Illustration: Tim Bouckley

This article was featured in New York’s One Great Story newsletter. Sign up here.

Four days after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, I arrived hot and resentful to a Manhattan hospital for a 32-week ultrasound accompanied by my husband. There was no particular reason for the scan, no diagnosed concern, just an impersonal risk calculation based on the fact that I was, at 38, of “advanced maternal age.”

This would be my second child, and admittedly some jadedness had set in. As a reporter, I’d also been more than a little distracted; I’d been covering the high court’s decision in Dobbs, which had almost instantly banned abortion in 13 states.

And yet. As I lay back on the exam table in the darkened room, passive and obedient, a face that had eluded us suddenly appeared on the sonogram monitor, a shockingly clear delineation: an upturned nose and pouting lips hanging open. We gazed at her in quiet surprise. “She’s looking more like a person now,” I murmured to my husband.

The ultrasound tech had been merry, cracking jokes to leaven the anxiety she presumed we might feel. Hearing me, she grew somber. She turned and spoke directly to the fetus enlarged on the screen, which is to say she literally spoke over me. “You were a person from day one,” she told the image, as if it needed reassuring.

A little too on the nose, this uninvited entrance of “pro-life” fetal-personhood ideology. It was probably the most explicit moment during my two pregnancies of being treated, by a medical provider, like an incubator rather than a person. But it wasn’t the only one.

By the time I got pregnant on purpose, in 2019, I thought I understood quite a lot about reproductive health care. Over more than a decade, I’d spent countless hours with abortion providers — people I considered heroes, who’d risked their careers and even safety to offer care in increasingly hostile environments, and I’d talked to dozens of abortion patients. I’d seen and heard how these doctors, nurses, and counselors treated each person who walked through their doors with compassion and dignity, no matter their circumstances. I’d watched the meticulous attention they paid to informed consent, making sure their patients understood what was happening and their options. It’s not that there weren’t abrasive or indifferent providers, or ones who fit the anti-abortion stereotype of transactional opportunists. But the vast majority saw their work as a calling. Performing abortions isn’t work anyone undertakes casually; people choose it under sometimes life-threatening scrutiny.

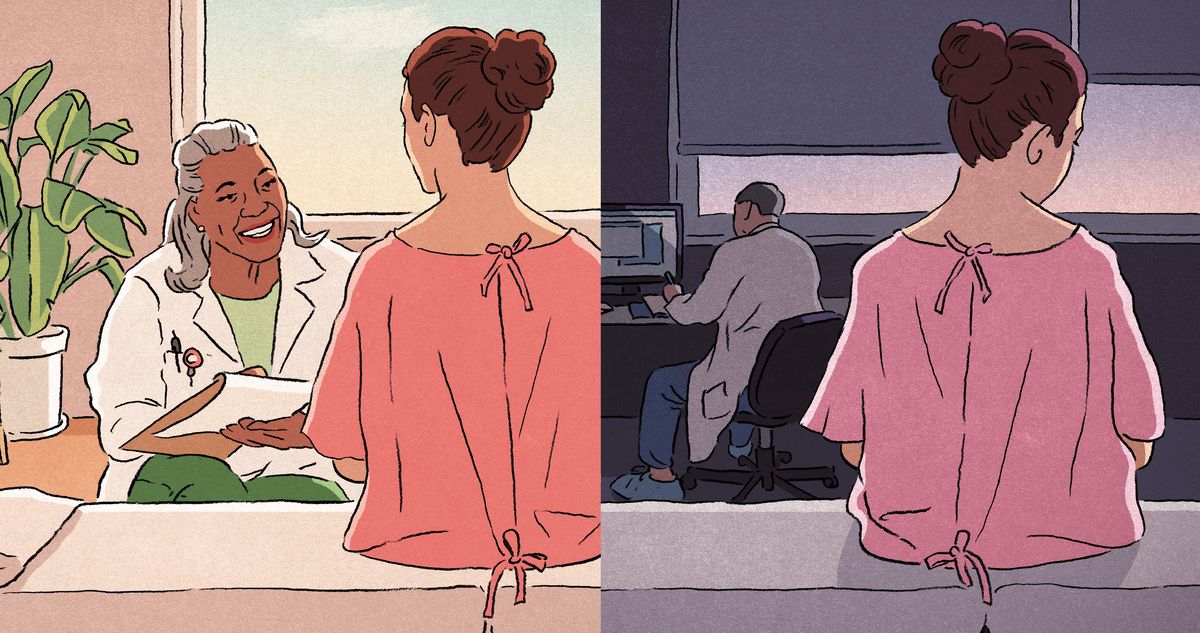

What I didn’t understand, however, was how rare this standard of care — the high degree of empathy and the ever-present recognition of patient autonomy — was outside the heavily secured walls of abortion clinics. During my first pregnancy, despite living in supposedly progressive New York City, having plenty of choice of providers due to good insurance, and hunting down a practice that promised to be both “woman-centric” and evidence-based, I found myself navigating a system that again and again treated me as secondary to the pregnancy I was carrying.

