early days — and a not-so-popular home for the Spurs.

At the time, the ABA was trying to sell Gervin’s team, the Virginia Squires. To prevent the depletion of the team’s roster, ABA commissioner Mike Storen announced there would be no more trades or cash deals with the Squires. In “Big Red,” McCombs wrote that he ignored the directive and had Frost Bank wire $300,000 to Squires owner Earl Foreman. The transaction was sent to the league for approval.

Storen denied the deal and warned: If you play Gervin, the Spurs will forfeit every game. To counter that move, Drossos hid Gervin in a local motel and McCombs sought a federal injunction to restrain the league from enforcing the rule. The Spurs prevailed in court.

On Feb. 7, 1974, a 6-foot-7-inch forward took the floor with a nickname acquired in Virginia: Iceman. Gervin became an instant fan favorite, gliding to the basket, scoring in bunches, leading the team to a 45-39 record. “Ice’s” arrival sparked a 40% increase in attendance, from 5,554 through the first 30 home games without him to 7,796 over the final 12 games of the season.

Wanting to fill the arena in the Gervin era, McCombs gave tickets away. “He recruited people to the games,” said Shields, CEO & Managing Partner of McCombs Enterprises. “He got basic trainees from Lackland to bring people. He got United Way to bring people. He did whatever he could to get people in seats. And it worked: After a few years, the arena became too small.”

The team captured the city’s heart. Under new coach Doug Moe, the Spurs joined the NBA in 1976 and led the league in scoring, averaging 115 points per game, and won their first division title. To accommodate a fan base gone berserk, the City Council in 1977 approved $4 million to raise the arena roof by 33 feet and add 6,000 seats. As 38 hydraulic jacks lifted the 2,260-ton roof inch by inch, San Antonio’s profile rose with it.

The original JumboTron at the HemisFair Arena. Credit: Courtesy / Spurs Sports and Entertainment

The original JumboTron at the HemisFair Arena. Credit: Courtesy / Spurs Sports and Entertainment

Locals once indifferent to pro basketball became the loudest and rowdiest fans in the NBA. A contingent of enthusiasts known as the Baseline Bums drew national attention, taunting opposing players and dousing some with beer. During one 10-cent beer night, they exacted revenge on a visiting coach. After the Bums read an insult from Denver Nuggets coach Larry Brown (“The only thing I like about San Antonio is their guacamole salad”), they waited for him to emerge from the arena tunnel and pelted him with avocados.

“Ice” reveled in the atmosphere. “People were scared to come in here and play us,” Gervin told Texas Monthly in 2023. “If Big George (Valle) and the Baseline Bums didn’t get ’em, we’d run ’em to death on the floor. I’ve never seen anything like it.”

The Spurs became a top league draw, averaging 11,932 fans in 1978-79, more than the Los Angeles Lakers (11,771) and Boston Celtics (10,193), and their venue developed a reputation as the noisiest in the NBA.

Sports Illustrated took notice. In a 1982 piece headlined, “Best Team You’ve Never Seen,” the magazine lavished praise on Gervin, who was headed for a fourth NBA scoring title, and gushed over the Spurs for winning three division titles with one of the league’s lowest payrolls.

“Despite those accomplishments,” SI’s Bruce Newman wrote, “they have been on national television only twice in three seasons, most recently almost two years ago. Unless it had been in Boston or Los Angeles, the Alamo wouldn’t have been covered by CBS, either.”

Big business and the White House

The “dusty little town” described by Iacocca grew into a metropolis. In 1994, 26 years after the Spurs arrived, San Antonio boasted three Fortune 500 companies — AT&T, Valero Energy Corporation and Tesoro Corporation — and a population of 1 million, which, at the time, ranked ninth in the U.S.

During this period, McCombs sold his stake in the Spurs (1982), repurchased his interest in the franchise (1986), then sold it again (1993). As the team elevated the city’s profile, a young political leader emerged from San Antonio’s West Side. Henry Cisneros won election to City Council in 1975, became mayor in 1981 and was named U.S. Secretary of Housing and Urban Development in 1993.

