First, you get stuck with a crappy mom. Then she lives to be 95. That’s nearly a century of terribleness.

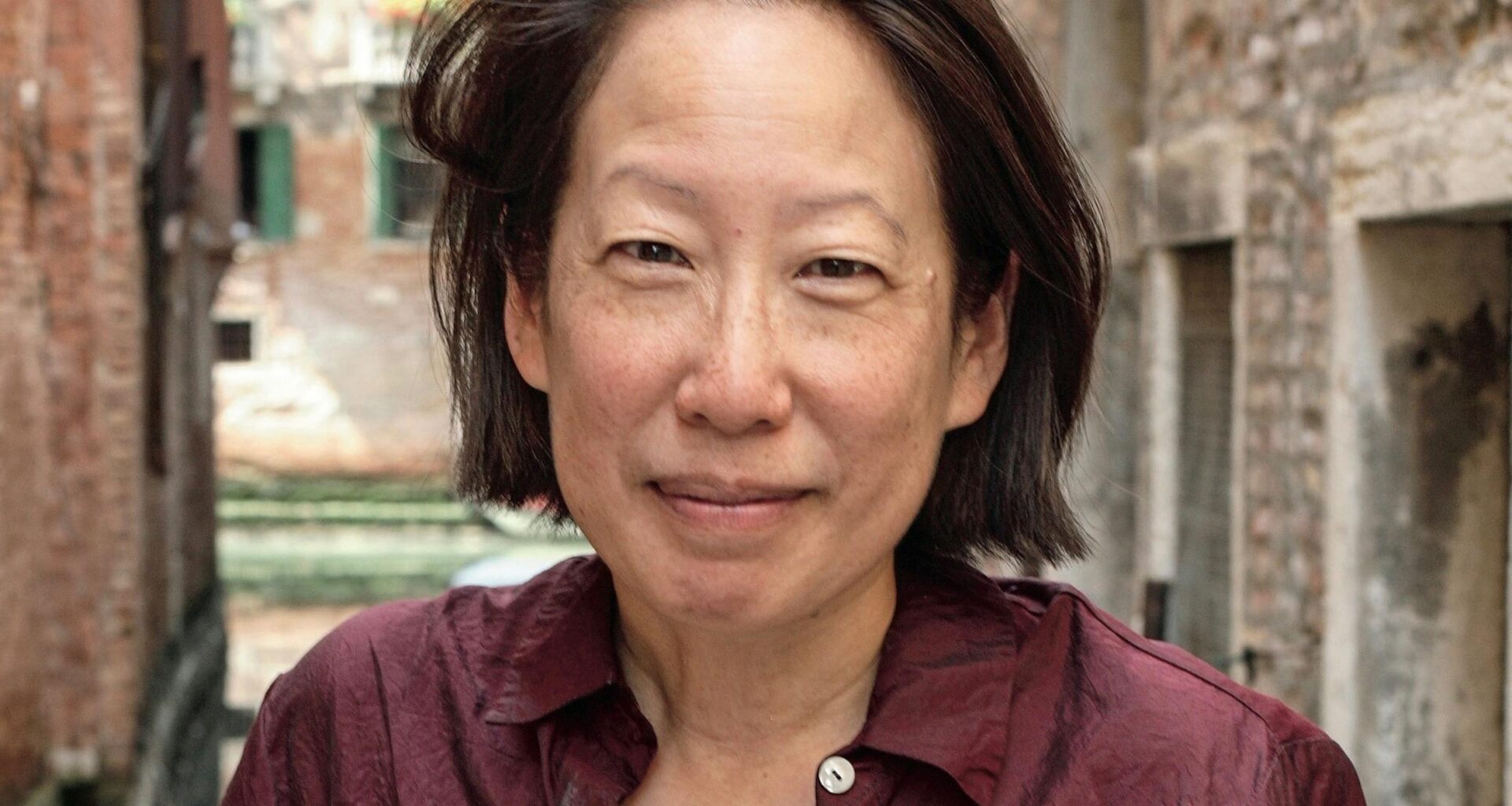

In “Bad Bad Girl” author Gish Jen’s case, “terrible” doesn’t quite cover it. Her Chinese mother, who came to the United States in 1947, was mean, abusive, unapologetic and unchanging.

Still, as Jen says in an author’s note, “I did not see how I could go on calling myself a writer had I not at least tried” to write about her mother. While one might argue that the world wasn’t clamoring for yet another Bad Mom Memoir, Jen’s captivating effort (she calls it a novel but it reads like nonfiction), brims with hard-won insights about her upbringing.

Born to wealth in Shanghai in 1924, Jen’s mother was Loo Shu-hsin, whose English name was Agnes. She grew up with servants and a beloved nursemaid. Agnes’ mother smoked chef-prepared opium. Her father was a banker.

Jen’s maternal grandmother assured Agnes that it was too bad she was born a girl, as only sons had real value. Agnes talked too much. “With a tongue like yours,” her mother said, “no one will ever marry you.” A harsh sentiment that Agnes passed along, years later, to Gish.

An excellent student at a Catholic school in China, Agnes moved to the United States to pursue a graduate degree. She never returned to her turbulent homeland, which survived Japanese occupation, devastating famine and then the Communist takeover that stripped her family of its wealth and prestige.

All of which seemed increasingly distant as Agnes moved to New York City and married a Chinese engineer, Jen Chao-pe (who received his degree from the University of Minnesota). The two moved into a tiny, roach-infested apartment. Hard-working Agnes learned to “forget everything” about China, pinch pennies, and love American baseball and TV. The couple had five children, including second-born Gish, described by her mother from the start as “a pain in the neck.”

To stop Gish’s crying, her mother slapped her, starting at age 3. “Usually she hit me on my back or arm — not so hard as to leave a bruise but hard enough,” writes the narrator, who responded by muttering “Who cares?” under her breath. Her brother, number-one son Reuben, never got hit, but faced racist taunts and regular beatings from bullies.