At the same time, I knew from both life and work that so much could go wrong in a pregnancy, and complaining about what amounted to microaggressions felt churlish. So what if the doctor who attended my first delivery bullied me into pushing before I was ready, and on my back — the position most convenient for her and most painful for me — and then afterward, when I asked about tearing, snapped that if I were in the “third world,” the staff wouldn’t even be stitching me up. Or that I later found out from another provider that my doctor had lied to me about how badly my body had torn. Wasn’t bringing home a healthy baby all that mattered?

But I couldn’t simply put aside everything I knew about abortion care. Why was my prenatal and birth treatment so drastically different? In the years following Dobbs, my work kept reaffirming the distinction: People told me, again and again, that their most respectful, patient-centered reproductive health care had come not from the obstetricians, hospital staff, or even midwives who’d tended to them during wanted pregnancies but from abortion providers. Why couldn’t women be treated just as well during the rest of pregnancy?

A little over a year after my post-Dobbs ultrasound, in September 2023, I spread a blanket on the patchy grass of a local park and held my damp-haired second baby on my lap. A few loosely connected families had gathered; our kids were about to start public preschool together. New York smelled mustily of late summer, lingering into the fall’s new beginnings.

A mother I knew asked me about the subject of my book in progress, and I struggled to answer. “The way you’re treated when you’re pregnant …” I said, and paused, searching for a word that would be honest without saying too much in front of people I’d just met. “Like you’re a child.” I shouldn’t have worried about being understood.

“Like an animal,” another mother replied instantly.

“Like a child-animal,” said another, an artist named Maggie, vehemently.

The sudden rawness of the moment stayed with me. It was, for the most part, a group of people with education and access, people who had options, who were used to asking for something better, whatever better looked like to them, and even getting it. If some of the luckiest, best-prepared women in America felt a shudder of recognition at the phrase “child-animal” when recalling childbirth — a process our culture supposedly holds sacred — what hope was there for everyone else?

Maggie, I soon learned, had moved to New York for love a few years earlier. Coming from Canada, the rapaciousness of American health care — the expense; the cold, unfair distribution of resources — literally brought her to tears. When she got pregnant, in the fall of 2018, her first few medical appointments were rushed and rote and left her longing for someone to take care of her as a person, not a uterus. She and her husband, Matt, read Spiritual Midwifery, the 1976 counterculture classic by self-taught midwife Ina May Gaskin, and were inspired to find a birth center — a middle ground between a home birth and a hospital, staffed by midwives, which Maggie hoped would ensure personalized attention.

When she went into labor, though, the birth center seemed more like a less-equipped hospital, and the midwife appeared to be checked out. Maggie didn’t feel supported; she felt tense and lonely. Around 20 hours in, the baby was deemed stuck and she was transferred in an ambulance to a nearby hospital. Though it hadn’t been what she’d hoped for, Maggie was relieved when doctors called for a C-section. But the anesthesiologist shouted at her and ignored her, giving her additional fentanyl that she’d expressly declined. When she next awoke, she couldn’t move and found that her breathing was being controlled: She’d been intubated and was in intensive care. A hospital staffer told her that her husband’s screams for help had saved her life; her surgeon had failed to notice that he’d improperly sewn an incision and she’d bled internally. Her baby was fine, but Maggie had needed a full blood transfusion.

Maggie’s level of injury was extraordinary, but the lack of support and bullying she’d experienced along the way was not. Survey data analyzed by the CDC in 2023 found that 20 percent of women reported that they’d been mistreated at their most recent birth — for Black women, the number jumped to 30 percent. The most common forms of mistreatment were being ignored when asking for help, being shouted at, being threatened that treatment would be withheld, and being forced to accept unwanted treatment. Some research shows that seeing a midwife, as Maggie initially did, correlates with being treated better, but it’s not a panacea.

Two years later, Maggie still wasn’t getting her period regularly and was receiving hormonal treatments; her blood loss during childbirth had caused lasting damage. She didn’t think she could even ovulate, but in the fall she learned she was nine or ten weeks pregnant. Fragile and uncertain how her treatments would affect a pregnancy, she knew she couldn’t carry to term. She also knew she was lucky she lived in New York. It was 2021, and Texas had just banned abortion at six weeks. Outside the Planned Parenthood in Manhattan, Maggie pushed past a protester who tried to hand her a pamphlet offering a free stroller and car seat.

Inside, a counselor, following protocol, asked her husband to leave the room so the clinic could be sure Maggie wasn’t being coerced. She assured the counselor she wasn’t. But the counselor had noticed Maggie’s anxiety and asked if she was okay. Maggie burst into tears and confessed that she feared the procedure would kill her, as childbirth almost had.

The counselor listened. She walked Maggie through all the potential risks but also statistics showing that abortion is much safer than giving birth. The most commonly cited data says that abortion is 14 times safer; a more recent analysis suggests that terminating a pregnancy is at least 30 times safer than staying pregnant.