As mayor, Cisneros envisioned San Antonio as a sports destination. He wanted to build a facility that could attract an NFL team and host major events, such an NBA All-Star Game, NCAA regional tournament basketball games and a U.S. Olympic Festival, the nation’s largest junior sporting event. In 1987, he and an aide, Robert Marbut Jr. marshaled a proposal through the Texas Legislature to build a domed stadium with a half-cent sales tax, pending voter approval.

Cisneros also brought economic investments to San Antonio, using the Spurs as part of his pitch. One of his most important yet little-recognized accomplishments was recruiting a 7-foot-1-inch Navy ensign to the city.

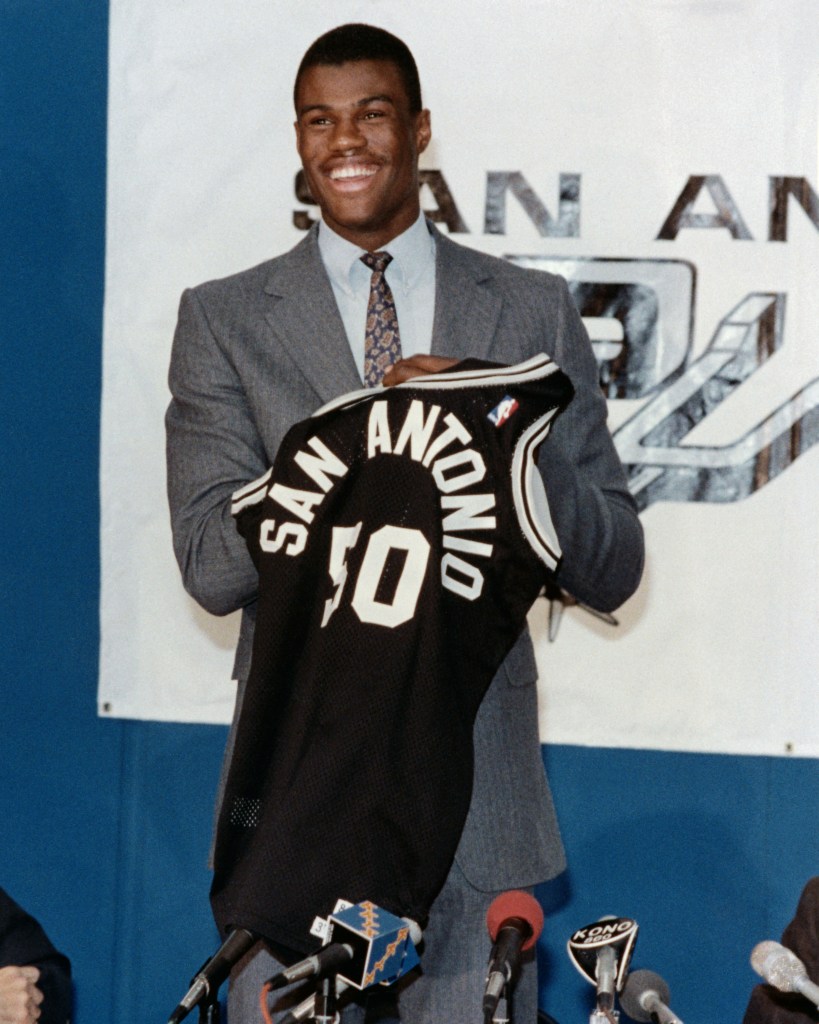

David Robinson #50 of the San Antonio Spurs speaks with media following the 1987 NBA Draft in San Antonio, Texas. Credit: NBA Photos via Getty Images

David Robinson #50 of the San Antonio Spurs speaks with media following the 1987 NBA Draft in San Antonio, Texas. Credit: NBA Photos via Getty Images

In 1987, the team won the NBA Draft Lottery and selected David Robinson, known as The Admiral. Winning the lottery both elated and worried the fan base. While Robinson was a generational talent, a military obligation clouded his future. He could serve his country, re-enter the draft and sign with the Lakers or another team.

Envisioning Robinson as a city pillar, Cisneros pursued him as if he were a Fortune 500 CEO. The mayor appealed to his character, telling Robinson the city wanted him as a community leader. Cisneros gave him a helicopter tour of San Antonio, pointing below to landmarks, neighborhoods and schools.

