By the time Vincent DeLuca met Rafael Larraenza, they had already connected, in a way, many years before.

DeLuca grew up in Oceanside and Vista, in a community where a lot of his friends were the children of immigrants. The father of one of his best friends was from Mexico City and had been picked up by U.S. Border Patrol agents and sent back across the border. When his dad tried to come back, he had gone missing in the mountains and later died. DeLuca was around 18 at the time, and it was a traumatic experience for the family and their community.

“I was very close with his son; he’s one of my best friends and I knew him really well, I knew his father really well. So, all of these years later, when I found out about Rafael and we started to work on the film, I actually went back to my friend. I asked him if, when his dad went missing, did he reach out to anyone for help.” DeLuca said. “He said, ‘I contacted this man named Rafael.’ It was just sort of weird that there were these touch points where my own experience was intersecting with Rafael’s all these years later.”

Larraenza has spent the past 25 years searching the U.S.-Mexico border region for people who are lost or missing during their migration, through his organization Angeles del Desierto (Desert Angels), which he runs with his wife, Monica. DeLuca, who had studied law and Latin American politics, and worked migrant farm workers and as a lawyer at the Legal Aid Society of San Diego, was working on a screenplay centered on the border when his wife suggested going a bit further in his research. He came across a news story about Larraenza and was inspired.

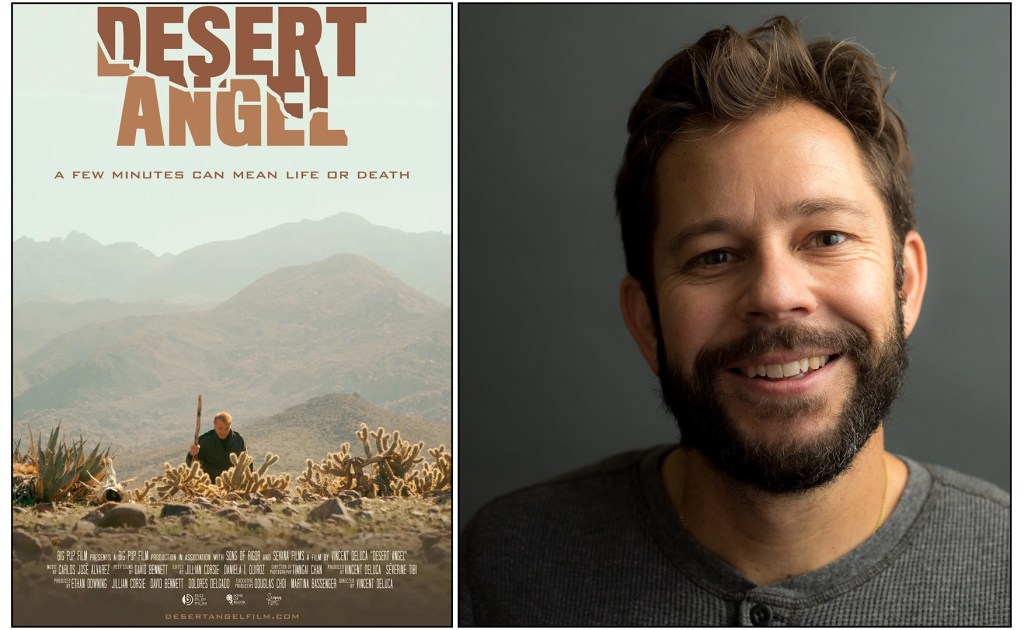

Larraenza is in his 70s, has had a double hip replacement, and is determined to keep his work going. During their five years of filming and search and rescue efforts together, DeLuca has seen Larraenza resusitate a man they found, use his mechanics background to make prosthetics for people who’ve lost a leg, and share his philosophy on serving people wherever they are in their lives in ways that benefit them. Their feature-length documentary, “Desert Angel,” has its San Diego premiere Oct. 18 at the San Diego International Film Festival. DeLuca, who’s now based in Los Angeles, talks about the film, the Larraenzas story, and his point of view on filmmaking as a shared form of storytelling. (This interview has been edited for length and clarity. For a longer version of this conversation, visit sandiegouniontribune.com/author/lisa-deaderick/.)

Q: “Desert Angel” is your feature-length documentary film centered around Rafael Larraenza, who’s spent 25 years rescuing people lost in the desert along the U.S.-Mexico border, reckoning with whether his next rescue effort could be his last. How were you introduced to Rafael and his work?

A: My wife is Cuban and I was writing a screenplay, at the time, that took place along the border. We were talking a lot about tone and language, and she encouraged me to dig deeper in my research, so I just started to do internet research for my screenplay. As I was doing that research, I came across an article that Gustavo (Solis, journalist with KPBS) had written about Rafael, and I was so moved by the piece, what I was reading and the photos that went along with the article, that I reached out to Gustavo and I just asked him, “Is this person for real? Like, they’re literally risking their life every day to save other people crossing.” We don’t show this in the film, but Rafael has this imagination that allows him to think up creative ways to enhance his searches. Like, he was making gliders that were powered by lawn mower motors so that he could literally fly over the desert to cover more ground. So, Gustavo said, “Yeah, he’s the real deal, but he’s aging. If you want to do a film on him, you need to go now,” and he put me in touch with Rafael. I called him and drove down to his bus from LA, and we met. He hugged me the first time I ever met him with such warmth and compassion, I was like, ‘This is a really special human being.’ When you do a documentary, there has to be some sort of connection for you, to the material. I wanted to know why—what makes this person tick and what I can learn from him to live a life that has more love in it? So that I can go out and treat other people the way Rafael is living his life. That’s really how it started.

Q: What was his initial response to the idea of a documentary that followed him in his work along the border?

A: He’s not about the publicity. He really doesn’t want attention. I think, at first, he and his wife, Monica, were a little bit hesitant to do it. They’d had lots of offers before and always said no, so they just wanted to see if our relationship developed into something where they felt like this was what they want to do. I was totally cool with that. I actually was kind of intrigued by just the process. I started to go out on searches with Rafael and over time, he and his wife finally said, “We’re developing into a family and we want you to be the one to tell the story.”

Q: A description from the festival characterizes Rafael as a hero to Latin American communities because of his work. Can you talk about what makes him and his work heroic to the community?

A: I spent all those years traveling with him, from California to Texas, and we would stop at places and people knew him. We’d be at random restaurants and someone would come up and be like, “You saved my cousin.” It was really meaningful and impactful to be with him when people came up and showed gratitude. You have someone like Rafael who’s willing to stand in the gap for other people. That’s what’s so impactful about him—he’s saying that these lives matter and he’s going to risk his own wellbeing to make that clear and to show love to other people. Even when he recovers remains, it’s really important because families are able to have closure and to know what happened to their loved ones. He’s just constantly out there making an effort, saying, ‘Hey, your life, the lives of your family members, they count and I’m here to honor them.’ The communities recognize that. He’s remarkable.