On a Saturday afternoon in 1970 in St. Louis, Missouri, an entrepreneur named Morton Meyer put his young son Danny to work as he wrote newsletters to his clients. Danny was 12 years-old and tasked with stuffing those newsletters into envelopes, licking them closed, and stamping them to be mailed. It’s a memory that bubbled up when he opened his first restaurant, Union Square Cafe, on October 21, 1985, when he was 27 years old.

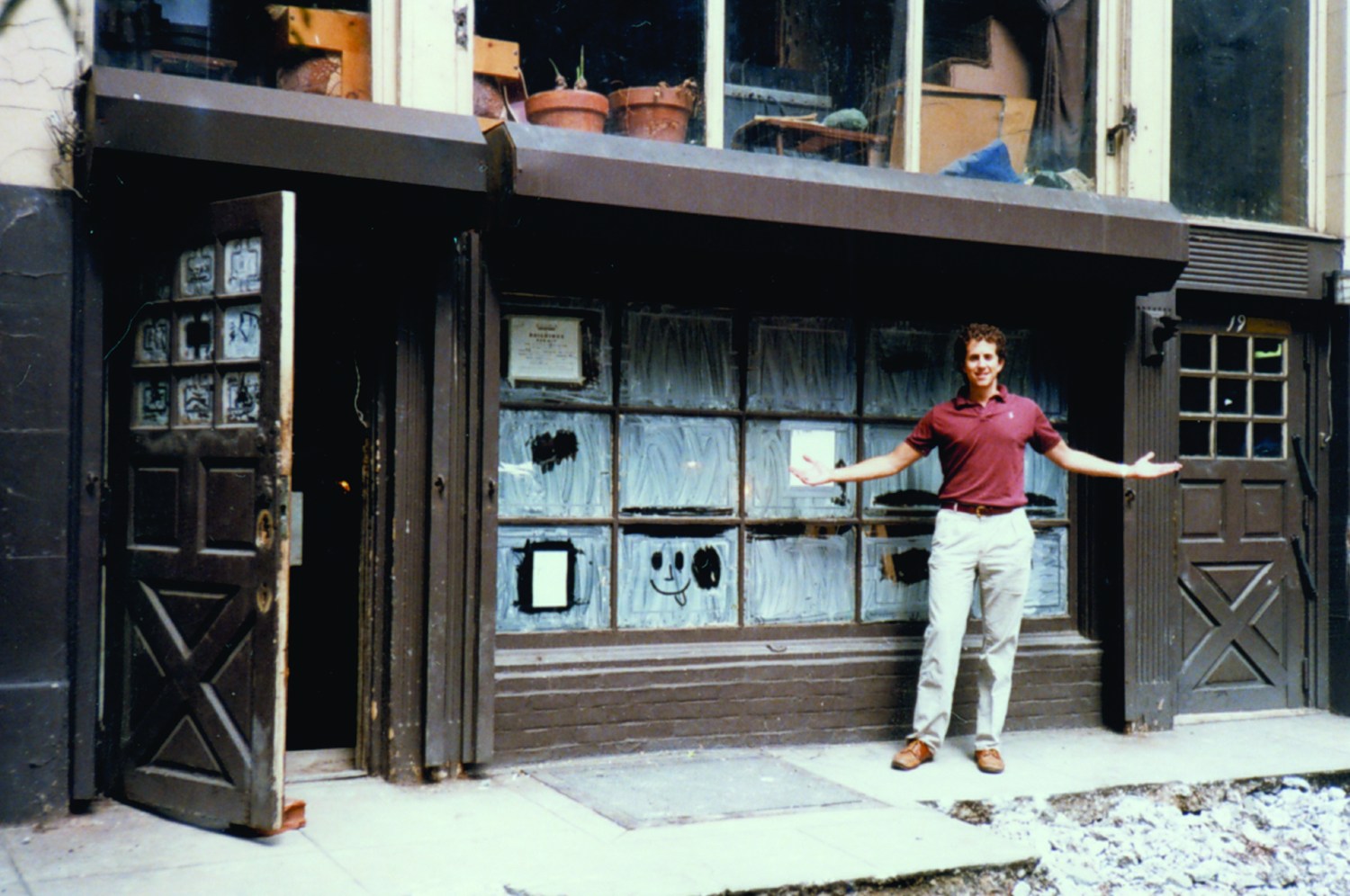

Danny Meyer in front of Brownie’s before it became Union Square Cafe. Union Square Cafe