Though the team had been mired in a slump, winning only 28 games in 1986-87, Robinson signed. The Los Angeles Times lamented his decision: “Spurs, by winning, wooing Robinson, broke Laker hearts.”

Robinson’s play illuminated the city’s profile. As a rookie in 1989-90, he led the Spurs to the Midwest Division title and a 56-26 record, a 35-game improvement that marked the greatest turnaround in NBA history. He ran like a guard, jumped like an Olympian and posted dazzling numbers, averaging 24.3 points, 12 rebounds and 3.9 blocks per game.

President Clinton and Henry Cisneros walk together circa 1995. Credit: Photo of a projected image presented during a banquet in honor of Henry Cisneros

President Clinton and Henry Cisneros walk together circa 1995. Credit: Photo of a projected image presented during a banquet in honor of Henry Cisneros

Cisneros followed the Admiral closely after leaving the mayor’s office. As Housing Secretary in the early 1990s, he attended a memorable Cabinet meeting at the White House. President Bill Clinton asked if Cisneros had watched the Arkansas Razorbacks, Clinton’s favorite football team.

“No,” Cisneros said. “I was watching the Spurs.”

The President’s eyes lit up. “He went off talking about how much he loved the Spurs and the player he thought so highly of was David Robinson,” Cisneros recalled. “The President said, ‘He’s got a good shot for a big man. He can dunk from inside or shoot from the outside.’ He has his mind on things like nuclear proliferation and the trade deficit with Japan. And he’s more interested in talking about the Spurs.

“What was impressive was how many others in the Cabinet meeting knew about David and the Spurs. That was the first time I figured out that the Spurs had become a household name.”

Near-disaster and breakthrough

The Alamodome opened in 1993. Designed for an NFL team, the $186 million, 64,000- seat facility served the Spurs instead. It was funded by a narrowly approved sales tax increase.

Replacing HemisFair Arena, outdated and razed in 1995, the dome was mocked for its design. Critics griped that it looked an upside-down armadillo. Worse, the facility was cavernous and players complained that it was drafty, while fans contended with poor sight lines.

For all its flaws, the dome was good to the Spurs. They won two division titles and advanced to the playoffs five times in their first six seasons there. Injuries to Robinson led to 62 losses in 1996-97 and a second NBA Draft Lottery jackpot. The Spurs drafted Tim Duncan, who would become the greatest power forward in league history.

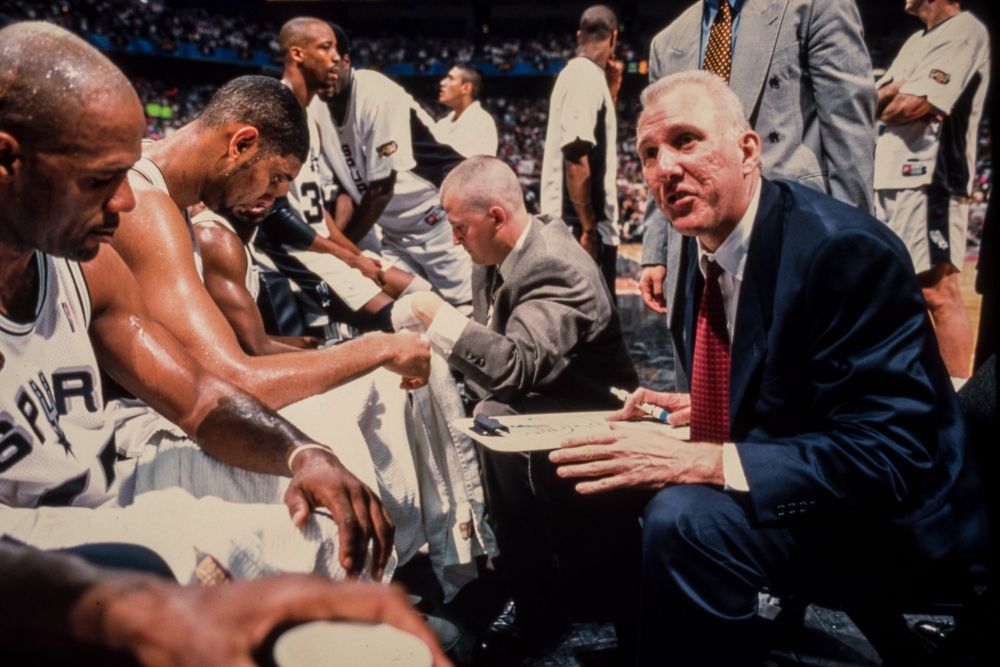

Under second-year coach Gregg Popovich, the Spurs emerged as a serious title contender, drawing crowds of more than 30,000. Economic challenges, however, threatened the franchise’s future.

