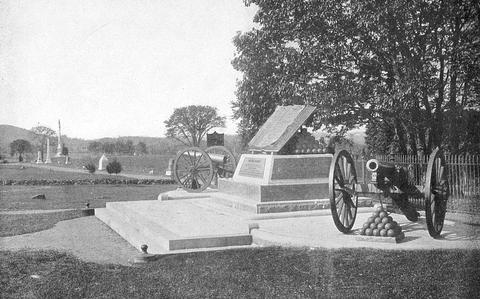

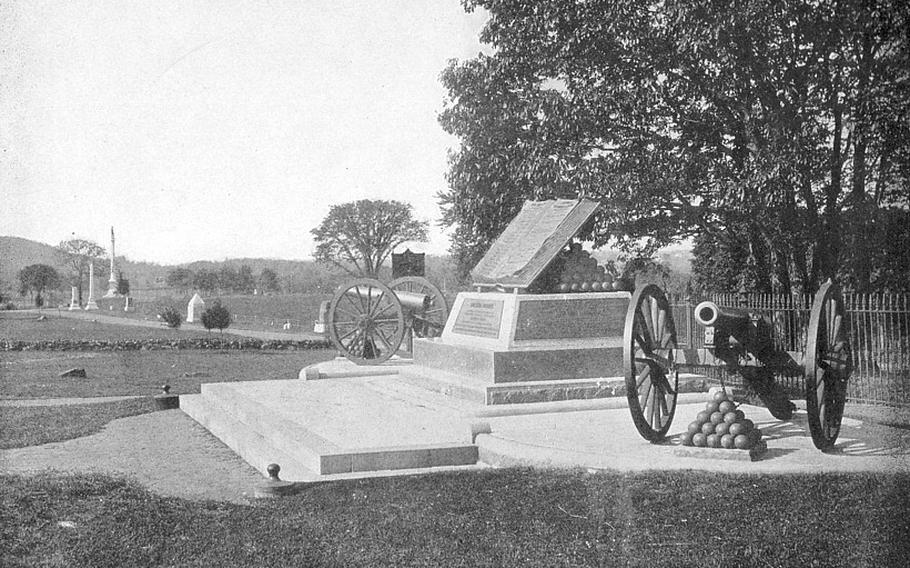

The High Water Mark and other monuments on Cemetery Ridge, Gettysburg National Military Park, Pa., photographed in 1910. (National Park Service)

By one estimate, more than 65,000 books were published about the American Civil War in the first 130 years following its conclusion in April 1865, and they keep coming.

One new volume this year focuses just on the weather during the three-day battle in July 1863, another dissects — again — the action on the third day.

A third book this year is a reissue of a classic study in command — “They Met at Gettysburg” — for the 70th anniversary of its publication in 1956 by Stackpole Books, whose founder, Edward Stackpole, wrote the book along with several others on the Civil War.

Stackpole, a real-life general from Harrisburg, Pa., served in World Wars I and II, tells his version of Gettysburg from a command point of view.

“They” in this context are the generals on both sides. The view is primarily from horseback, rather than over a fence rail.

The book still holds up as a basic overview of the primary events and decisions that led up to the battle, starting outside Fredericksburg, Va., in late June 1863, to Lee’s retreat beyond the Potomac River in early July. Stackpole turns a soldier’s eye and uncompromising judgment on the leaders who sent more than 5,000 to their deaths.

Atop that pantheon is Robert E. Lee, whom Stackpole clearly admires as a figure of integrity and leadership ability. Lee is, mostly, an aggressive general willing to accept risk for big results. He also represents, in the author’s estimation, lost virtue.

For nearly a century, military historians wrote panegyrics to the Confederacy laced with undertones of regret that the rebels had been vanquished. Stackpole does not fit in that category, but “They Met at Gettysburg” does indulge in a version of history exploited by Lost Cause writers of the losing side, Gens. John B. Gordon and Jubal Early among them. Their premise holds that the South, the better warriors, was overpowered by a better supplied and a more populous North. Lest the argument fail, the narrative must show Lee as a nearly infallible genius of noble character.

“They Met at Gettysburg,” first published in 1956, is back in paperback for its 70th anniversary. (The Globe Pequot Publishing Group)

The primary tenets of Lost Cause dogma start with regret that Stonewall Jackson had died before Gettysburg, for surely his presence would have been a decisive factor; that cavalry commander J.E.B. Stuart failed Lee by going on an indulgent ride around the Union Army to restore his reputation; and Richard Ewell failed to press the Confederate attack up Cemetery Hill on the evening of the first day as the routed Union Army was still collecting itself.

But the principal villain is Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, Lee’s right arm. Longstreet disagreed with Lee’s plans for invading Pennsylvania and the doomed attack on Maj. Gen. George Meade’s Army of the Potomac, and counseled making an end-around on Meade and setting up a defensive line. Longstreet admitted this after the war.

The extent to which he balked at Lee’s orders based on “childish” intransigence, engaged in “consciously dilatory tactics” throughout the battle or peevishly delayed troop movements at crucial times, as Stackpole writes, is questioned by more recent historians.

Stackpole ultimately faults Lee, the commander, for the rebels’ loss at Gettysburg, for his failure to render clear, decisive orders and ensure his corps commanders worked in unison to hold and then hammer the Union Army.

“They Met at Gettysburg” still reads like a cavalry trooper rushing to the skirmish line, with a hard-eyed soldier’s take on America’s bloodiest conflict.