Gale Street Inn, an institution on the Northwest Side that closed in late June after 62 years, isn’t being remembered for its ribs. Over the last two weeks, critics of Mayor Brandon Johnson have latched onto the closing of the Jefferson Park restaurant as proof that getting rid of the tipped minimum wage is bad news for the restaurant industry.

The Tribune’s coverage of the May closure included comments from Illinois Restaurant Association CEO Sam Toia, who shared concerns about how escalating costs could lead to more closures. That led to the weekend when the Tribune’s editorial board followed with a provocative headline above a photo of the Gale Street: “Why Chicago Has a Restaurant Crisis.” The editorial warned of a future firestorm of restaurant closures. A May piece in the Sun-Times also spun a tale of impending doom. The restaurant association launched this campaign before Memorial Day, as 44th Ward Ald. Bennett Lawson introduced a proposal to repeal the ban.

All of this happened as One Fair Wage battles Springfield to ban the tipped minimum wage across the state. One Fair Wage co-founder Saru Jayaraman, whose organization has kept busy pushing similar legislation across the country, is unfazed. She tells Eater that it’s just part of a standard playbook. With federal policies taking aim at the most vulnerable when it comes to cuts to Medicaid and food stamps, Jayaraman is more focused than ever on rooting out what she views as a practice that fosters inequity in the restaurant industry. OFW has launched Solidarity Restaurants, an initiative to protect immigrant workers from ICE raids, and the group is currently working on banning the tipped minimum wage in New York.

“The [National] Restaurant Association knows that if they let it happen in New York, a lot of other states on the East Coast will follow — in the Northeast, in particular,” Jayaraman says.

In Chicago, after heated deliberations between Johnson’s camp and the restaurant lobby, the City Council agreed in 2023 to gradually rid the city of the subsidy used by restaurants over five years; in practice, this means the tipped minimum wage will increase annually by 8 percent every July through 2028. This year, the jump brings the rate for employers with four or more workers to $12.62 per hour. The standard minimum wage has also jumped to $16.60 per hour. However, critics continue to debate whether tipped workers will earn more money, arguing inflation and spiking costs are forcing customers to tip less. That’s where solutions like service fees enter the fray. Talking about service fees is a good way to start an argument online.

There’s an uneasiness for restaurant owners, particularly independent operators who face everyday operational challenges without the benefit of deep-pocketed investors. Even Thattu, heralded for embracing a no-tip and no service fee model, has brought back tipping as means to retain workers. The plight of the indepedenent restaurant is front of mind nationwide. New York mayoral candidate Zohran Mamdani has pledged to create a department dedicated in supporting “mom and pop” businesses if he’s elected to office. Waiting for licensing or responses for the right city department can crush a business.

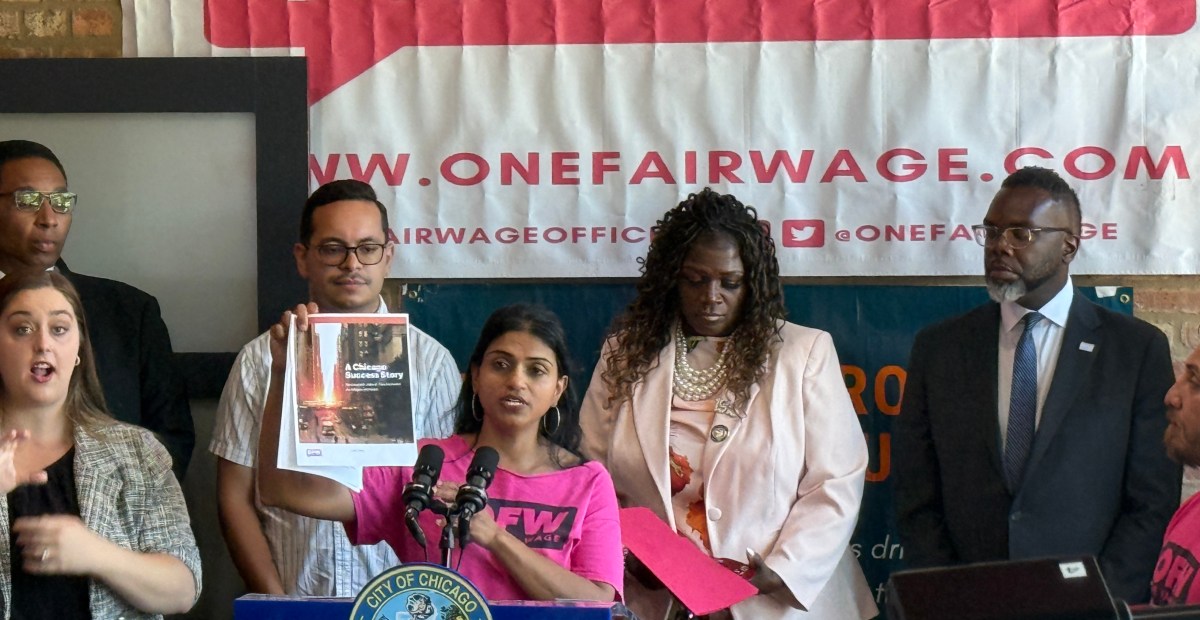

As lobbyists and lawmakers battle, restaurant workers and owners remain in limbo, confused on a variety of topics, including whether it’s legal to pool tips, sharing them with the front and back of the house. That’s a point that One Fair Wage’s Neela Caicedo-Rosario clarifies, saying sharing is permitted.

Chicagoans have been bombarded with data points as the restaurant association and One Fair Wage justify their stances. Both kept a close eye on Washington, D.C., where in 2022 voters approved a gradual elimination of the tipped minimum wage, but have since hit pause. A Washington Post editorial called the city’s move to rid the tipped minimum wage a “disaster,” much in the same way the Trib read the tea leaves in Chicago. Johnson made the tipped minimum wage a key part of his election platform, to cede power back to workers. And while his camp says that 10,000 jobs have been created since the ordinance went into effect in July 2024, the restaurant lobby claims that 5,200 jobs were lost between July 2024 and December 2024. There are also conflicting figures about the number of restaurant closings and openings, as well how much the city has lost in terms of sales tax revenue.

Last week at an appearance on the West Side in collaboration with One Fair Wage, Johnson heralded the Chicago ordinance. “There is no place for an antiquated system such as this, particularly in a great global city,” Johnson said at the press conference. “And so the One Fair Wage became a matter of justice, economic justice.”

One of Johnson’s progressive allies, 26th Ward Ald. Jesse Fuentes, played a key role in brokering a compromise between Johnson’s camp and the Illinois Restaurant Association in convincing key stakeholders to lend their voices to the discussion as the sides went back and forth two years ago.

“Some individuals are going to do the minimum wage and keep tips, some individuals are going to do the minimum wage and have a service charge, so the service charge goes to the front of the house and the back of the house,” Fuentes tells Eater. “It really depends on the model.”

With July’s arrival, the city enters the ordinance’s second year of five years of annual wage increases. Arguing about the future of Chicago’s restaurant industry is looking to be a regular summer occurrence as America enters a bizarre political time full of economic uncertainty.

“We are a diverse city with many different forms of business models,” Fuentes adds. “No restaurant is the same — it’s not a monolithic industry, right? And so that means there’s going to be different challenges depending on the business model, and we have to target one sort of restaurant at a time.”