Spurs Coach Gregg Popovich huddles with players in a timeout during the NBA Finals in 1999. Courtesy / San Antonio Spurs Credit: Courtesy / San Antonio Spurs

Spurs Coach Gregg Popovich huddles with players in a timeout during the NBA Finals in 1999. Courtesy / San Antonio Spurs Credit: Courtesy / San Antonio Spurs

With NBA arenas trending toward luxury boxes, club seats and naming-rights deals, the Alamodome looked like a dinosaur. United Airlines paid $1.8 million annually for naming rights to the Chicago Bulls’ arena, which held 160 luxury suites. Fleet Bank paid $30 million for 15-year naming rights to the Boston Celtics’ arena, which featured 104 luxury suites. The Alamodome had 34 suites and no named sponsor.

Spurs ownership, led by chairman Peter Holt, wanted a new, sponsored facility to compete. Building one would require a tax increase, officials at the time decided. Polling showed voters would reject a sales tax increase, so a tourist tax was placed on the ballot instead.

Given the bitter and bruising sales tax battle to fund the dome in 1989, players and fans grew nervous. Meanwhile, New Orleans mayor Marc Morial called for an effort to bring the Spurs to Louisiana if voters rejected the tax increase. Other cities also expressed interest. The pressure to relocate grew.

To keep the franchise in San Antonio, the Spurs needed to mount a campaign for the ages, one that started on the court. Fueled by a shot known as the Memorial Day Miracle, they delivered, winning their first NBA championship on June 25, 1999, in Madison Square Garden. From San Antonio, McCombs called Holt and Popovich to congratulate them and reveled in headlines like this from The New York Times: “Spurs win title as Knicks dream ends.”

Drone image of the Alamodome in downtown San Antonio taken in August 2025, facing toward the northeast. Credit: Cooper Mock for the San Antonio Report

Drone image of the Alamodome in downtown San Antonio taken in August 2025, facing toward the northeast. Credit: Cooper Mock for the San Antonio Report

Five months later, voters approved a hotel occupancy and car rental tax increase for a new Spurs arena. In 2002, the team moved into the SBC Center, owned by Bexar County on the East Side, an 18,500-seat facility with 50 luxury suites and excellent sight lines.

The Alamodome remains operational. More than three decades after opening, the Spurs’ second home has drawn more than 30 million visitors to concerts, high school and college football games, NCAA Final Four men’s and women’s tournaments and other events.

Going global

Before the fall of the Berlin Wall and the collapse of the Soviet Union, an assistant Spurs coach made a discovery that would change San Antonio and revolutionize the NBA. In June 1989, Popovich attended the European championships and noticed rosters littered with future NBA talent.

Arvydas Sabonis of the former Soviet Union, for example, would star in Portland and Toni Kukoč of the former Yugoslavia would excel in Chicago. One month later, the Spurs signed their first international player, Zarko Paspalj from Serbia.

As Popovich continued to scout overseas, he recognized that foreign players were more fundamentally sound than Americans. Another assistant coach, R.C. Buford, also developed an appreciation for international talent and later became director of scouting.

In the summer of 1997, Buford flew to Melbourne, Australia for the FIBA 22-and-Under World Championships. His soon-to-be legendary eye for talent locked in on a raw but gifted kid from Argentina, Manu Ginobili.