Nathan Rawlinson

Earlier this month, Meyer celebrated its 40th anniversary; today Union Square Cafe is still a New York City icon. It’s one of nine restaurants outside the Shake Shack empire under Meyer’s umbrella, a group that includes Gramercy Tavern, the View, Daily Provisions, Ci Siamo, Manhatta, The Modern, Porchlight, and soon its first Detroit property, Hudson’s Detroit, set to open in 2026. (His group also launched Tabla, Blue Smoke, and Eleven Madison Park).

In October 1988, a couple years after the opening, Meyer sat down at his electric Smith-Corona typewriter in his basement office of the original East 16th Street location, where upstairs chef Michael Romano cooked tuna burgers and Bibb salads, and typed his first newsletter. It was the beginning of a monthly ritual, after which he’d mail them to 100,000 people whose addresses he collected through written comment cards diners would fill out at their tables after eating.

Inside Union Square Cafe today. Peter Garritano

Max Flatow

Meyer found the old newsletters from the 1980s to 2009 (available here) in his mother’s home after she died. “She had them all kept in this big bracket. It was like hitting the jackpot,” he said. The collection shows the world of dining and the city’s milestones from the smoking ban to the fall of the Twin Towers.

In those newsletters, he included invitations to events like Morning Market Meetings (recently revived) and wine dinners. In an analog version of Resy’s “notify” feature, those who wanted to attend had to fill out a form and mail it back to enter into a lottery for seats.

The newsletters ranged from proud to self-depricating in tone. In the summer 1989 newsletter, for instance, he wrote about being reviewed by every one of the area’s major restaurant critics, including the Bergen Record, Newsday where Molly O’Neil was the critic, and the New York Times. Following the Times’s two-star Bryan Miller’s review, Meyer wrote, “Each of us at Union Square Cafe intends to keep working hard to be your favorite restaurant and we’ll always keep looking for ways to improve our act.”

He also kept a sense of humor, such as the time he recalled a lunch service when the dining room flooded, which he called the Greatest Anguish and Embarrassment” of 1990. “We scrambled for buckets and then ran upstairs, where we found our plumber struggling to shut off an out of control gushing water pipe, as four different parties arrived for lunch announcing names that were not on the books.” The plumber involved with the waterfall had apparently taken it upon himself that morning “to answer our telephone and to take the reservations for us, without writing any of the names down!”

Danny Meyer with Michael Romano on his last day of service. Daniel Krieger

Francesco Sapienza

The newsletters also tracked the culinary zeitgeist. One from 1990 addressed protecting the dolphins through buying sustainably caught tuna, while another a year later focused on low cholesterol and dairy-free sauces. Some newsletters were like an analog version of Page Six in which Meyer shouts out star appearances like Matthew Broderick, JFK Jr, Kevin Kline, and Tom Brokaw.

Meyer didn’t shy away from spotlighting conflict, either. Under “The Best Decision of the Year,” in 1991, Meyer wrote about implementing a smoking ban in all three of Union Square Cafe’s dining rooms, and included excerpts of regulars who disagreed. “It’s unfortunate that you’re turning your restaurant into a health club,” he quoted one. Meyer looked at the positive. “We have gotten better acquainted with some of our regulars who smoke as they often keep us company at the bar while taking a puff between courses.” (Smoking was not banned in NYC restaurants until 2002.)

One of the most solemn newsletters was printed after September 11, 2001.“These have been sad uncertain times in New York, and it has been difficult for any of us to find appropriate words for all that has occurred,” he wrote. “In the hours following the attack it was quite natural to question the significance of one’s life role or professions. I know I asked myself, after all this, who really cares about restaurants?”

Quickly though, I answered my own doubts. In their ability to nourish and nurture, restaurants – as a healing agent – are more relevant than ever.” Decades later, his words still ring true.

Liz Lignon