Maggie felt better but was still afraid of the anesthesia, of waking up immobilized as she had in the ICU. The clinic said she could decide how sedated she wanted to be. When she woke up this time, rather than feeling terror she felt pure gratitude. It wasn’t just the drugs. The abortion had been, she said, “the best prenatal care I’ve had.”

NYU nursing professor and midwife P. Mimi Bhatt studies how midwifery in hospitals can save lives and combat inequities. When I asked her how she chose her path, I wasn’t expecting her to reply that it was because she’d had an abortion. Her father was a doctor, but her early health-care experiences, she said, were “cursory and mechanical.” As a college student, she got pregnant and, when she went to an abortion clinic, was treated by a midwife and experienced something quite different.

“I don’t remember any of the physical and material aspects of the care,” she told me, “but I remember how the provider made me feel: very centered, very seen. That this person wanted to take care of me — and not just what was happening in my uterus, but my mental and emotional struggle.”

That experience sent Bhatt to the library, then to midwifery school, and eventually to a career dedicated to providing the kind of comprehensive reproductive care she’d experienced that day. “Midwives are the original abortion-care providers,” she told me. “This is part of our legacy, to provide this kind of whole-person care.”

That legacy has been maintained outside mainstream medicine. In the U.S., in the latter half of the 19th century, midwives — who were willing to help women end their pregnancies (or “restore their menses”) — were pushed to the margins of reproductive medicine by white male doctors looking to establish legitimacy and dominate the field. Midwives were not powerful people — many were immigrants or Black women — and doctors claimed to offer safer, more technologically advanced birth.

At mid-century, abortion was not yet a crime. But birthrates were declining — by 1900 the average number of children born to American women would wane from seven to three or four — and physicians were able to capitalize on nativist anxieties. Dr. Horatio R. Storer, an influential Harvard professor, openly worried that the children of “aliens” — immigrants — might supplant those of “our women,” and took it upon himself to offer a new definition of pregnancy, citing advanced science, “Physicians have now arrived at the unanimous opinion, that the foetus in utero is alive from the very moment of conception,” he declared in 1867. For the next hundred years, the AMA would officially oppose abortion. By 1880, every state had enacted abortion restrictions of some kind, and by 1910 all had made the procedure entirely illegal.

The new medical establishment was deeply paternalistic. “Wise women choose their doctors and trust them,” S. Weir Mitchell, the inventor of the “rest cure” for female hysteria, wrote: “The wisest ask the fewest questions. The terrible patients are nervous women with long memories, who question much where answers are difficult.” Doctors, who in that century were still bloodletting and using leeches, persuaded women that safer birth came from surrendering their authority.

By the middle of the 20th century, a later generation of doctors, spooked by the septic-abortion patients who showed up begging for help after taking matters into their own hands, began to leverage their power to reverse some of the damage, lobbying for women to have contraception access and reforming the abortion bans doctors had previously fought for. In 1965, the Supreme Court ruled that states couldn’t ban contraception for married people, and eight years later, with Roe v. Wade, the court struck down all those 19th-century abortion bans. Abortion was suddenly legal throughout the U.S.

Roe’s effect was revolutionary, but its reasoning, notably crafted by moderate Republicans with deep respect for the Establishment, was not. “Roe v. Wade was as much about a doctor’s right to practice his profession as he sees fit,” Ruth Bader Ginsburg told me in 2015, as it was about the right of a woman to control her body. “And the image was the doctor and a little woman standing together. We never saw the woman alone.”

In the years since the ruling, abortion care has remained at the fringes of medicine, held there by the force of the law as well as vigilante violence. This has allowed the practice to stay free of some of the field’s more paternalistic impulses. Providers have had to earn their patients’ trust rather than command it, as they’ve had to justify their existence before the government and a hostile opposition. At their best, abortion providers have maintained an understanding that predates modern medicine, one that much of the reproductive field has forgotten: Pregnancy is not just a medical condition but a profound life experience touching on a person’s deepest values, dreams, and fears. As Bhatt explained to me, midwives have long understood this and were historically “the central hub” of one’s natal care, tasked with “the psychological, social, and cultural implications of anything related to pregnancy.” “Abortion starts with a pregnancy,” she said. “Loss starts with a pregnancy. All the issues around pregnancy stem from this baseline foundational understanding that care is more than just the physical and mechanical.”

The practice of medicine has come a long way since white-coated patriarchs took over the field, and a majority of obstetricians are now female, but patients still deserve far better. Returning respect and real empathy to prenatal, birth, and postpartum medicine sounds almost utopian at this bleak moment — legal abortion practice has disappeared from a dozen states. But crises can be clarifying. All reproductive healthcare providers should learn from those who perform abortions: The pregnant person is the protagonist of their own story, not a supporting character.

Copyright © 2025 by Irin Carmon. Adapted from the forthcoming book Unbearable by Irin Carmon, published by One Signal Publishers, an Imprint of Simon & Schuster, Inc. Printed by permission.

One Great Story: A Nightly Newsletter for the Best of New York

The one story you shouldn’t miss today, selected by New York’s editors.

Vox Media, LLC Terms and Privacy Notice

Related