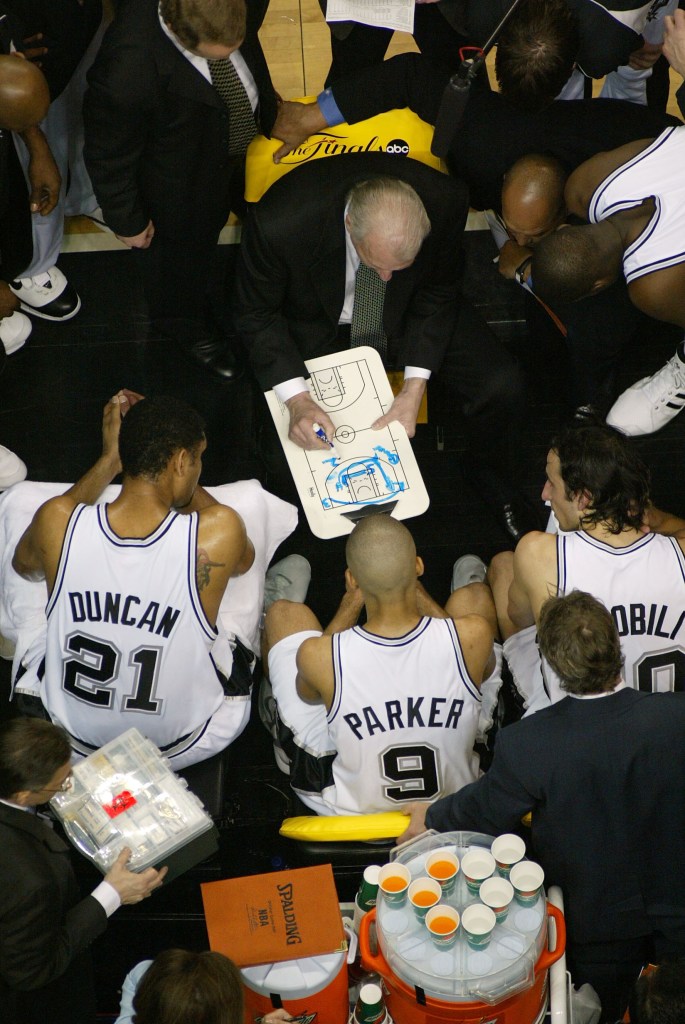

The San Antonio Spurs play against the Detroit Pistons in Game Six of the 2005 NBA Finals on June 21, 2005 at SBC Center in San Antonio. Credit: Photo by Chris Birck/NBAE via Getty Images

The San Antonio Spurs play against the Detroit Pistons in Game Six of the 2005 NBA Finals on June 21, 2005 at SBC Center in San Antonio. Credit: Photo by Chris Birck/NBAE via Getty Images

“He was just a crazy wild horse,” recalled Buford, now CEO of Spurs Sports & Entertainment.

Buford noticed something else. Only seven NBA teams had scouts at the world championships.

Not one of them recognized the Argentine’s potential. Two years later, the Spurs selected Ginobili with the 57th pick in the NBA Draft and allowed him to develop in Europe.

Around the same time, Buford discovered a super quick, teenage point guard in France. With the 28th pick of the 2001 draft, the Spurs selected Tony Parker from a club in Paris. Two years later, Ginobili joined the Spurs.

Parker, Ginobili and Duncan, a Virgin Islander, propelled the Spurs and the NBA into a new era. As the Big Three won championships in 2003, 2005, 2007 and 2014, the league exploded with international talent and attracted a global television audience.

Spurs-crazed fans emerged from all over the world:

In 2003, Jurgen Aspers left a bank job in Weert, Holland, and flew to San Antonio to follow the Admiral’s final playoff run. “Only one month of vacation was allowed,” Aspers said. “I needed two to witness the glorious last ride of David Robinson into the sunset. So I followed my feeling and quit my job.”

Perla Manapol followed the Spurs from remote villages in the Philippines. Wanting to catch the score of a playoff game in the Big Three era, she paid a farmer in a Palawan jungle to climb a coconut tree with her cell phone and look for a signal. The farmer called down scores for more than an hour before telling her the Spurs had won. “You can imagine the yelps and yahoos that reverberated throughout the jungle on that day,” Manapol wrote in an email to this reporter in 2007, “most possibly contributing to ecological disturbance.”

Dong Wang, a sports anchor from Best TV in Shanghai, stood on the floor of the Frost Bank Center in June 2013, one of 350 media members from 34 countries covering the NBA Finals.

