Roughly 2.75 million years ago, early humans of Kenya’s Turkana Basin lived in a harsh and unpredictable world. The landscape repeatedly changed with periods of drought, shifting rivers, and extensive fires. Yet despite these upheavals, a newly published study in Nature Communications shows that these ancient toolmakers maintained a remarkably stable technological tradition for nearly 300,000 years.

Replica of an Oldowan stone tool from Dmanisi, Georgia (right), compared with a later Acheulean tool (left). Credit: Gerbil / CC BY-SA 3.0

Replica of an Oldowan stone tool from Dmanisi, Georgia (right), compared with a later Acheulean tool (left). Credit: Gerbil / CC BY-SA 3.0

At the heart of this discovery is the Namorotukunan site, situated in the Koobi Fora Formation and preserving one of the oldest and most continuous records of Oldowan stone tool use ever found. The international research team, which included scientists from George Washington University, the Max Planck Institute, and Utrecht University, identified three archaeological layers that date from between 2.75 and 2.44 million years ago. In all, they represent a long, continuous record of early humans creating sharp-edged stone tools with precision and consistency.

The Oldowan tools were simple, multi-purpose implements — in effect, the first technological advancement in human history. They were used to cut meat, crack bones, and process plants. What makes Namorotukunan stand out is the remarkable persistence of this tradition. As fires swept across the grasslands and the environment became increasingly arid, early hominins continued to make and use the same kinds of tools in the same way.

Advanced dating methods undertaken by the team, including analyses of volcanic ash layers, magnetic signals in ancient sediments, and geochemical studies of surrounding rocks, established the site’s timeline. Such techniques revealed a clear picture of a changing environment and a community of toolmakers who adapted to it without altering their core technological approach.

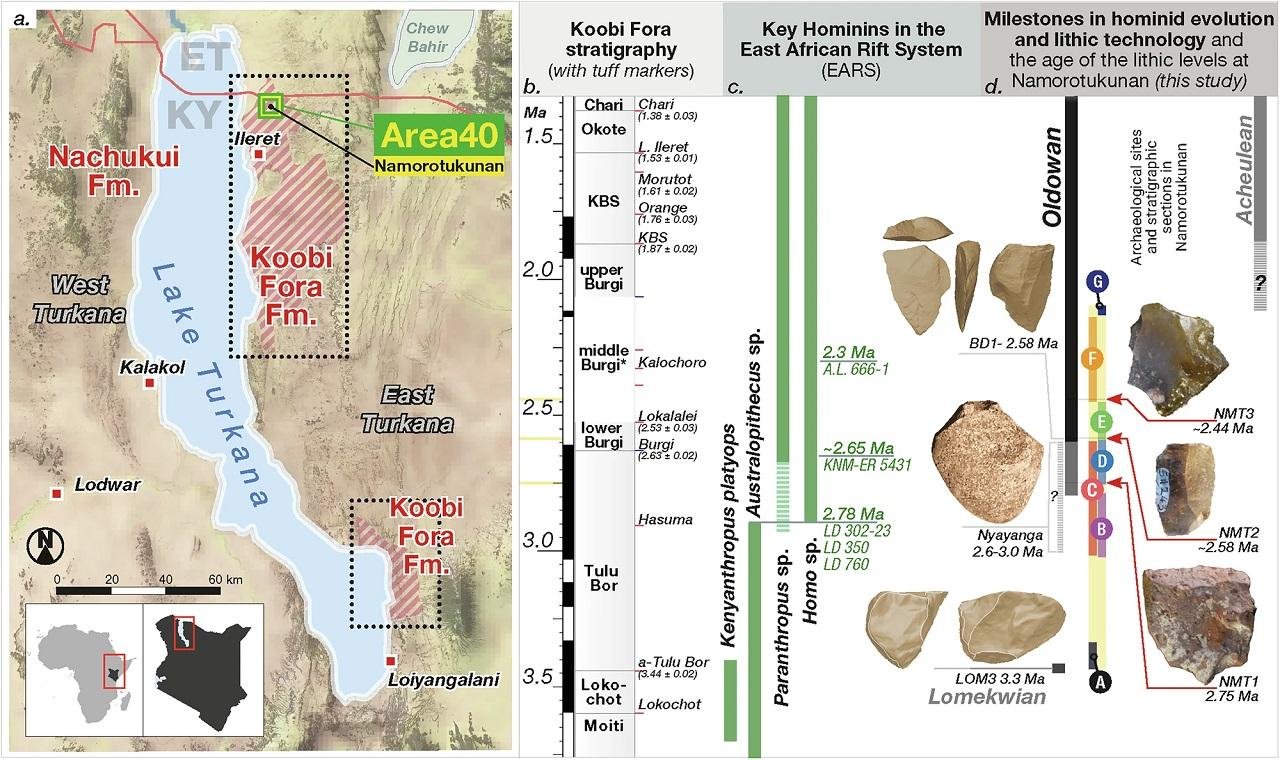

Map of Turkana Basin with the Namorotukunan Archeological Site and timeline of currently known events in the Plio-Pleistocene. Credit: D.R. Braun et al., Nat Commun (2025)

Map of Turkana Basin with the Namorotukunan Archeological Site and timeline of currently known events in the Plio-Pleistocene. Credit: D.R. Braun et al., Nat Commun (2025)

The findings from the study indicate that these early humans had not only technical skills but also cultural resilience. The persistence of toolmaking techniques across hundreds of thousands of years implies knowledge transmission between generations and, therefore, one of the earliest examples of technological continuity in the human record.

Evidence from the site also links stone tools to changing diets. Fossil bones bearing cut marks reveal that meat was increasingly important as vegetation shifted from wetlands to dry grasslands. The ability to process animal resources efficiently may have offered a crucial survival advantage during times of environmental instability.

By placing these findings into a broader evolutionary context, the researchers make the case that the Namorotukunan site represents a turning point in the study of early human behavior. Rather than passively reacting to environmental stress, these toolmakers took an active role, using technology to stabilize their way of life. The endurance of their craftsmanship speaks to how technology—well before the emergence of modern humans—had become a fundamental tool for survival and adaptation.

In many ways, Namorotukunan opens a window onto the dawn of a truly defining human trait: the ability to rely on learned, shared knowledge to navigate a changing world. The continuity of Oldowan technology over 300,000 years speaks volumes about more than skill: it tells of a deep-rooted human propensity to preserve and improve on ideas that work.

These findings not only extend the timeline of Oldowan toolmaking known in East Africa but also highlight the powerful link between culture, environment, and survival.

More information: Braun, D.R., Palcu Rolier, D.V., Advokaat, E.L. et al. (2025). Early Oldowan technology thrived during Pliocene environmental change in the Turkana Basin, Kenya. Nat Commun 16, 9401. doi:10.1038/s41467-025-64244-x