Samuel Dalembert of the Philadelphia 76ers and Tony Parker of the San Antonio Spurs read to children after a dedication ceremony at the Hui Lei school, north of Beijing on Saturday, July 16, 2005, as part of Basketball Without Borders. Credit: AP Photo / Greg Baker

Samuel Dalembert of the Philadelphia 76ers and Tony Parker of the San Antonio Spurs read to children after a dedication ceremony at the Hui Lei school, north of Beijing on Saturday, July 16, 2005, as part of Basketball Without Borders. Credit: AP Photo / Greg Baker

He was explaining the popularity of the Big Three in China to a local reporter.

“There are posters of them everywhere,” Dong told Spurs.com. “If you asked Tim Duncan to go to China right now, he could not go to any street because he would be surrounded and mobbed by people who would be asking for autographs.”

On June 15, 2014, Jane Ann Craig aimed her camera at the most internationally packed NBA champions in history: 10 Spurs from seven foreign countries. From her seat in section 101, row 9, she zoomed in on athletes celebrating with flags from Argentina, France, Brazil, Italy, Australia, Canada and New Zealand.

Through her camera lens, Craig captured a rainbow of reds and blues, yellows and greens. A global melting pot. The image blurred as she wept.

“It was emotional to see them standing together on the stage, wrapped in the flags of their countries,” she said. “A band of brothers.”

A season ticket holder since 2008, Craig makes a 150-mile roundtrip journey from her home in Austin to attend home games. She has flown to Memphis, Portland and Miami to watch playoff games. She befriends fans from other countries and once chauffeured a Facebook friend who flew in from China.

Six years after following her Spurs around the country, camera in tow, Craig finally captured a championship: the 2014 title game that was broadcast to 215 countries and territories in 47 languages.

The rise of Victor Wembanyama

Joe Shields rose from his floor seat at Frost Bank Center, eyes wide, mouth agape. A 7-foot-5-inch rookie had sprinted past him like a point guard, knocked down a 3-pointer and blocked a shot, all within 60 seconds of tipoff. The crowd erupted. Shields felt the thunder of a playoff atmosphere. But it was the first home game of the 2023-24 season, and just like that, Victor Wembanyama had expanded McCombs’ vision.

“More eyeballs in France and Europe are on the Spurs,” said Shields, the son of Marsha Shields and grandson of McCombs.

The Spurs have built a model franchise. Hall of Fame coaching, revolutionary scouting, and exceptional drafting and player development are franchise cornerstones. They’ve also hit the NBA draft lottery three times. Their first two No. 1 lottery picks, Robinson and Duncan, became Hall of Fame players. The third, Wembanyama, is a generational talent who broke into the league under Popovich, the NBA’s all-time winningest coach when he retired earlier this year with 1,390 victories.

A fan cheers as rookie Victor Wembanyama, the San Antonio Spurs’ first overall draft selection from France, plays in his first regular season NBA game at the Frost Bank Center in 2023. Credit: Scott Ball / San Antonio Report

A fan cheers as rookie Victor Wembanyama, the San Antonio Spurs’ first overall draft selection from France, plays in his first regular season NBA game at the Frost Bank Center in 2023. Credit: Scott Ball / San Antonio Report

The Spurs issued more than 200 media credentials for Wembanyana’s first home game, more than 20 of them to foreign outlets. One of 53 foreign players to have competed for the Spurs, Wembanyama’s appeal spans the globe.

Although they haven’t won a title in 11 years, the Spurs continue to draw fans and tourists, filling hotels and restaurants. Approximately seven million visitors came to San Antonio when the Spurs arrived in 1973. Fifty years later, the city attracted more than 37 million.

There is no way to measure the team’s precise impact on tourism. But the Spurs report the following: Roughly 25% of season ticket holders and approximately 30% of single-game buyers come from outside Bexar County. Two percent of ticket buyers come from outside the U.S.

How much these visitors contribute to the local economy is the subject of considerable debate. One study by Stone Planning LLC estimated the Spurs’ economic impact at $9.2 billion over the last 20 years. Skeptical about the lofty projections, Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones called for an “independent economic analysis” in August. She argued that the Stone Planning study did little to evaluate the impact of a new arena and leaned heavily on data provided by the Spurs.

Another study by economists John Charles Bradbury and Brad R. Humphreys argued for “the decades-old consensus of very limited economic impacts of professional sports teams and stadiums.”

Whatever the truth, the Spurs believe Project Marvel represents the next evolutionary step for San Antonio. A new $1.3 billion arena will anchor a downtown entertainment district, featuring an expanded Convention Center, upgrades to the Alamodome and a new hotel and performing arts center.

“This is going to be a place that brings people together again, which is what we do best in San Antonio,” Buford said.

A rendering of the San Antonio Sports and Entertainment District. Credit: Courtesy / Populous

A rendering of the San Antonio Sports and Entertainment District. Credit: Courtesy / Populous

Opponents of Project Marvel claim the estimated benefits — $18.7 billion over 30 years, according CSL International — are inflated, while elements unmentioned in the term sheet, like moving a SAWS water plant and purchasing land for the arena, present a low-end estimate of the cost to taxpayers. They also contend that public funding should be spent on community needs like affordable housing, health care and infrastructure, though the complexities of venue and hotel occupancy tax limitations have further muddied the issue.

As the debate continues, the Spurs and the city have agreed to fund most of arena. Bexar County voters will decide on Nov. 4 whether to contribute the remaining $311 million to the project.

Visit San Antonio, the city’s marketing arm, uses the Spurs to enhance the city’s global identity. Visit San Antonio promotes the team to travel resellers who have access to tickets in Mexico. It also contracts with agencies in the United Kingdom, Canada and China.

“The San Antonio Spurs are one of the city’s strongest global ambassadors,” said Mario Bass, Visit SA’s CEO and President. “Their championship culture not only elevates our city’s reputation but also helps attract major sporting events and inspire travel to San Antonio. Every game hosted in the Alamo City and broadcast around the world is an opportunity for our city to shine. Through the Spurs, the world is shown San Antonio’s authentic culture, rich and historic food and fiesta spirit.”

Community spirit cannot be measured. Neither can the ability of one team to energize and unify a city. These are intangibles, many Marvel supporters and skeptics agree, that set San Antonio apart.

“Cities struggle to find things to unify around,” Cisneros said. “And the Spurs are undoubtedly the principal unifier in San Antonio. Just remember those nights when every arterial into downtown was packed with pickups and honking cars and people coming out of hotel balconies and restaurants. I got caught in one of those crowds and it took me a couple of hours to get home. But I wanted to be part of the championship celebration.”

Twenty two years after flying from Holland to San Antonio for the 2003 playoff run, Aspers, 48, remains a huge fan. A photo of him seated on the Spurs home court logo anchors his Facebook page.

“Forty wins this season and we make it to play-ins,” Aspers predicted in Facebook Messenger to the San Antonio Report. “Write that down. Season after that, a new dynasty will be upon us. GO WEMBY GO!”

Fans around the world share his passion. More than 70% of the team’s 6.7 million Facebook followers and more than 72% of its 5.3 million Instagram followers are international. The team has invested in an Instagram channel in France, LesSpurs, and boasts more than six million followers on a microblogging platform in China called Weibo.

The Spurs’ global identity expanded in January with two games in Paris against the Indiana Pacers. In the first, Wembanyama brought down the house. He scored 30 points, grabbed 11 rebounds, dealt six assists and blocked five shots, leading the Spurs to a 140-110 victory. In the second, Wembanyama dropped 20 points and grabbed 12 rebounds in a 136-98 loss.

Another set of numbers stunned: The NBA Paris Games, as they were called, generated more than 718 million views on social media, a record. Fans from 53 countries and territories bought tickets to the games, which sold out within 24 hours. Content featuring Wembanyama in Paris turned him into the second most-viewed NBA player across NBA social media accounts with more than 836 million views.

After McCombs passed away in 2023, Shields and the McCombs family rejoined the franchise’s ownership group, completing a circle-of-life journey. At the end of that first season in 1974, McCombs and his investors exercised their option to buy. The final purchase price was $800,000. Today, Forbes estimates the Spurs’ worth at $3.85 billion.

The original investors did not expect to make money, according to “Big Red.” They simply hoped to bring national attention to San Antonio.

Now they have the eyes of the world.